The thirteen braids that escaped an Israeli prison

I was almost 21 years old and in my final year of an undergraduate programme in photography at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in occupied Jerusalem when several stabbing attacks took place following the murder of Muhannad al-Halabi by Israeli police in early October 2015 in the Old City.

It became my mission to find my own way to resist this oppression and liberate my conscience rather than passively observe the sacrifices of my people

The stabbing attacks were the result of the escalation in Israeli settler and police violence against Palestinians, which reached a turning point when Jewish settlers burned down the Dawabsheh family home in the middle of the night in the West Bank village of Duma, murdering a young couple, Saad and Riham, along with their 18-month-old son Ali, and gravely injuring their four-year-old son Ahmed.

That same year, East Jerusalem witnessed daily violence against young Palestinian men by Israeli occupation forces, from humiliating body searches to violent arrests based on mere "suspicion" and extrajudicial killings of suspects. Palestinian worshippers who happened to be at the scene were also subjected to the indiscriminate firing of live ammunition, tear gas canisters, and rubber-coated bullets, to the extent that the Damascus Gate became known as the "Gate of the Martyrs".

Neither women nor young girls were exempt from this brutality. Fatima Hajiji, who was 16 years old, was killed by Israeli occupation forces for allegedly attempting to stab an occupation officer in 2017, and 49-year-old Siham Nimr, was summarily executed in the same spot at the Damascus Gate.

Israeli prisons have been full of Palestinians since that period.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

After finishing my studies, I travelled to Paris to present my photography project and begin planning new ones. On the banks of the Seine, I worked in a studio in the International City of the Arts, which opened to assist Palestinian artists thanks to the efforts of the renowned poet Mahmoud Darwish and literary critic Edward Said.

Attack on women’s bodies

I left the Holy City for a city that treats women's bodies as “holy” in its own way, as if they were temples for worship. As I got closer to women who walked red carpets in Paris, it became increasingly difficult to distance myself from the bodies of wounded and dying women on the asphalt in the streets of Jerusalem.

How could I spend time in Galeries Lafayette, or wander around Montmartre, or visit the Louvre, while Palestinian women and girls back home were hurt or locked away behind bars, making kunafa using the only ingredients available to them – dry bread – in an attempt to sweeten an otherwise horrific experience of suffering at the hands of occupiers on a daily basis?

The news and scenes of violence back home in Palestine continued to haunt me. I could not plan my own future or pursue an advanced degree when other young Palestinian women and girls in Israeli prisons struggled to obtain a high school diploma in the face of ongoing torture and abuse.

It became my mission to find my own way to resist this oppression and liberate my conscience rather than passively observe the sacrifices of my people.

When I returned to Palestine, I began visiting the homes of women prisoners and learning their stories from their families. I also visited those who had been recently released from prison. Lina al-Jarbouni, who was from the village of Arraba in the Lower Galilee, was released in April 2017 after serving more than 15 years in prison. She was known as the "Dean of the Women Palestinian Prisoners".

I asked her about the prison conditions, especially for teenage girls who were known as "Zahrat", or flowers, in a monthly magazine the prisoners published. I asked how she helped the young women and girls manage their affairs, take care of them, and ease their suffering as best as she could.

An act of solidarity

While chatting about her experiences in prison, Lina asked to be excused and then returned with a pile of old newspapers hiding something inside of them. She asked me to open them, which I did readily.

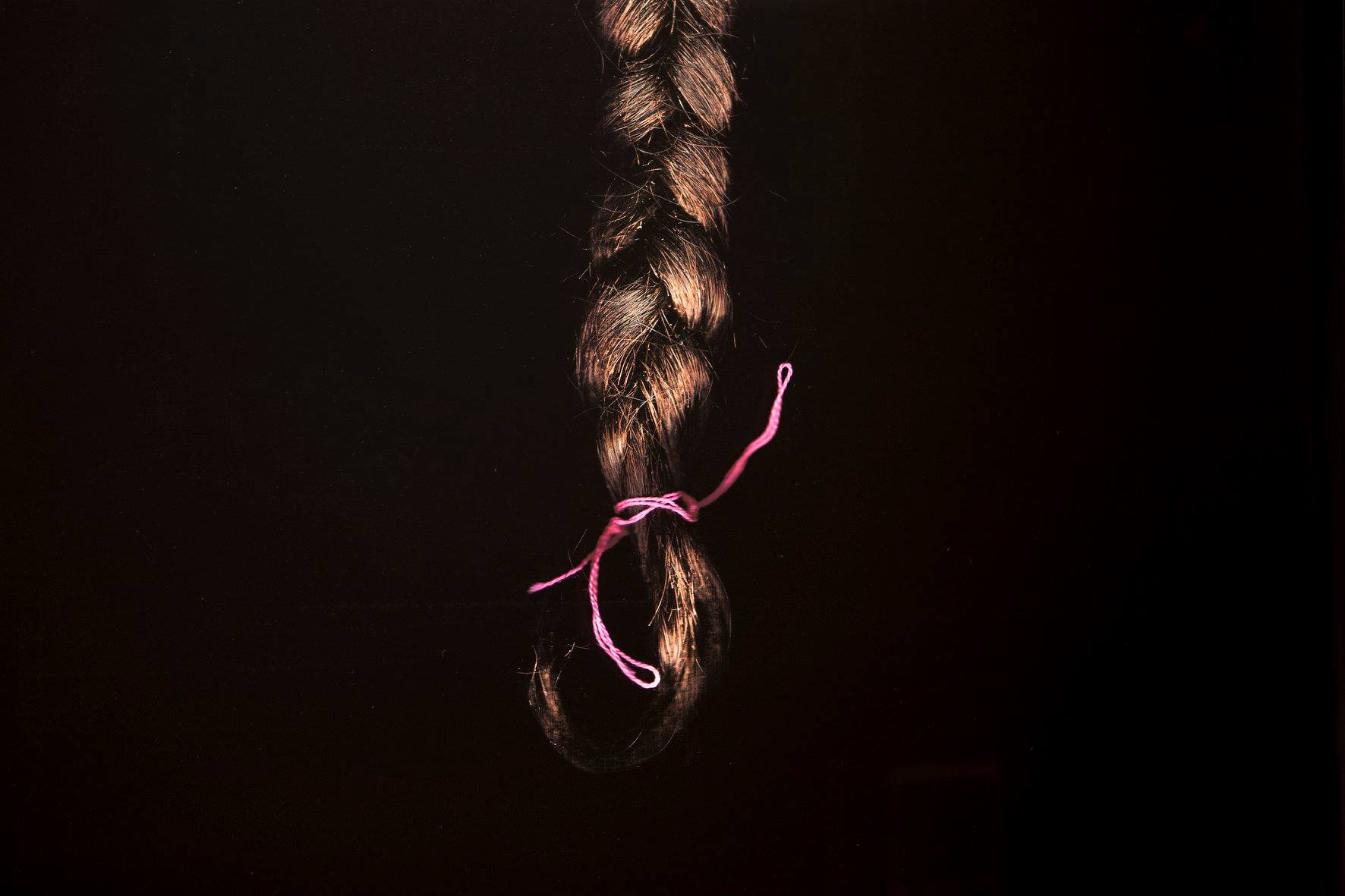

There I found 13 hair braids, each tied with a pink silk thread. Chills ran through my body and I cried without having yet understood the full story of these braids wrapped in Hebrew newspapers.

Lina was able to identify each one without any markers: "This one is from Marah Bakir; this one is from Nourhan Awad; and that one is from Tasneem Halabi." She had cut the braids herself.

It all began on a typical day when the girls in the unit were awaiting the broadcast of "The Prisoners", a programme on a Palestinian radio station whose signal managed to penetrate the walls of Hasharon prison.

Aside from letters that sometimes took months to arrive, if at all, and occasional parental visits, the radio show was the only way to communicate with the outside world, as the prisoners listened to recorded messages from their families and friends.

The radio show also featured ads, including one in particular that stood out to the girls and young women in prison. It was a breast cancer awareness commercial that deeply touched the girls who were eager to contribute in any way they could. Without hesitation, they decided to donate their hair to cancer patients, cutting braids they tied with DMC threads they used for making Palestinian embroidery.

With no guarantee that the braids would reach the campaign’s organisers, as prisoners are not allowed to send anything out of prison, Lina’s impending freedom meant that she could take the braids with her as personal belongings, and she promised to try her best to donate them.

Lina then wrapped the braids back up in the newspaper and handed them to me, trusting that I would find something to do with them. I reluctantly accepted them and kept them sealed for months, opening them up from time to time to check on their condition, still unsure of how to properly present them to the world through art.

Art, life, and resistance

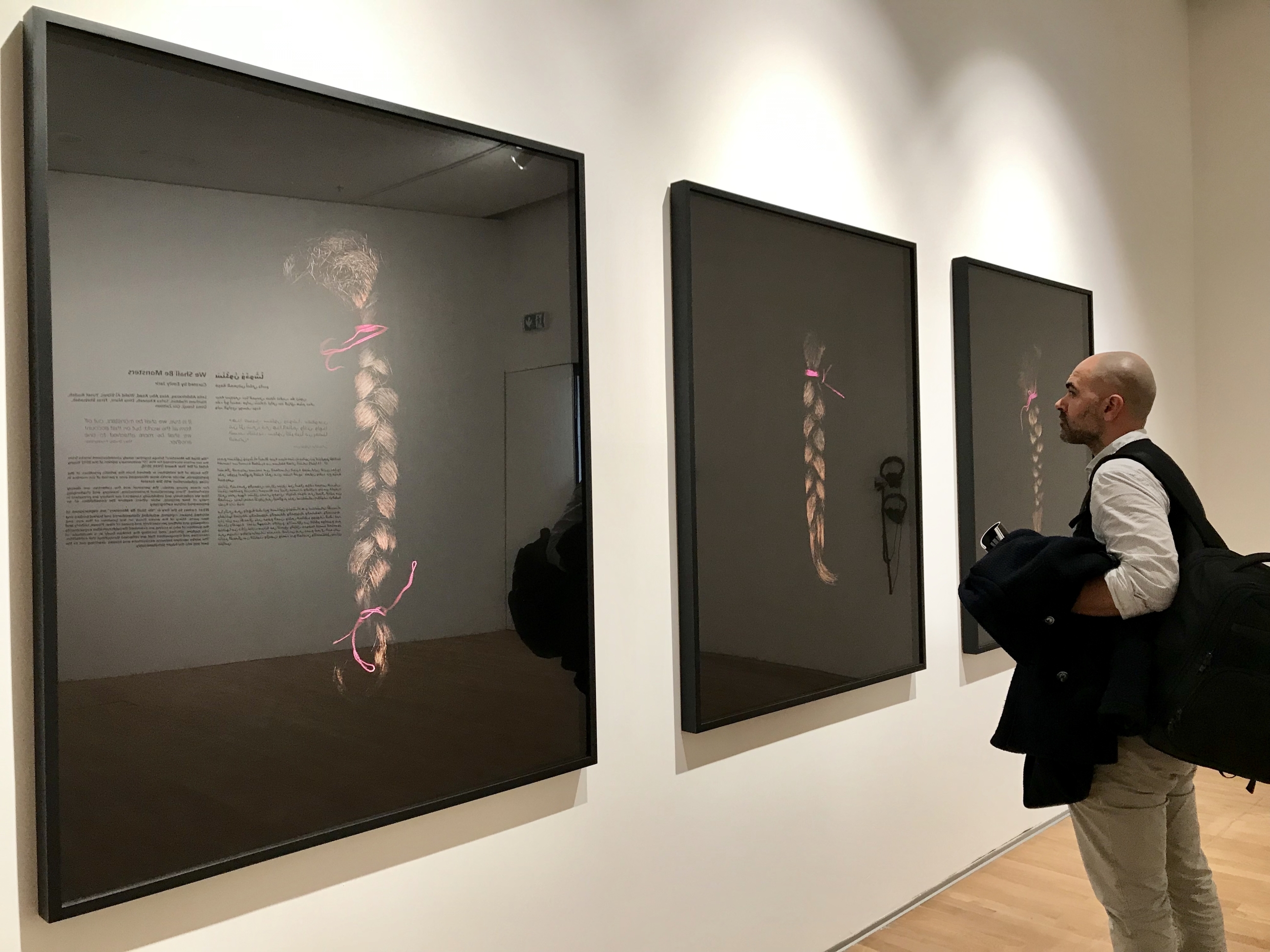

After long consideration, I decided to photograph the braids and develop the images in a dark room I set up in my home in the village of Kafr Kanna, using a scanner at the highest resolution possible. I then showcased three of the braids in large black frames to shock the viewer through its magnification.

I sought to capture the emotional state of the girls behind bars cutting their hair. By using a flatbed scanner, I removed all barriers to the subject including even a camera lens that would have functioned as an intermediary between the young women and the audience.

The braid’s curls provide a metaphorical illustration of the body laying in its cell, between life (light) and death (darkness) above this 'body' attempting to subdue and punish it

The position of the braid’s curls provides a metaphorical illustration of the body laying in its cell, between life depicted by the light emitted from below and death depicted by darkness above this “body”, attempting to subdue and punish it in prison. These attempts fail to break the women physically or emotionally, and only bolster their strength and resilience.

In the depths of solitary confinement and oppression, the incarcerated teenage girls gave something precious to help and encourage other women on the outside fighting to stay alive.

They declared war on two types of cancer: the oppressive occupation and the medical diagnosis those women were battling - confronting both through a simple act of resistance and solidarity.

I eventually donated the braids on behalf of the 13 prisoners to the Dunia Women's Cancer Center in Ramallah, an act on their part that has become more impactful and meaningful over time.

The exhibit, called "The Braids Rebellion", won the 2018 Qattan Foundation Young Artist Award, and captured the theme of “life as origin”. The achievement wasn’t mine, however; it was a gift to those young women from the spirit of the late Palestinian artist Hassan Hourani.

Each year during Breast Cancer Awareness Month, people around the world show solidarity with cancer patients, urging women to seek early detection and testing before it kills their mothers, sisters, relatives, and friends.

Embodying this spirit, in October 2017, Palestinian youth in the Shuafat refugee camp in occupied Jerusalem shaved their heads to make it difficult for occupation forces to identify the perpetrator of a checkpoint attack on an Israeli soldier.

The occupation continues systematically killing men and women alike, in the cities and along the borders, at checkpoints and in bus stations, at the hands of its military officers or its armed settler militias.

For more than seven decades, Palestinians have battled the cancer of occupation which has afflicted every aspect of our lives including our physical bodies. As such, we have resisted our occupiers using a variety of innovative methods - with the body long serving as a first tool of resistance.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.