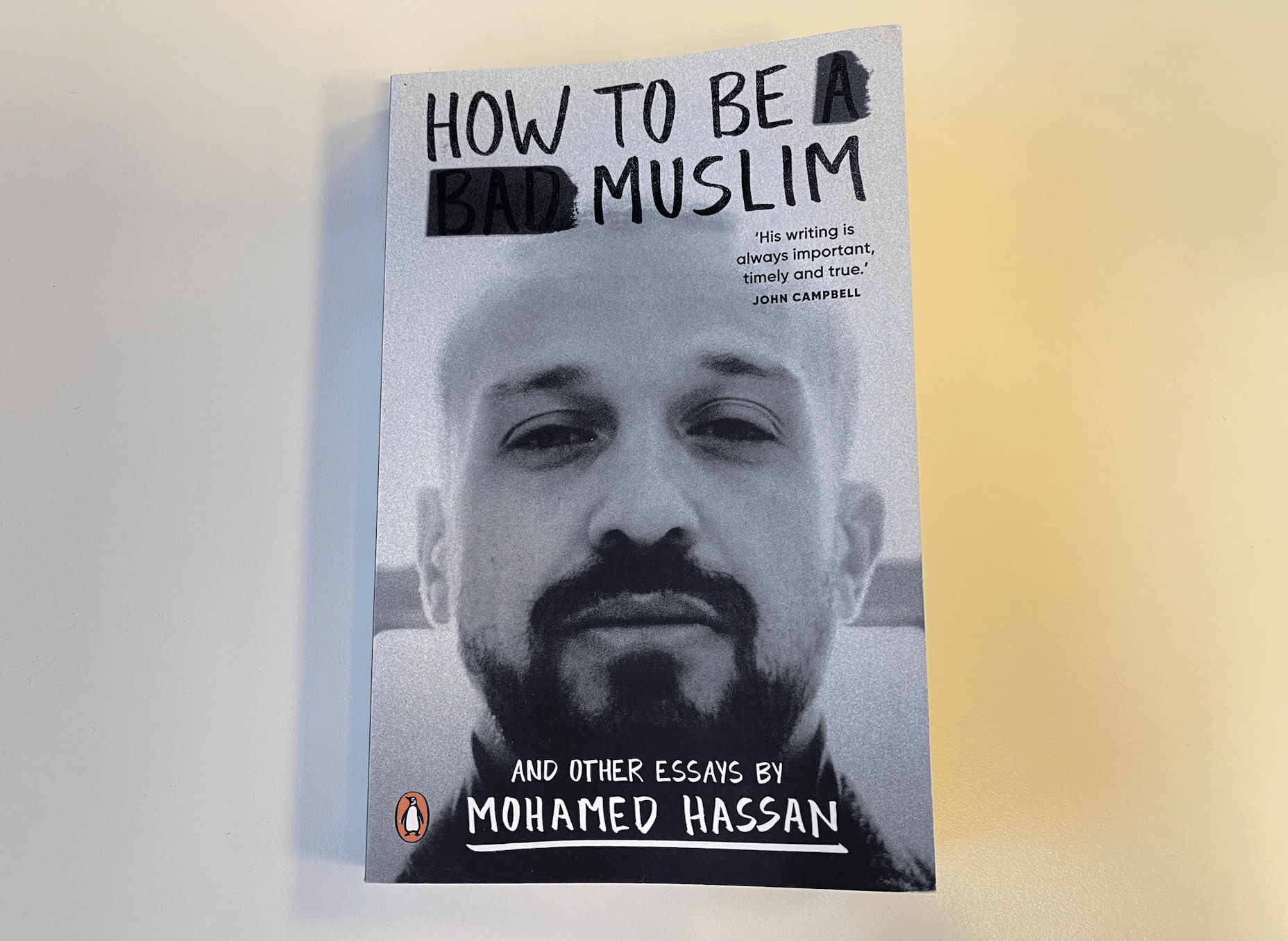

How to be a bad Muslim: Politics, poetry and finding love beyond the labels

Where are you from? No, where are you really from?

It’s a question that’s come to light recently in the British media and it’s a question asked to almost every person of colour. Anyone with a slightly different accent or hairstyle or threads that bear an undefined culture.

It’s a question that’s been asked to Mohamed Hassan, a 31-year-old blue-eyed writer with an unplaceable face and an undetermined accent. And it’s an answer he gives through his poem When They Ask You…

"Tell them about the moon,

how she eats at your skin,New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on

Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

how she gives birth to herself and dies…"

Try saying that next time the question of origin comes up, it should be enough to stop any follow-ups of further explanations.

In the beginning…

For the unacquainted, Hassan is an Egyptian-New Zealander now living in London after a spell in Istanbul. He is both a poet, and the head of video at Middle East Eye's London office.

Born in Cairo, to parents who were both electrical engineers, Hassan grew up surrounded by the love of his grandmother, slow Friday lunches of fried shrimp and molokhia, and afternoon naps - "a sign of true living" - he writes in his new book How to be a Bad Muslim.

At age eight, Hassan migrated with his parents and two younger siblings to Auckland’s North Shore in New Zealand, escaping the economic woes of Egypt in the 1990s.

Having left the banks of the Nile behind, the Hassans' new home across the world was on a street serendipitously named Nile Road, "surrounded by caterpillars, new migrants, and kind, old faces".

A young Hassan would soon be spending weekends kayaking in the lake close to his red-brick corner house.

School days involved standing up to bullies, and following in the footsteps of migrants before him, by seeking out "other kids with weird accents and better food".

It's personal anecdotes like these that form the base of Hassan's book, part memoir part reportage. But, like its author, the book has so much more to offer.

Hassan, wears many hats including that of a journalist and a performance artist, and his award-winning poetry is probably what he is best known for.

Infused with the ethics of faith and family, his poems are never frivolous but instead fuelled with the ferocity of purpose, finding ways to start conversations around issues of importance, to him, to his friends, and to the world.

'Targeted, ostracised and caricatured'

It's this poetic force, blended with the directness of a journalist, that Hassan now drips and drizzles throughout his new book, written as a collection of 19 deeply introspective personal essays.

He tells Middle East Eye: "Even through the process of writing this book, my editor had to keep pulling me back gently from getting too abstract in my writing, and keeping my ideas and imagery grounded and easy to understand. This is my Achilles heel as a poet.

"But as a journalist, there were a lot of tools that felt instinctive, especially when documenting some of the facts around Islamophobia and immigration policy as it exists in New Zealand, Australia, and other places."

Each chapter can be read as stand-alone snapshots of life, or consecutively as a refreshingly honest take on the world’s current state of affairs, through Hassan's eyes.

'Over the last two decades our communities have been targeting, ostracised and caricatured'

- Mohammed Hassan, author

"I had always been fascinated by personal essays," he says, "and really think some of the best writing today is happening in this medium. It's creative and flexible, personal and political all at once."

Hassan took most of 2021 to write the book which deals with everything from counter-terrorism measures to on-screen representation. In one chapter he dips into explaining the history and creation of Arab national flags, and in another how alcohol was once important in pre-Islamic Arabia, and why that changed, reminding the reader, "this is not a commentary on alcohol - it's about the intentions we invest".

Humorously he describes how Arabs don't need alcohol to have a good time: "Remember the Arab Spring? Completely sober... large-scale riots, still sober."

But in his personal sphere, as the only teetotaller at office parties, in societies where alcohol is used to lubricate social interactions, Hassan is witness to racist slurs, unwanted romantic exchanges, and embarrassing dance moves: "I was a silent witness to all of it, and as a result no one trusted me."

His lifestyle choices - framed by religion - are an example of how he becomes "othered", and it's a concept this book challenges to address, as the dangers of "othering" can lead to destructive consequences.

Islamic values feature throughout the book, but never in a preachy way.

Hassan says: "I've endeavoured to write about Islam here in a way that I never have publicly before, not in terms of political identity, but in terms of faith and the ways Islam shapes my day-to-day life and my response to the world around me."

The book was written, he says as: "A personal document of a moment of time that me and my generation of Muslims have lived through. Over the last two decades, our communities have been targeted, ostracised, and caricatured."

Bad Muslim

In explaining the ordinariness of being Muslim, the affable writer explains how "othering" communities can cause harmful narratives and violent actions.

The title of the book was ironic says Hassan: "I'm not calling anyone a bad Muslim, no one is good or bad, but they are labels created for us and we had to fit in. A good fit equals good Muslim, a bad fit equals bad Muslim."

Chapter 11 shares the title of the book, and here we learn of an event that would go on to make Hassan realise his Muslimness was sometimes all that is ever seen.

In 2014, while working for the New Zealand state channel, news broke of a hostage situation at a busy Sydney cafe. The gunman had been identified as a Muslim Australian.

As Hassan helped cover the story, finding people on the ground, he began to notice a distinct hostility from his colleagues in the Auckland news channel. Avoiding his gaze, keeping talk short, he writes, "I couldn't help feeling like my presence was weighing on everyone around me…" He felt like an intruder, realising his colleagues were "terrified" of him.

The act was publicly condemned by Muslim leaders, but this wasn't enough, lines had been drawn.

"Two categories now existed in the public narrative for how Muslims were described: the Good Muslim and the Bad Muslim," writes Hassan.

The first is moderate, doesn't take the Quran too seriously, and "they left the trauma of their countries of birth behind them". The bad Muslim: "Despite their outward law-abiding nature… secretly wished for the demise of Western values."

Post 9/11 world

Hassan was just 11 when the 9/11 attacks happened, killing thousands and forever changing a Muslim’s place in the world when the gaze turned from indifference to suspicion.

His teenage years were formed in the ash clouds of the attacks, long after the debris of that day had been cleared. Mix this with teenage angst and Hassan describes growing up as he: "Struggled to form an identity that didn't betray the demands of immigrant exceptionalism and the mosque."

He tells MEE: "The effects of the War on Terror on ordinary Muslim communities, and the identities of young Muslims, are only just beginning to be understood, and it was my hope [this book will] add to that canon of work that I believe is important in helping us understand how we got here and how to move forward."

He hopes, through the book, other Muslims will connect with an experience that feels similar to their own, and for non-Muslims: "To see the world through our lens and glimpse into the conversations that we have been having between each other for years about what identity and belonging means, how we can exist and survive as Muslims in the West, and what the impacts of key events, like the Christchurch terror attacks, are shaping our responses to the world."

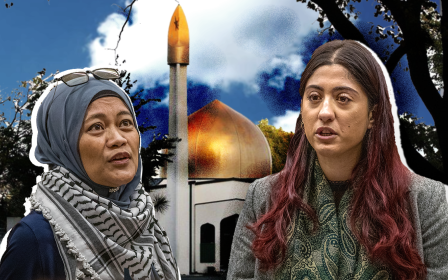

Christchurch

Working as a journalist for the TRT news channel in Istanbul, Hassan heard that a gunman had killed 51 worshippers in two Christchurch mosques.

He was sent back to New Zealand for work to tell the story of loss and heartbreak from a community his family was still part of.

At his UK book launch he explained: "The Muslim community [in New Zealand] had known they were 'othered' for a long time but did they expect an attack of this kind? Of course not. This was the worst violent attack New Zealanders had faced since colonialism."

The nation was forcibly awoken, creating a chance for the world to begin to understand what happens when hate for the "other" silently builds up.

Ashley Kingham, a fellow New Zealander also at the launch, said Hassan had described the society they had both grown up in perfectly. The book, he says, was relatable, not just to Muslims or New Zealanders or to Muslim-New Zealanders, but to everyone.

"Hassan taps into an authentic and realistic multicultural New Zealand that we all recognise but rarely read about, and brings into view perspectives that mainstream often fails to voice."

The Christchurch massacre forms much of the book's backdrop - it's all related you see - and it's this ability Hassan has to bind life’s ordinariness to politics, to religion, to society, where his writing really shines through.

All connected

Skilfully pirouetting between poet and journalist, he has the ability to connect what at first may seem unrelated, to fit perfectly together.

The book opens with a chapter titled Subscribe to Pewdiepie (a Swedish YouTuber named Felix Kjellberg). There’s uncertainty as to why this is important and where this is going, but his conversational style of writing pulls the reader in, wanting to know more about YouTube influencers. With each turn of a page he slowly builds up to a crescendo, when jaws drop and the dots suddenly connect.

In fact, it’s all connected: the power of social media platforms, extremist ideology, and the horrific Christchurch shootings.

He does it again in the ninth chapter Always Watching.

The spiritual is beautifully illuminated here using poetic prayers, with Hassan describing the sacrosanct connections between the heavens and their Creator, with silent night prayers. Pages later he introduces the ever-watchful gaze of the Egyptian secret police and government informants in New Zealand - the jump from elegiac writing to hard facts shouldn't work, but it does.

It's his unpretentious writing style that makes this book so authentic. There’s no feeling of being talked at. But instead, it’s as if he’s sharing his deeply personal feelings with friends - who play a big part in his life and in the book - and we’ve been invited to listen in.

Growing up, Hassan writes he "felt confined by the clashing definitions of Islam, Kiwiness and masculinity."

It's a period he's able to look back on with an understanding of the mental illness that once hovered above him, as he tried to follow paths laid out by family and society.

He dutifully studied engineering at the University of Auckland as a means of pursuing a financially stable career. Feeling suffocated by having to make choices that weren't his, he found himself seeking outlets for the creative expression that simmered inside, this came in the forms of music, poetry, and writing.

On-screen representation

There's joy found in Hassan’s storybook description of his grandmother creating "a handful of paper people" cut from old newspapers on Friday afternoons, sacrificed to the stove-top flames while uttering prayers. Hassan's never been certain of the meaning of this ritual but thinks it stems from an ancient custom to protect from the evil eye.

Years later while watching an episode of the Arab-American TV show Ramy, Hassan sees his grandmother's ritual depicted on screen: a paper chain of people, carefully cut and then set alight.

It may not have been the on-screen representation he had expected, but the scene was a step towards validating identity and experiences, that lit up Hassan's eyes.

In another anecdote, he discovered Rami Malek's lead character in the show Mr Robot spoke Arabic just the way he did: "Like an eight-year-old trying to repair the root of a dying tree."

It's in this Ode to Elliot Alderson where Hassan discusses the limited onscreen representation he saw growing up, a combination of Osama bin Laden in the news and the "hairy tour guide", Omid Djalili's character Gad Hassan, that played up to the racist narrative in the popular 1999 Hollywood film The Mummy.

Representation is important for Hassan, for his nephews - to whom he dedicates the book - and so he takes matters into his own hands.

"I am writing an upcoming comedy series called Miles From Nowhere with my partners Ahmed Osman and the great comedian Aamer Rahman," he says.

The show, being created by his own production company, Homegrown Pictures, will cover everything from counterterrorism to Muslim dating and will be on our screens by late 2023.

Whether his grandmother's traditions will make the cut in his new show remains unclear, but her prayers for him to find the right girl and settle down, lead us to the last chapter.

A place called love

Love in all its forms is subtly woven throughout the book. It’s in the familial love he describes for his parents, siblings, and nephews, it's in the prayers he reads when connecting to God, and it forms a thin line when crossing over into acts of violence and hate.

Hassan ends his book with what's dearest to him, cleverly using the different Arabic stages of love - that can vary from between seven to 24 - Hassan settles on a rounded 10, describing his own personal ascent into the mysteries of the heart.

In a style different from the rest of the book, this chapter is written directly to his now wife. Dancing us through the back and forth of his emotions - starting with "hawa" (attraction) and spiralling into "gharam" (fervour), the couple’s deep attachment culminates in their wedding, with Hassan finding love, perhaps the only place we all really come from.

How to be a Bad Muslim is now available to purchase from Penguin Books Australia

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.