Netflix: Why the idea of Black Cleopatra is so controversial for Egyptians

More than two millennia ago, the Egyptian queen Cleopatra found herself in a power struggle with her younger brother Ptolemy XIII for control of her country.

The two had been co-rulers but the legendary queen was forced into exile by her brother’s powerful ministers.

Sensing an opportunity to exploit the discord in the resource-rich Nile region, Roman leader Julius Caesar set sail for Egypt with the ostensible aim of helping negotiations between the siblings.

Setting up camp in Alexandria, Cleopatra made sure she would have the powerful Roman’s ear first.

According to legend, she had herself wrapped in a carpet that was brought to Caesar's chamber, revealing herself as it was unrolled.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Whatever the truth of the anecdote, Caesar was charmed and the two became one of history’s most famous power couples, with Cleopatra giving birth to Caesar’s son, Caesarion.

For more than two millennia the legendary figure of Cleopatra has fascinated historians and has become a mainstay of popular depictions of Egypt.

Her later relationship with Caesar’s general Mark Antony was immortalised by Shakespeare and is one of literature’s great romantic tragedies.

Despite no consensus on what she looked like, Cleopatra has become a byword for beauty and feminine charm.

But in recent months, her memory is being contested less for her political and romantic escapades and more for what colour she may have been.

A new Netflix documentary drama, Queen Cleopatra, has sparked outrage in Egypt for its depiction of the famed queen as a Black woman.

Leading the condemnation is Egyptian official Mostafa Waziri, secretary general of the Supreme Council of Egyptian Archaeology, who has described the film as a “blatant historical misconception”.

Waziri is backed by Egyptian MPs, including one who has called for the entire streaming platform to be banned in the country for its attack on “family values”.

Egypt backlash

To refute the idea that Cleopatra was black, the Egyptian government has released a statement and images of historical depictions of the queen.

They include a statue bust in the classical Greek style, as well as coins that depict her side profile.

According to the officials, these depictions prove that Cleopatra had "white skin and Hellenistic characteristics".

They also point to the queen’s ancestry, which as a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty is Greek in origin.

The family is named for Ptolemy I, a general in Alexander the Great’s army, who took over Egypt after the breakup of the great conqueror’s empire after his death in the fourth century BCE.

While the Greeks would have intermarried with the local Egyptian population, the sub-Saharan component of such unions is subject to speculation with there being no substantial evidence for Cleopatra having significant black ancestry.

The origin of Black Cleopatra

So where does the idea of Cleopatra being black come from? The Classics scholar and critic of Afrocentric readings of Egyptian history, Mary Lefkowitz, discusses the origin of the claim in her 1996 book, Not Out of Africa.

In it, she attributes the source of the claim to Jamaican-American writer JA Rogers, who includes a profile of Cleopatra in his 1946 work World’s Great Men of Color.

She argues that Rogers wrongly asserts that one of Cleopatra’s unidentified grandmothers was black due to descriptions of her as a slave.

Lefkowitz says this is based on a misunderstanding of the nature of slavery in the Greek and Roman societies and that those civilisations enslaved people regardless of skin colour and ethnic background.

Rogers includes the claim that Cleopatra was seen as black as far back as the 16th century. He cites Shakespearean references to her “tawny” skin tone in Antony and Cleopatra, which he says is synonymous with the archaic term “mulatto” for someone with mixed-race parentage.

There is also a line in the play, in which the Egyptian queen seemingly refers to herself as having black skin.

“Think on me, That am with Phoebus' amorous pinches black And wrinkled deep in time.” Cleopatra says.

While Lefkowitz concedes Rogers is on “firmer” ground with these arguments, she ultimately dismisses the assertion he makes as a misreading of figurative language as literal. That said, whether the quote is a description of Cleopatra’s skin colour is still subject to debate within Bardolatry.

A vociferous critic of Afrocentrism, Lefkowitz does not view the claim by Rogers in isolation but as part of a wider Afro-American movement that began identifying with Ancient Egyptian achievements in the early 20th centuries.

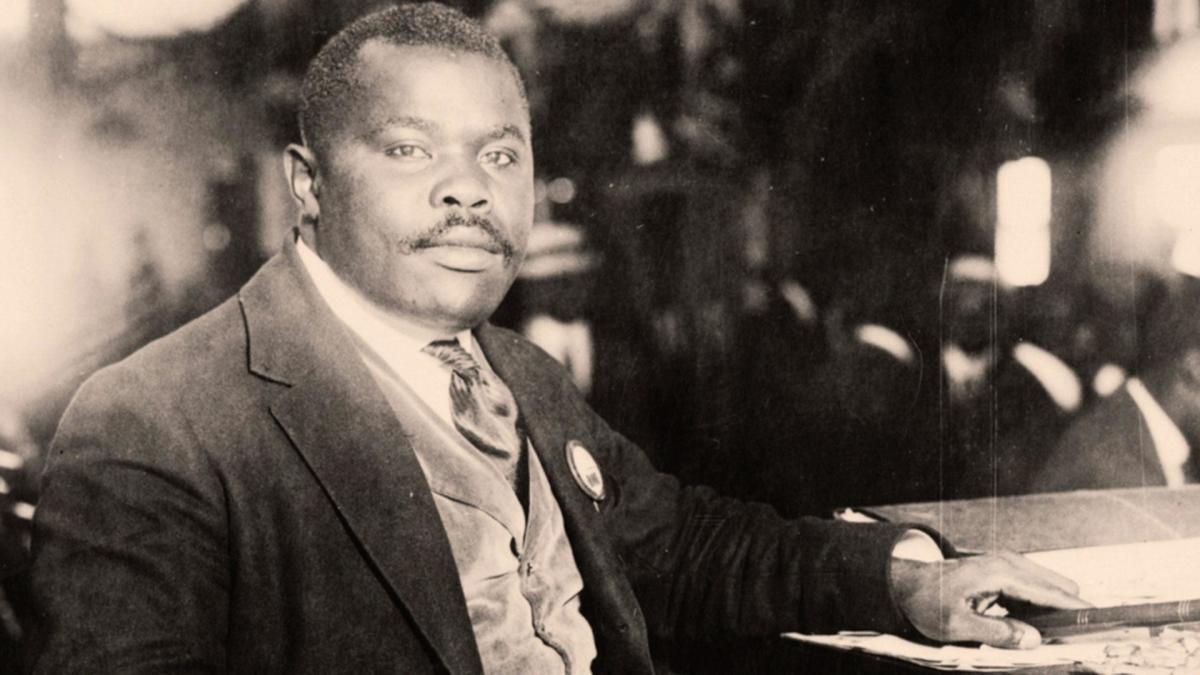

In an introduction to a 1996 collection of essays called Black Athena Revisited, Lefkowitz, who co-edited the book, specifically singles out the Black nationalist and pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey for helping to popularise the idea.

Garvey had made the claim that Ancient Egypt was a Black African culture and that the scientific and philosophical achievements of its people had been appropriated by European civilisations, such as the Ancient Greeks.

Explaining his reasoning for such thinking, Lefkowitz writes: “Garvey thought of history as a means of instilling self-confidence in a people who had lost faith in themselves and had been compelled to lose touch with their past.”

An influence on the Nation of Islam and figures like Malcolm X, Garvey died in 1940 but remains one of the most important Black nationalist figures of the early 20th century.

The title Black Athena Revisited was a response to Cornell scholar Martin Bernal’s book Black Athena, which argued that Hellenic civilisation was deeply influenced by African and Semitic cultures and that those contributions were later downplayed by scholars of the Classical world.

While considered a landmark work in Classical studies, Bernal’s research is rejected by most in the field. For his part, Bernal criticised Lefkowitz for what he saw as her narrow-minded approach in dealing with the issue of Egyptian and other Near Eastern contributions to Greek culture.

In any case, Bernal’s definition of “African” was not synonymous with Black people and included North Africans of lighter skin tones.

Afrocentrism and Egypt

Opposition to perceived inaccurate representations of Ancient Egyptian figures is strong in Egypt and the more recent episode involving Netflix is the latest in a string of controversies there.

Earlier in 2023, the American comedian Kevin Hart’s Cairo show was cancelled for his purported Afrocentric views.

Hart reportedly said Black Africans were “kings in Egypt” but the veracity of the quote has never been established. Regardless, Egyptians have accused the Get Hard star of “Blackwashing”.

Egypt’s problem with “false” representations of its culture and history is, of course, not limited to the casting of Black African actors.

'We’re not crazy about Elizabeth Taylor playing Cleopatra either'

- Bassem Yousef, comedian

That sentiment was summarised in a recent debate hosted by British commentator Piers Morgan and featuring Egyptian comedian Bassem Youssef.

The latter clarified that Egyptian objections extended also to white actresses who had played Cleopatra, including the famous 1963 film starring Elizabeth Taylor.

“We’re not crazy about Elizabeth Taylor playing Cleopatra either. It was also inaccurate. I don’t know where you get the idea that we are happy that she played the role,” he said of the performance, adding that Taylor was banned from Egypt in the aftermath of the release for her pro-Israel stance.

For decades, Egyptian citizens and politicians alike have complained about how foreign media has portrayed their country.

The upcoming biopic, Cleopatra, has also been slammed for the decision to cast controversial Israeli actress Gal Gadot in the eponymous role. In that instance the film was criticised for “whitewashing”.

Such controversies are not limited to the character of Cleopatra. Ridley Scott’s 2014 epic Exodus: Gods and Kings starred Christian Bale as Moses and featured a main cast that was almost entirely white.

The movie was banned in Egypt for its alleged “Zionist” bias and “historical inaccuracies” and was ridiculed online for its Eurocentric casting.

According to the scholar Ahmed Diaa Dardir, the co-founder of the Institute for De-Colonising Theory, while anti-blackness may represent a small aspect of the response to the Netflix documentary, the main driving force for the Egyptian response is the idea of people who are not from Egypt excluding Egyptians from tellings of their own stories.

“Egyptian responses to representations of Cleopatra are multifold. While there were rare yet unfortunate expressions of anti-blackness, I believe the general frustration is with Netflix’s attempt to impose certain narratives as politically correct,” he told Middle East Eye.

“My understanding is that the Egyptian backlash is less about Afrocentrism - after all Egyptians are African - and more about a western trend that depicts modern Egyptians as outsiders to their own country and heritage,” he continued.

“It is indeed part and parcel of how Hollywood is ready to imagine that anyone (including aliens), but not the Egyptians, built the Egyptian civilisation.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.