The Book of Delights: A medieval text that helped give rise to Indo-Pakistani cuisine

In the soft light of September, Ala-Too Square in Bishkek appears magical with its graceful central fountain surrounded by rose bushes.

The air carries the captivating aroma of roses and freshly baked pastries and as the late afternoon unfolds, the square begins to buzz with activity.

Many of the visitors to the area hold tiny paper plates or paper bags containing a snack called Samsa.

This is a mixture of minced lamb and rich layers of fat enveloped into a triangle-shaped pastry.

The name and description might seem familiar to a seasoned gastronomer.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Variably known as Sanbusak, Sanbusa, Samusak, Samosa, and Singarea depending on which part of the world between Morocco and Bangladesh one is, the dish encountered in the Kyrgyz capital is the ancestor of the famous South Asian pastry.

Over the centuries, the snack has come to symbolise the eclectic mix of cultures that have left their imprint on the subcontinent’s cuisine; evidence of India's inextricable ties to Central Asia.

Around 3,400 miles away in London's British Library, lies a text that contains one of the earliest extant recipes of the samosa.

Known as Kitab Ni'matnama-i Nashirshahi (Nasir Shah's Book of Delights), or Nimatnama for short, the 15th-century book was a medieval equivalent of a recipe book, packed with lavish miniature illustrations of dishes being prepared and handwritten annotations.

Visitors to the library's Treasure's Gallery will find a copy close to Shakespeare's First Folio and illustrations by Michaelangelo, unfolded on a page detailing a recipe for a samosa, made of minced meat, onions, dried ginger, garlic, and aubergine.

Historic mentions

The Samosa made its first appearance as a side dish called 'Samusak' in the early 1300s. Amir Khusrau, a Sufi singer, scholar, and poet from the Indian subcontinent, mentioned it while describing an aristocratic Muslim meal. He said it was a wheat casing filled with meat, onions, and deep-fried in ghee.

Nearly fifty years later, Ibn Battuta, an explorer and scholar from the Maghreb region, assumed the role of Qazi at the court of Muhammad Bin Tughlaq, the Sultan of Delhi.

While he eventually became a victim of court intrigues that would force his departure from India, in his six years in the region, the Moroccan traveller diligently documented everything he observed, including the culinary practices of the elite classes.

In his travelogues, he writes: “They served meat cooked in ghee, onion, green ginger in China dishes…Then a thing called samosa (samusak) is brought; minced meat cooked with almonds, walnut, pistachios, onion, and spices placed in a thin bread and fried in ghee. In front of every person are placed four to five such samosas.”

In his book, A Historical Dictionary of India Food, food historian K.T Achaya talks about the two centuries preceding Mughal rule in the late 15th century as a period when there was a surge of innovation and creativity in cooking.

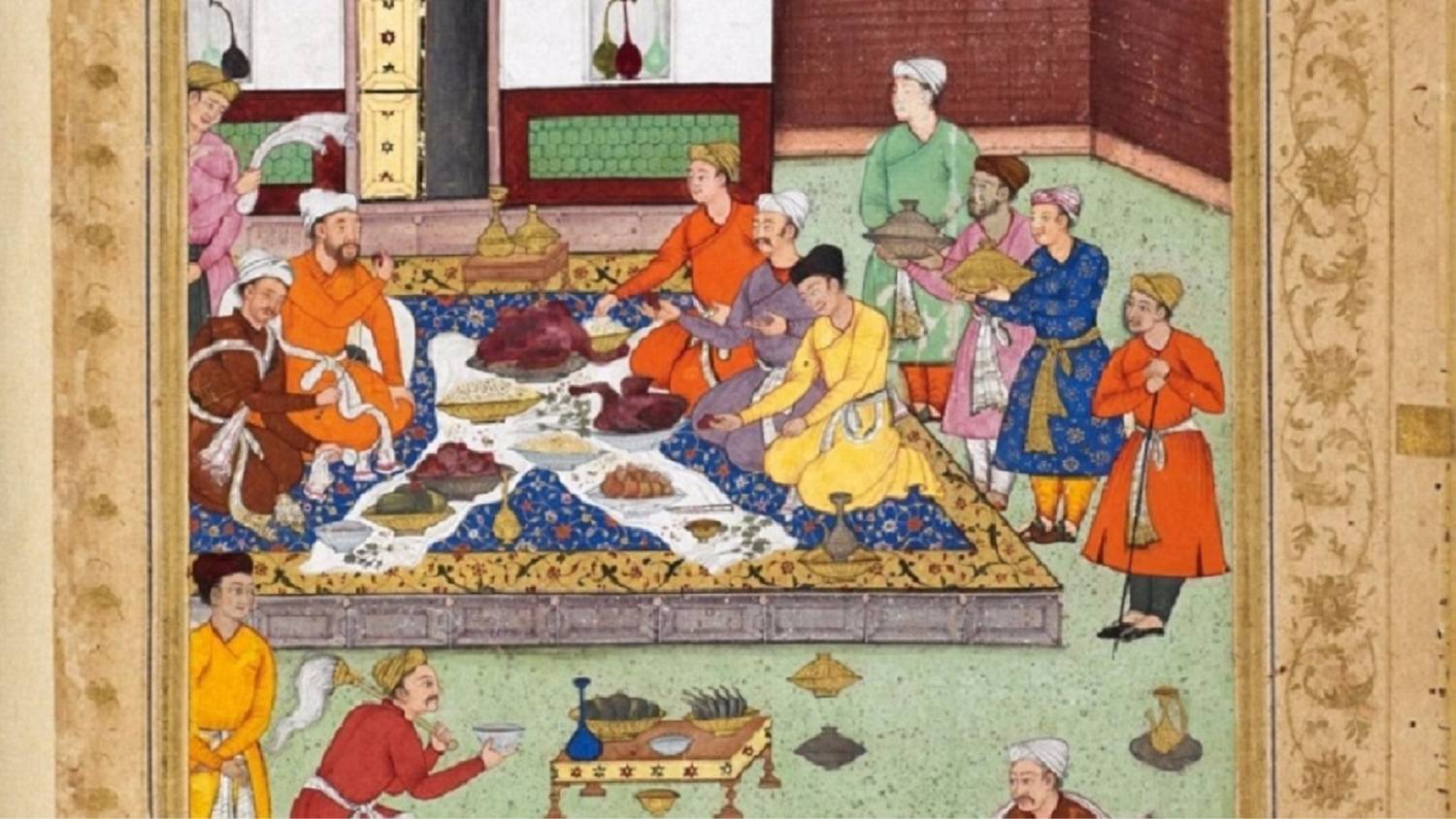

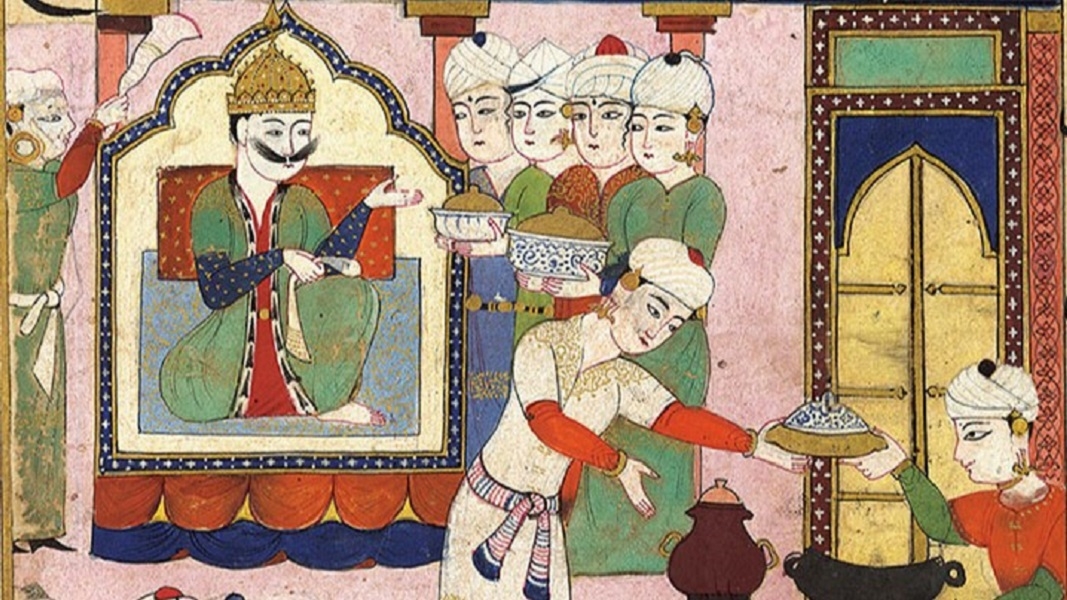

In the courts of various princes, food became a means of indulgence and there was a great emphasis placed on concocting new culinary delights.

It was during this period that a number of South Asian staples began to take their modern forms, such as biryani, nihari, and pilau, alongside many other dishes.

New recipes were codified in lavishly illustrated books, which often included detailed recipes for the dishes described.

The Book of Delights

The Nimatnama was one such book and stands as a notable achievement within India’s culinary literature.

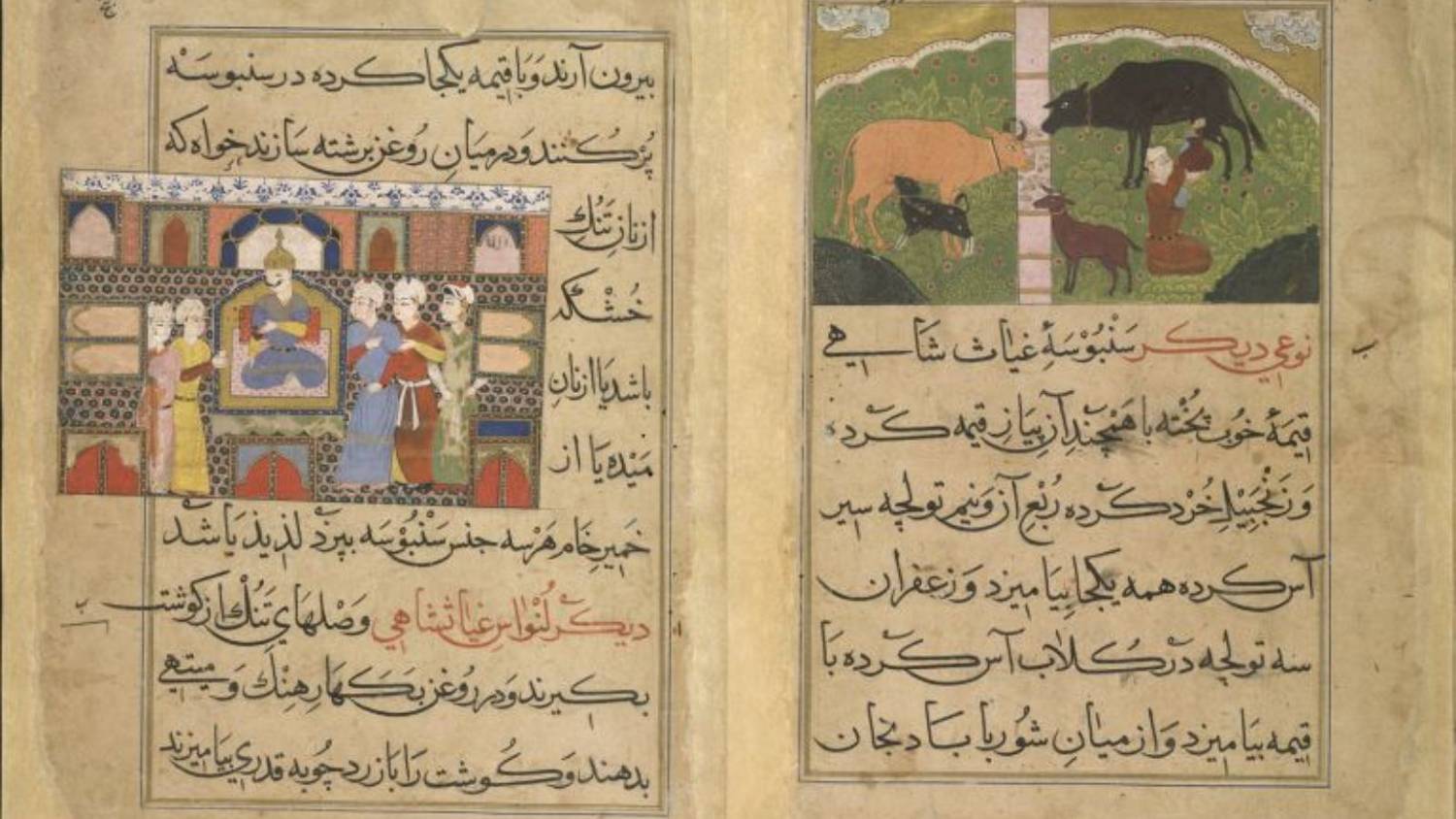

A Persian language project undertaken by the Sultan of Malwa Ghiyath al Din Shah Khilji, known as Ghiyath Shah, between 1469 to 1500, the work was later expanded and completed by his son Nasir Shah, who gave the text his name. The completed culinary manual would eventually boast fifty surviving illustrated folios.

Beyond being a mere collection of recipes, the book offers a treasure trove of Epicurean delights and valuable insights into the history of consumption, eating experiences, new ingredients, and the personal food preferences of the unnamed writer or patron. Remarkably, it even speculates about future trends in gastronomy.

Norah Titley, the translator of the original manuscript housed in the Oriental and India Office Collections of the British Library, offers valuable insights into the contents of the book.

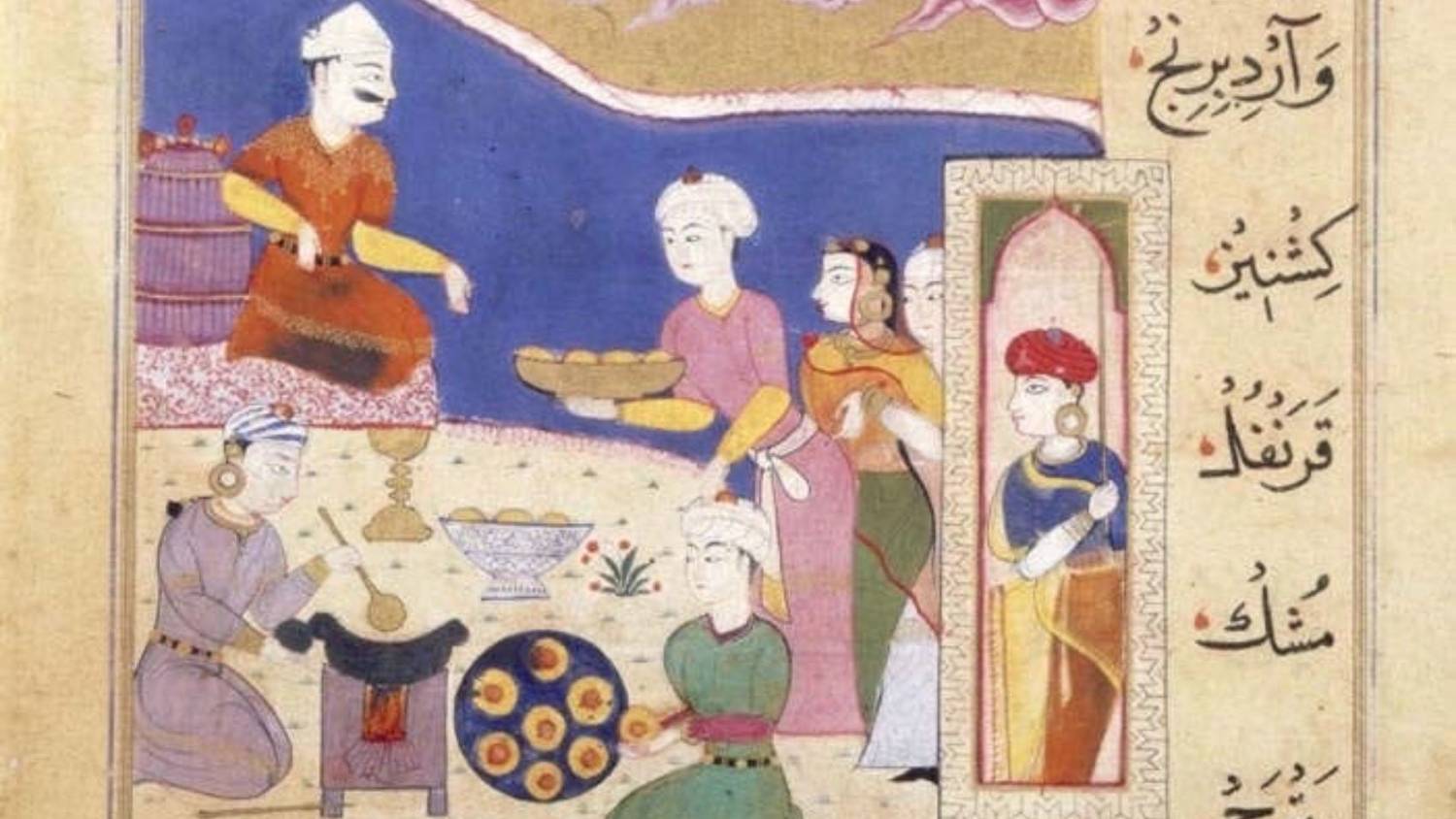

She describes how some miniatures have minute words written alongside them, possibly as a guide to the artist, indicating specific activities to be illustrated, like the word "sanbusa" alongside the miniature illustrating the preparation of samosas.

While recognising the historic importance of the text, Titley also highlights some challenges that may render the book difficult to use as a recipe book today. She says the text can be cryptic and abbreviated, assuming knowledge that may be lost to modern readers. Quantities are rarely provided, and sometimes, even the provided quantities can be incorrect. However, despite these difficulties, the text offers unique insights into medieval Indian life, making it a valuable historical document.

Aside from the diverse recipes, The Book of Delights also captivates readers with its illustrations, showcasing a distinct Indo-Persianate style.

While the miniatures initially bear the influence of the Persian 'Turkman' art from Shiraz, they progressively adopt a more Indianised form, reflecting Ghiyath Shahi's liberated approach to life, one that refused to be confined to a single form.

The shah’s reign commenced in 1469 and was characterised by a focus on indulging in pleasurable pursuits, with the hope of inspiring his subjects to share in the same interest.

In a departure from day-to-day rule, Ghiyath Shah passed on the governance to his son Nasir Shah, allowing himself to pursue artistic and intellectual interests, such as music, arts, crafts, and bookmaking.

During this period, the capital of Malwa, Mandu, earned the epithet "City of Joy," reflecting the vibrant and joyful atmosphere that prevailed at the time. And it is this libertine air that is captured within the text of the Book of Delights.

In the volume, Critical Muslim, Food in Islam, the late Welsh Muslim scholar Merryl Wyn Davies delves into our relationship with food and its connection to the era we live in.

Emphasising that eating is an essential human need, she argues that the way we approach food profoundly impacts the course of human development, often leading us into the complexities of the modern age.

This argument can be extended to historical cookbooks like the Nimatnama, offering a glimpse into the culinary culture of the medieval, and early modern period in South Asia, loosely referred to as the Mughal period (1526-1857).

The significance of the Nimatnama also lies in its role as a precursor to other culinary texts written during the later Mughal regime, including Ain-i-Akbari (The Administration of Akbar), Alwan-e-Nemat (Colours of the Riches), and Nuskha-i-Shahjahani (Shah Jahan's Recipes).

Together, these texts, along with the Nimatnama, contributed to the rich culinary heritage of the region, leaving a lasting impact on South Asian cuisine.

Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai says that the influence of such books on identities and food choices in South Asia contributed to the formation of what we now recognise as Indian "national cuisine".

A vivid example of this culinary transformation can be seen in the case of the samosa.

Originally a snack with Persian and Central Asian origins, the samosa has evolved to become a quintessential food item that beautifully reflects the way of life in South Asia.

Deeply intertwined with the region's culture, the samosa is often associated with the tradition of "adda", which refers to the engaging conversations that occur in both public spaces and homes. This connection to the leisurely lifestyle of South Asia has led the samosa to be considered a "national identity" for both India and Pakistan.

The Nimatnama and the birth of Mughlai cuisine

The opening pages of the Nimatnama describe a variety of samosas and their fillings, ranging from condensed milk and minced meat to cooked pulses.

One description of how to make a type of samosas reads: "Take five sirs [measures] of good grains of pure wheat, put one sir of sweet-smelling ghee into it and grind it by hand and pound it with a wooden pestle.

"When it is well-mixed, prepare slices of mahicha [meat], paste the thickness of a finger and fry them in ghee. Put the fried paste amongst roses so that it acquires a sweet smell, then knead it by hand and crush it so that it becomes fragmented.

"Add pot herbs, musk, camphor, cardamom, and cloves and mix them all together. Stuff the samosas, fill them fully and pick them up by hand."

In another description of how to make shorba (soup), a recipe ends with the remark that the dish is “delicious”.

The connection to contemporary Indian cuisine is evident in the familiar names of ingredients and cooking methods still popular today, like bhagar (spice tempering), bara or bari or wada (fermented and deep-fried ground pulses), karhi (chickpeas in spices and sour milk), papar (deep-fried dal wafers), laddu (sweetmeat), and rabari (pottage in buttermilk or curds).

Surprisingly, all these names are also a familiar part of Indian vegetarian cuisine, defying the notion that the Sultan's project was solely meat-based.

The Nimatnama also introduces generic terms and methods integral to modern Mughlai (North Indian and Pakistani) food, including yakhni (broth), seekh (skewered), karhai (wok), kebabs, biryan (baked rice), sherbet, and kufta (meatballs).

A long list of spices and condiments includes cardamoms, rosewater, cloves, dried ginger, pistachios, raisins, walnut, almonds, pine kernels, onions, coriander, fenugreek, cumin, beetal leaf, asafoetida, edible camphor, musk, and zafaran (saffron), all of which are still used.

In terms of cooking techniques, the manual emphasises flavouring and marination, which are also characteristic of present-day Mughlai culinary practices.

Current regional cuisines have adapted these inherited legacies to local materials and tastes, sometimes incorporating external influences.

As Mughal rule progressed, gastronomy became more ornate and sophisticated. The affairs of the kitchen were an important part of court life, with dedicated rakabdars (gourmet chefs) for specific dishes.

For instance, someone would exclusively prepare pulao or a particular meat dish throughout their employment.

The Book of Delights undeniably had a significant impact on Mughal cooking, as evident in similar descriptions of Yakhni or Haleem in later writings.

It is believed that the book reached the imperial library after Akbar defeated the last ruler of Malwa, Baz Bahadur, in 1562.

Amidst controversies and debates over Mughlai food's origins, the story of the early modern cookbook Nimatnama cannot be overlooked.

This five-hundred-year-old book was pioneering and set the trend for the hybrid, cosmopolitan styles that would go on to shape the Indian subcontinent's food culture for centuries to come.

Because of this, its influence is still felt in both the modern food choices and the culinary heritage of countries across South Asia.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.