From Mecca to Jizan: Exploring the forgotten heritage of Saudi Arabia's Hijaz province

In January 2023, I travelled to Hijaz to perform the minor Islamic pilgrimage, or Umrah, and then made my way south to visit the southern provinces of Saudi Arabia.

The plan was to follow the Sarawat Mountain range that runs parallel to the eastern coast of the Red Sea and take it all the way down to Jazan, the last province bordering Yemen.

The region of Hijaz is located in the western third of the country and is home to the two most sacred Islamic cities, Mecca and Medina.

However its rich history and significance predates Islam. For thousands of years travellers and caravans passed through it to reach Yemen in the south, or the region of Greater Syria in the north.

Historically, Hijaz was the most important region in all of the Arabian Peninsula with Mecca as its commercial and spiritual hub.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

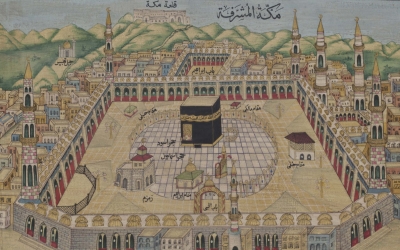

With the arrival of Islam, the importance of Hijaz was renewed. According to Islamic tradition, the Prophet Ibraham (Abraham in Biblical tradition) founded the city of Mecca with his son Ismail, and together they constructed the Kaaba, God’s first House of Worship.

The Prophet Muhammad, a native of Mecca, revived the old monotheistic traditions of Abraham in the sixth century and united the tribes of Arabia under one faith.

The historic Hijaz

Most of the formative battles and episodes of early Islam took place in the Hijaz, such as in Tabuk and Taif, cementing the role of the entire region in Islamic history and tradition.

The northern region of Tabuk, for example, was the location of a major military expedition late during the Prophet Muhammad’s career, in which he sought to unite Arab tribes under Muslim leadership against the Byzantines further to the north.

Taif was a city the prophet visited early in his spiritual career to spread his message and in the hope of winning supporters to protect him from his increasingly hostile clansmen in Mecca

As Islam expanded, the old caravan routes once used for trading with Mecca and Medina were used to transport pilgrims.

The three main routes to Hijaz originated from Damascus in the north, Basra in the northeast and Sanaa and Aden in the south.

As the capitals of the Islamic world shifted outside of Hijaz to Damascus, Baghdad, Cairo and later Istanbul, the northern and eastern routes increased in significance while the route to Yemen fell into decline.

The importance of the northern route is documented by the fact that many Muslim rulers, from Saladin in the 12th century to Suleiman the Magnificent in the 16th century, heavily invested in infrastructure and security for pilgrims.

Then in 1908 the Ottomans began constructing the Hijaz Railway, a train line which when finished, would connect the imperial capital of Istanbul to Mecca, serving pilgrims and providing an economic and military network between distant Ottoman territories.

Though the project was never completed, a route was established between Damascus and Medina. There were no plans however of establishing stronger links with southern Hijaz or Yemen.

This historical neglect of the southern Hijaz has shaped the way the geography of Hijaz and Saudi Arabia as a whole is viewed today.

Outsiders assume the whole Arabian Peninsula region to be dry, hot and mostly flat, following the desert topography of what’s known as the Rub al-Khali (Empty Quarter).

However the south of Hijaz, which historically included north Yemen, is incredibly different and diverse in its climate and geography.

The south is made up of four provinces: Al-Baha, Asir, Jizan and Najran.

While the average rainfall in most parts of Saudi Arabia is below 150mm per year, these provinces get between 400mm and 600mm annually and are on average 10 degrees Celsius cooler, making them perfect escapes from the desert heat.

They also include the highest peaks in the country, some of which are home to lush green valleys.

The Hijaz today

After completing the umrah, I departed from Mecca and headed towards Taif, a city famous in Islamic history as it had been visited by the Prophet Muhammad.

The city is a popular summer destination for locals and has unofficially been called the "summer capital" of Saudi Arabia for its many mountain resorts, a status it has maintained since ancient times.

The road to Taif takes travellers onto the Sarawat mountain range which features ancient routes used for thousands of years.

It reaches a flat plateau at some points, and then spirals down and crosses valleys at others.

Taif is located on top of one of these plateaus reaching 1,800 metres above sea level, reached by driving up a zig-zag road around a cliff edge, which cuts through clouds and provides incredible views along the way.

Known for its plentiful date palms, sweet grapes, figs and honey, Taif is a major agricultural contributor in Hijaz. Something that would not be possible without its high altitude and fertile soil.

The city’s elevation has also acted as a natural defence barrier for centuries, providing it with excellent fortification. Like all of Hijaz, Taif was once under Ottoman rule from the 16th century onwards but not much evidence of this era remains.

Beyond its agriculture and resorts, Taif is also where Ibn Abbas, a cousin and companion of the Prophet Muhammad, is buried.

It is a custom amongst pilgrims who visit Mecca to make the short journey to Taif to visit the few religious sites located here.

After Taif, I headed further south towards the province of Al-Baha, once called the "Garden of Hijaz", famous for its pleasant climate and numerous forests, 53 in total, that surround it.

There are interesting opinions on the etymology of Al-Baha, but some interpret it to mean "abundant water" or "open space", and it is easy to imagine why.

Like Taif, the city of Al-Baha sits atop the Sarawat range, making it much cooler and greener than the dry and hot plains of Mecca, 300 kilometres away.

A short drive away from Al-Baha is the village of Thee Ain, named after a nearby spring that flows through it.

This eighth-century CE village was built on the summit of a mountain, which according to Unesco is “famous for its cultivation of bananas, lemons, pepper, basil and traditional handcrafts”.

The houses are built out of polished stone with multiple floors, stacked side by side and on top of each other; a wonderful example of ancient urban village organisation and design.

Unfortunately no longer inhabited, the village today serves more as a museum.

The Saudi Tourism Authority, which hopes to draw greater tourism into the area, has financed its refurbishment.

There is however a small community that inhabits the area around the mountain, and who maintain and farm the land.

Lush palm trees and other fruits are still grown and two mosques serve the ancient village to this day.

While I stood on the summit of Thee Ain, the call to prayer could be heard throughout the mountain range.

Asir province

I continued the journey south, travelling another 333 km to cross into the Asir province, home to the tallest peaks in the country, with some reaching 3,000 metres at Jabal (Mount) Sawda.

Asir, along with Jizan, borders Yemen and was once famous for producing coffee, wheat and frankincense.

Legend has it that Aelius Gallus, a Roman ruler from Egypt, crossed into this region in 25BCE under the order of the Roman Emperor Augustus to take control of a trade route between the Mediterranean Sea and Yemen. The expedition was a failure, and for almost a millennium, the region of Asir remained unexplored by outsiders.

From the top of these peaks, I entered the Al Soudah National Park from where an observer can see small inhabited communities nested between the feet of these enormous mountains.

There are mountains densely covered with juniper trees as far as the eye can see, rising up to meet the thick layer of clouds.

It is also hard to not notice the presence of another natural phenomenon: baboons. The Sarawat mountains are the native home of hamadryas baboons, a species of primate that can be found all across this region.

In recent years, these baboons have travelled further north, and have been spotted across urban areas around Mecca.

Travelling down the mountain range I arrived at a small village known locally as Rijal Almaa.

Once, caravans crossing from and to the Levant, Mecca, Medina and Yemen stopped here, making this a regional trade centre.

Like Thee Ain, this village has many stone houses stacked on top of each other, but here some houses reach up to seven stories high.

These ancient skyscrapers reflect the architectural language found in Yemeni cities like Sanaa.

This village too has been abandoned for many decades, and is now marked as a future tourist destination, though there were no other visitors during our visit.

Surrounded on most sides by mountains, there are strong signs that nature is reclaiming this ancient settlement.

After a further three-hour drive south, we reached the southernmost province of Jazan, where desert flatlands, scattered palm tree oases, mangroves, and tall grasslands host flocks of camels and other animals.

The image of ancient Bedouin Arabia was shattered soon enough. Jizan is also home to one of Saudi Aramco’s largest oil refineries. Tall flare stacks burning flammable gas, seen miles away, provide a strange backdrop of a modern and industrial Saudi Arabia amid the beautiful virgin sandy coast of the Red Sea.

I stopped at Baish Corniche, a 1.7km long public park, funded and constructed by Saudi Aramco. The site includes numerous children's parks, gyms, a football field, and many restaurants and cafes.

Billions are being invested in turning Jizan into a regional economic hub, and it shows.

Driving into the city centre, one sees no trace of an ancient village or settlement, but instead row after row of tall cranes and construction sites.

If southern Hijaz has been neglected in literary and historical imaginations, and deprived of economic activity for centuries, its fate might be changing.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.