Obituary: Oman's Sultan Qaboos Bin Said, a moderniser with an iron fist

Oman's Sultan Qaboos bin Said died on Friday evening at the age of 79 after a long illness, marking an end to almost 50 years of rule.

The sultan took the throne of an extremely underdeveloped country with a history of civil conflict and oversaw its transformation into a politically stable middle-income state during his half-century reign. Under a model of modernising absolute monarchy, he largely managed to steer Oman away from the extremes of consumerism of neighbouring Dubai and the religious conservatism of Saudi Arabia.

The concentration of political power and wealth in the sultan's hands, combined with the absence of a clear route to succession, had led to fears that there could be a leadership crisis following his death.

The two most commonly mentioned successors were Qaboos' cousin, Sayyid Asaad bin Tariq al Said, and the latter's son, Taimur.

However, the appointment of Haitham bin Tariq, Oman's culture minister and the 65-year-old cousin of the late sultan, on Saturday appeared to put to rest lingering uncertainty over the country's succession process.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Under Qaboos, political parties were banned and laws of lese-majesty created an all-pervasive system of surveillance and repression that ensured no organised opposition could emerge. Those who spoke out would face arrest or come under intense pressure from the state and even family members to stay loyal and avoid public criticism.

Still, there is no doubting the genuine affection in which the sultan was held by many Omanis and expatriates, seen as a visionary leader who had secured the welfare of Omanis and expatriates alike by leading the nation through its modernisation, and leaving a legacy that his successor will be hard put to equal.

The last years of Qaboos's life were plagued by illness and led to long absences from the country for medical treatment in Europe. He was often out of the public eye, while still receiving diplomatic visitors including UK and US politicians.

He had recently returned from Belgium where he was receiving medical treatment, reportedly for colon cancer.

Qaboos was a stalwart ally of Washington and London, ever since he was installed by a British-backed coup against his father in 1970. Oman was discomforted by the Gulf crisis of 2017, in which Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates imposed an economic blockade on Qatar, a close ally of Oman.

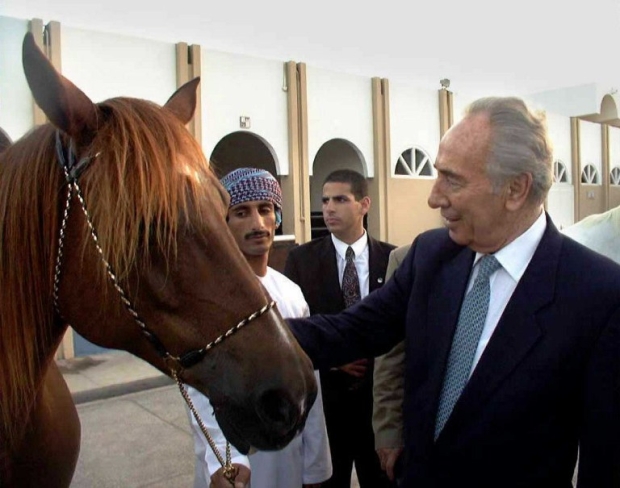

In late 2018, Oman, which has cordial relations with neighbouring Iran, appeared to pivot toward the Middle East strategy of US President Donald Trump's administration with a surprise visit to Muscat by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who met Qaboos at his palace.

A royal coup

Sultan Qaboos was born in Salalah, in the southern Omani governorate of Dhofar, on 18 November 1940, the only son of Sultan Sayyid bin Taimur and Sheikha Mazoon al-Mashani. He was educated in Salalah and briefly in India. Oman was then under the British imperial umbrella, and, as the young heir to the long-reigning al-Busaidi dynasty, Qaboos was sent to a British private school in Kent and then the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst for military training.

The sultan's father suspected Qaboos of wanting to overthrow him. On returning from Europe he was held under virtual house arrest at the royal palace in Salalah. However, bin Taimur allowed two British officers go to Salalah and remain with Qaboos in his palace confinement.

At the time the officers in Sultan bin Taimur's army, the SAF, were all British. One of them was Tim Landon, who had been a close friend of Qaboos at Sandhurst. Landon planned the coup with allies in Petroleum Development Oman, then a British-run company, and with the mayor of Salalah. Together they plotted to get Sultan bin Taimur out of Oman and to London.

Bin Taimur resisted but only managed to shoot himself in the foot. He died two years later in exile, where he was living in London's Dorchester Hotel. Official Foreign Office papers on this period are still restricted.

The legend of the country's national day was born on 23 July 1970, when Qaboos succeeded to the throne. In his deep-voiced English diction, he told a waiting BBC journalist why he had overthrown his father: "Because I thought my father was not leading the country in the right way he should have been leading it," adding, "I had some friends and they helped me."

The young sultan, aged 29, had to contend with a communist-led rebellion in the Dhofar region that was backed by the neighbouring Yemen Democratic Republic. The country was isolated and wholly dependent on its relations with Britain, with no diplomatic ties with Arab neighbours or international bodies.

Rapid development

Qaboos began quickly to reverse this by joining the League of Arab States and the United Nations. Saudi Arabia was one of only two countries to vote against Oman joining the UN.

Domestically, Qaboos embarked on a policy of rapid economic and social development, starting from a position in which the country had only 10km of tarmac road, two primary schools and no secondary schools, and two small hospitals run by American missionaries.

The oil sector provided a growing export income which, with the increase in global oil prices in 1973, became the foundation of an oil-rent state.

In 1974, Oman followed the nationalist trend in developing countries at the time by taking a majority stake in Petroleum Development Oman, which until then was 85 percent owned by Royal Dutch Shell with France's Total holding a 10 percent stake. The shareholdings have remained unchanged to this day, with Oman's minister of gas and oil acting as chairman of the company.

With revenues from oil, the first export of which began just a few years before he succeeded to the throne, Sultan Qaboos was able to forge a new social contract with a politically fragile and divided population. According to Marc Valeri, director of the Centre for Gulf Studies at the University of Exeter, the bargain was one of "political quiescence in return for public services, subsidies, public-sector jobs and little or no taxation".

The sultan inherited a conservative, highly religious country riven by armed insurrection and tribal divisions, Valeri wrote, and over several decades, reduced the influence of the tribes, while incorporating their leaders in the political process.

Qaboos handsomely rewarded the small number of British officers who facilitated his rise to power by helping to overthrow his father, none more so than his close confidant Landon, who in the decades following the succession of Qaboos built up a lucrative business empire in the country.

Landon was also responsible for bringing in many officers into the SAF from white-ruled Rhodesia, where he had strong links and owned land, and from apartheid South Africa, regardless of the racist views many of them held.

Oman was one of the countries involved in a clandestine plot, alongside Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, to subvert international sanctions against the South African regime by diverting oil tankers with papers for other destinations to South Africa. Apartheid leaders Pik Botha and FW de Klerk both visited Muscat to thank Qaboos for the oil that had allowed them to survive the sanctions imposed on them by the international community.

Cultural steps and quelled protests

Qaboos married his cousin Sayyidah Nawwal bint Tariq al-Said in 1976, but the marriage did not produce any children and ended in divorce in 1979. He never married again. A veil has discreetly been drawn over the sultan's personal life since then and it remains a taboo subject in the country's media.

The nation that emerged under his leadership is a relatively open, multicultural society, which has relied heavily on foreign labour from Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa in its process of construction and development. In the last decade or more a policy of "Omanisation" has had some limited success, putting more Omanis in senior positions within companies that were previously occupied by westerners.

Qaboos also championed the advance of women, gradually opening the way for many to enter education and the labour market in increasing numbers, despite Oman being a conservative society that traditionally segregated women in domestic roles.

In 2013, Oman was lauded by social scientists as the most advanced in terms of the participation and rights of women in the Arab world, falling only behind the Comoros Islands.

Qaboos was also a big supporter of the arts with his government sponsoring the country's first societies of artists and traditional music. As a lover of classical music, he played the organ and the lute, composed music and founded the Gulf's first symphony orchestra in 1985, its players recruited from the towns and villages of Oman.

In 2001 he ordered the construction of an opera house in Muscat, the first in the Arabian Gulf. It opened in 2011 with Placido Domingo leading a performance of Turandott. Its repertoire of western and international music caused opposition among religious conservatives, leading to occasional protests.

In 2011 unrest swept the region, and Oman was not immune. Protests broke out in the industrial port city of Sohar in the north, and spread to other parts of the country. Security forces were deployed and many protesters were arrested and jailed.

Qaboos responded to demands for greater social opportunities and an end to high-level corruption in the country by firing some long-serving ministers, while also initiating a massive expansion of jobs in the public sector, raising the minimum wage for nationals and liquidating of private mortgage debts that many Omanis had acquired during the boom years.

As elsewhere in the Gulf, a mixture of repression and increased state spending successfully quelled discontent. However, human rights campaigners and independent bloggers have continued to fall foul of lese-majesty censorship laws, which forbid criticism of the sultan and his government, leading to the arrest of dozens of activists and journalists since 2011.

Under Qaboos, Oman had among the highest per capita military spending in the world with a 2016 budget of $6.75bn out of total state budget of $30.9bn. More than just a defence force, the armed forces act as the social and political glue of the Omani state, with thousands of young people embarking on a career in the military each year, in which they obtain a secure livelihood and privileges alongside what is available the other main national institution, the state oil company PDO.

Navigating regional and international diplomacy

The sultan was a stalwart ally of the UK and the US during the Cold War and in regional disputes. Qaboos saw the country's security best served by a close alliance with western powers, which he believed would protect Oman from the nationalism sweeping the Arab world and also from the regional ambitions of Saudi Arabia.

Oman was one of only three Arab states not to break diplomatic ties with Egypt when it signed the 1978 Camp David peace treaty with Israel. In the early 1990s, Qaboos showed his support for US Middle East policy by inviting Israel's prime minister Yitzhak Rabin to Oman - the first public visit by an Israeli leader to an Arab state. He appeared to be returning to this playbook with the visit by Netanyahu in late 2018.

Oman's strategic position in the Gulf became critical for western powers in the years after the 1979 Iranian revolution. In its aftermath, Qaboos signed a 10-year facilities access agreement with the United States, the first of its kind between the US and an Arab country.

Oman's Masirah Island, which had been a base for Britain's Royal Air Force since the 1930s, became the staging post for US president Jimmy Carter's disastrous hostage rescue attempt following the seizure of the US embassy in Tehran. The agreement was renewed in 1990, and Oman sent troops in the US-led war against Iraq following Saddam Hussein's attack on Kuwait.

After the attacks on America in September 2001, Oman was a major Nato logistics base during operations in Afghanistan and Pakistan, with cargo airlifted to Afghanistan on a daily basis via Muscat.

However, Qaboos was careful to maintain diplomatic ties even with those states, such as Iran and Iraq, which were in conflict with his western allies. As he explained to an Egyptian newspaper in 1985: "There is ultimately no alternative to peaceful coexistence between Arabs and Persians, nor to a minimum of agreement in the region."

Qaboos created a paternalistic system of absolute monarchy, the cohesion and stability of which hinged heavily on the authority and popular affection toward the sultan himself. As Marc Valeri wrote: "This model of legitimacy, based on the extreme personalisation of the political system, is intimately linked to the person of Qaboos and to him only."

One of the world's longest-serving heads of state, Qaboos began tentative moves toward a constitutional monarchy in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with the introduction of an elected consultative assembly and municipal council elections. However at the time of his death he remained head of state and prime minister, and commander in chief of the armed forces.

Despite allowing Oman to be used as a military base for "the Great Satan," Qaboos maintained a delicate balancing act in his relations with the Iran, and in recent years developed strong diplomatic and economic ties with Tehran.

Following the Syrian unrest and violence that broke out in 2011, Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies lined up with the rebels and armed and funded their war against Iran's ally President Bashar al-Assad. In contrast, Oman has maintained a strict neutrality towards the sides in the conflict

Qaboos's discreet diplomacy gave the country a reputation of being the Switzerland of the Middle East, holding a midway position in the arch-rivalry between the Gulf Sunni monarchies and Iran. The results of this unique political role came to fruition with the revelation that the Qaboos had hosted bilateral talks between the US and Iran from 2012 that produced the interim deal over Iran's nuclear programme and the first signs of a rapprochement between Iran and the US since the 1979 revolution.

The sultan was the first world leader to visit the newly elected President Hassan Rouhani in Iran in August 2013. In the same year, Oman signed a billion-dollar gas pipeline deal with Iran. In early 2017, Rouhani made his first visit to the Arab world to Muscat, where he was greeted by a frail Sultan Qaboos.

Oman's increasingly independent position in the Gulf created tension with Saudi Arabia. Oman stood out against Saudi Arabia's stalled effort to transform the Gulf Cooperation Council into a political-economic union along the lines of the EU in 2013, going as far as to say that the sultanate would leave the GCC rather than go along with this change.

In January 2015, Muscat lashed out at Saudi Arabia for pushing a policy of oil price reductions through Opec, which left Oman with a serious budget shortfall.

The same independent stance was seen in the Yemen crisis of early 2015, when Oman stood aside from most of the GCC and did not take part in the Saudi-led bombing campaign against the rebel Houthis, later hosting talks between the warring parties in Yemen.

However, the shift in regional politics brought about by the election of Donald Trump, and his close alliance with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, left Oman in an awkward position, given its close friendship with Qatar.

While oil revenues have cushioned the economy of Oman, persistent problems with high-level corruption have remained.

Before his long absence due to illness in 2014, Qaboos appeared to have given the nod to a mini-purge of some of the major perpetrators. In February 2014, the CEO of state-owned Oman Oil Company, Ahmad al-Wahaibi, heir of an elite family with close ties to the sultan, was sentenced to 23 years in prison after being convicted of accepting bribes, money laundering and abuse of office.

In May 2014, Mohammed bin Nasser al-Khusaibi, a former commerce minister, was found guilty of bribing an official $1m to award a contract linked to the new Muscat airport to a company in which he was a shareholder. The crisis around the flagship airport - the opening of which had to be postponed from the end of 2014 to the end of 2018 due to various rumoured problems - typified the issue of illicit profit making among Oman's ministerial elite. Two other senior officials were also jailed in the case.

Qaboos's successor will face the growing question of how to quell rising expectations of a new generation of internet-savvy young people no longer satisfied with the repressive paternalism that prevailed under half a century of Qaboos.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.