Is it a fake? The mystery of the last Ottoman caliph’s secret plan

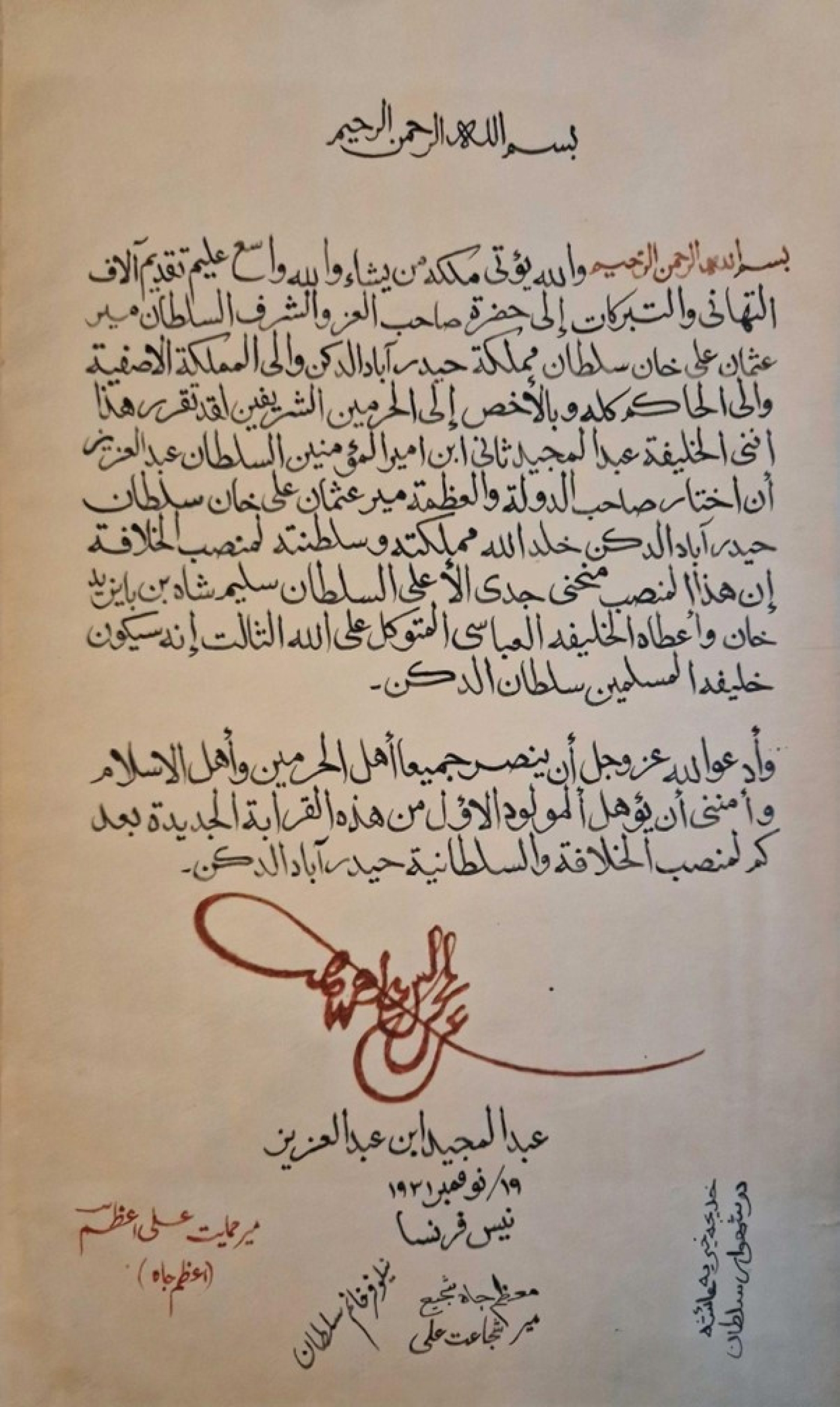

It’s a small piece of paper, nearly 100 years old, inked in red and black Arabic script on thick wheat paper. To the side and at the bottom it is adorned with the names of some of the notables of the former Ottoman caliphate.

The largest signature belongs to the last caliph himself: Abdulmecid II.

Now that document has international experts arguing over a historical puzzle: did the deposed ruler seek to revive the caliphate in India after it was abolished in 1924 by Turkey?

Several academics say the document is a forgery, including prominent Turkish historian Murat Bardakci.

In August, I wrote about the life and plans of Abdulmecid after he was driven out of office. A few days later, on 20 August, Bardakci wrote in the Turkish website Haberturk: “Let me just say this: this document was manufactured a few years ago, so it is a fake!”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

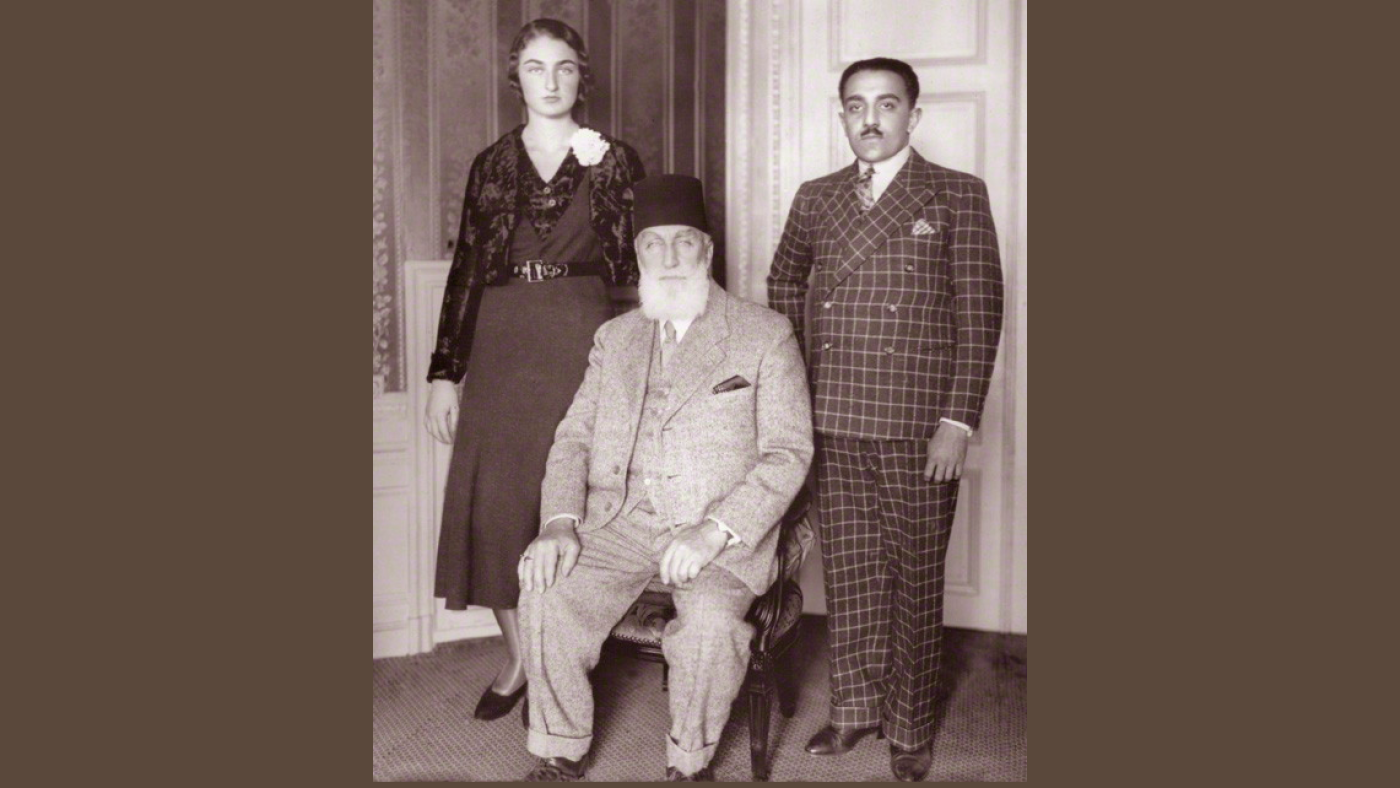

The mystery begins in 1931, in Nice on the French Riviera, when the last caliph of Islam was in exile. In November of that year, his daughter, Princess Durrusehvar, married Prince Azam Jah, the heir apparent of the seventh nizam of Hyderabad.

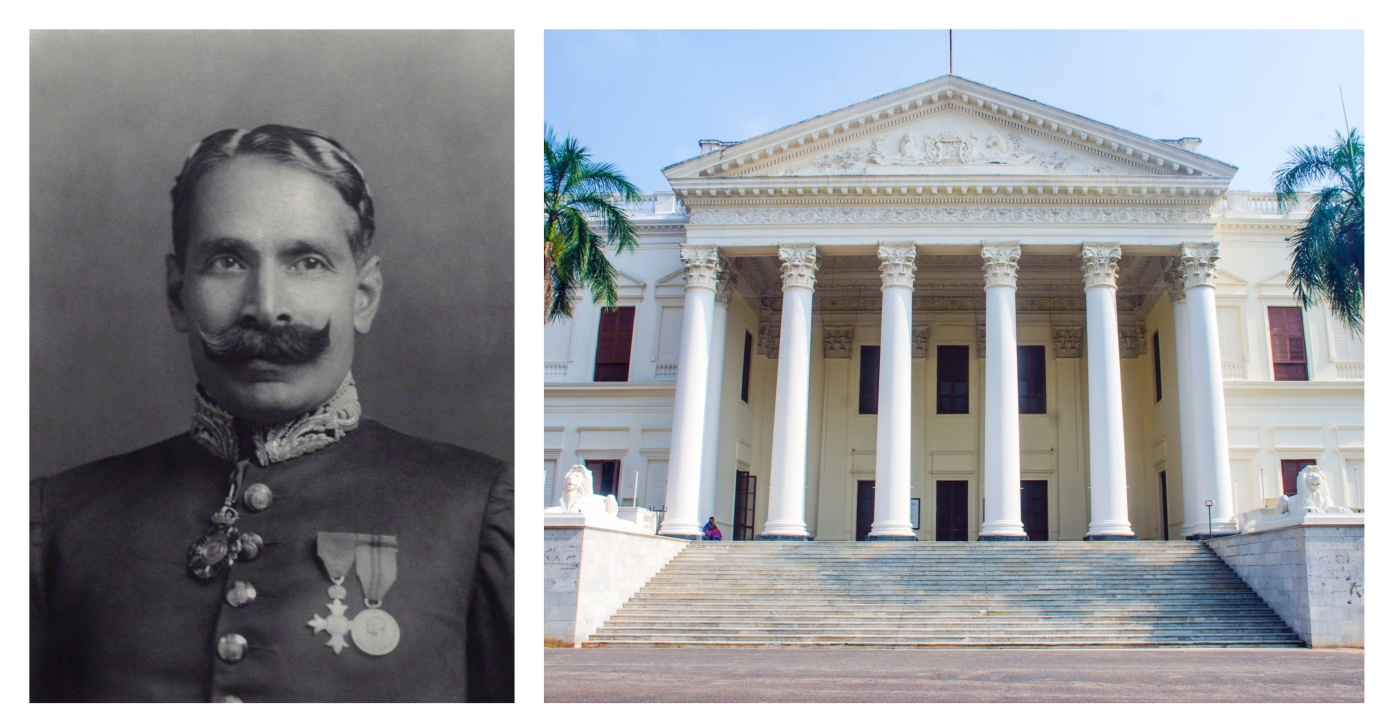

Azam Jah’s father Osman Ali Khan was the Muslim ruler of British-run India’s largest princely state. He was also the world’s richest Muslim - and keen to secure his credentials across Islam through a dynastic betrothal.

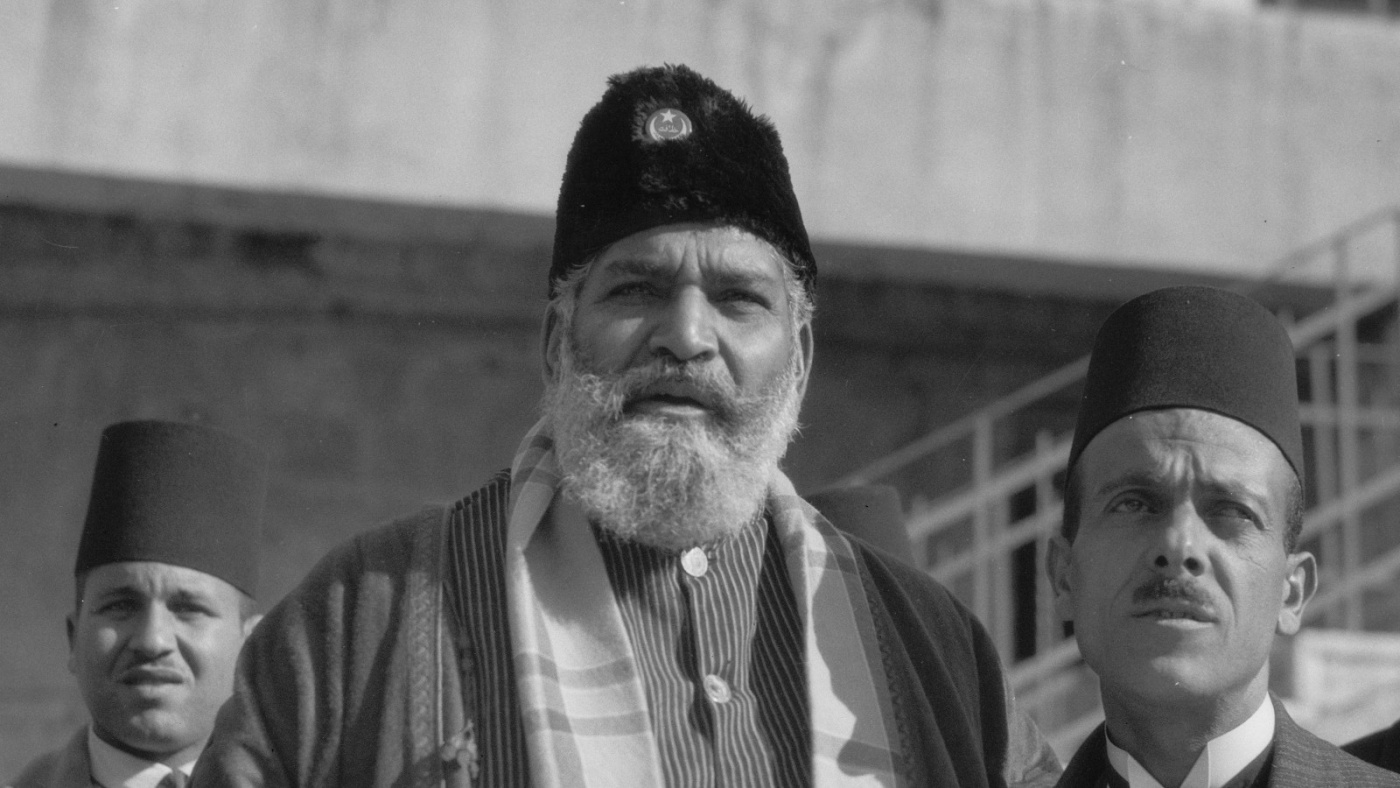

The marriage was brokered by Maulana Shaukat Ali, legend of India’s early independence campaign and former leader of its Caliphate Movement, which had lobbied on behalf of the Ottomans after the First World War.

Internationally, many were aware of the wedding’s political implications, from the Turkish government in Istanbul to the Urdu press in Bombay, from English visitors in Hyderabad to American journalists in Nice.

Before the marriage, TIME magazine reported: “Should these young people wed and have a man child, temporal and spiritual strains would richly blend in him. He could be proclaimed 'the True Caliph'."

But none of the media reports at the time mentioned the secret deed, addressed to the nizam and purportedly signed by Abdulmecid in Nice on 19 November 1931 - a week after his daughter’s wedding.

Through it, Abdulmecid transfers the title of caliph to the nizam. It is to be held in trust before being claimed by the first-born son from the marriage of Princess Durrusehvar and Prince Azam Jah.

The deed concludes: “I trust that the firstborn son of this new kinship after you [the nizam] be suitable to the position of the caliphate and the rulership of Hyderabad Deccan."

Turkey and the ‘Photoshop’ deed

The caliphate is a controversial issue in Turkey: it was abolished in 1924 by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, founder of the nation, after the country became a republic.

The then-Turkish government said it transferred the caliphate’s authority from the Ottoman dynasty to the Grand National Assembly in Ankara. But numerous statements by Abdulmecid show he disputed this, challenging the official historical narrative.

Bardakci is the author of several well-known Turkish books on the Ottomans and regularly appears on TV panels for historical discussions.

Abdulmecid II: Read the caliphal deed

+ Show - HideThe following is a translation of the caliphal deed of Abdulmecid II. It has been translated into English by James Wrathall. An image of the deed follows below.

"In the name of God the Compassionate the Merciful, and God gives His kingdom to whom He wills and God is All-Encompassing, Knowing. We offer thousands of congratulations and well-wishes to His Highness, Possessor of Splendour and Nobility, Sultan Mir Osman Ali Khan, Sultan of the Kingdom of Hyderabad Deccan, Governor of the Asafi Kingdom, Governor and Ruler of it all, especially as far as the Two Noble Sanctuaries. It has been established that I, Caliph Abdulmecid II, son of Commander of the Believers Sultan Abdulaziz, elect the Possessor of the State and Greatness, Mir Osman Ali Khan, Sultan of Hyderabad Deccan, may God eternalise his Kingdom and Sultanate, to the position of the Caliphate. Indeed this position fell to my most elevated grandfather Sultan Selim Shah son of Bayazid Khan, and the Abbasid Caliph al-Mutawakkil 'ala Allah III gave him it. Indeed the Sultan of the Deccan shall be Commander of the Faithful.

"And I beseech God, splendid and glorious is He, that He grant victory to all the People of the Two Sanctuaries and the People of Islam and I trust that the firstborn son of this new kinship after you be suitable to the position of the Caliphate and the Sultanhood of Hyderabad in the Deccan."

In his piece in August, he wrote that while he had not seen the physical deed, “there was no need for me to give detailed information about the physical features of the document.”

The signatures at the bottom, he said, which many observers believe belong to Abdulmecid's daughter, son-in-law, niece and his niece's husband, “had no connection with the real signatures of these people”.

Bardakci also said that friends with contacts in Hyderabad had told him that the document “was produced by a sensationalist journalist via Photoshop, and even found out the name of the journalist!” Bardacki did not name the journalist.

MEE contacted Bardakci about his views. He had yet to comment at time of publication.

Ayub Khan is a Toronto-based researcher and doctoral candidate at McMaster University, who has published multiple academic articles on aspects of Indian history. He told MEE that the authenticity of the deed is doubtful for several reasons.

“It is missing essential stylistic elements of an official Ottoman document including the tughra, included specifically to prevent tampering,” he said, referring to the seal used by sultans.

He also highlighted that official documents were commonly written in diwani, an Arabic cursive script, which was not used here. “Caliph Abdulmecid II was a skilled calligrapher and shouldn’t have had any trouble in drafting the official deed in diwani, even while in exile.”

Khan also said that Abdulmecid’s handwriting in private correspondence did not match that in the document, suggesting it was written by someone else.

And the inclusion of the poetic pen names of princes Azam and Moazzam Jah raises further doubts, Khan said, given these were not conventionally used in documents in Hyderabad or elsewhere.

“All these issues render the document doubtful to say the least.”

India and the ‘ink for princes’

The document was discovered by Syed Ahmed Khan, a nawab (or hereditary Indian lord), in his family home in Hyderabad city in 2023.

The head of the household is his father, Nawab Akram Abbas Syed, who paid for my visit to India after I began writing about the last caliphate in 2023.

The Imam ul-Mulk family has strong historical ties with other parts of the Islamic world: Syed Vicaruddin, its late head, was awarded the Star of Jerusalem, one of Palestine's highest honours for a foreign national, in 2015.

It still publishes The Rahnuma Daily, which was formerly patronised by the nizam, covered the weddings in Nice in 1931 and is India’s oldest circulated Urdu daily newspaper.

Syed Ahmed Khan told me how in December 2021 he was sorting through the papers of his grandfather. Syed Mohammed Amiruddin Khan, the seventh nizam’s military secretary, had died in 2012 aged 99.

The papers included a collection of unpublished handwritten Urdu poems by the seventh nizam; a volume of handwritten poetry by his son Azam Jah; and letters in Urdu from Islamic scholars in Deoband in India and in Arabic from Mecca and Medina, commending the nizam as a Muslim leader.

And then there was the deed.

But Khan cannot read Arabic. In 2023, he showed his grandfather’s papers to Syed Abdul Mohaimin Quadri, who works from his Institute for Management & Conservation of Manuscripts, within the shrine complex of revered saint Hazrat Pathar Wali Sahib, in Hyderabad’s Old City.

Khan said: “I was looking for help to better understand them, and it was during that visit that I learned of their historical importance.”

Quadri told MEE that he rejected accusations that the deed was fake.

“If anyone is calling anything fake, then subject the documents and historical items found in the whole world’s museums to the most rigorous tests,” he said. “They would also all be cast into doubt."

Quadri said that the signature of Caliph Abdulmecid was the same as on other documents. “You can see it exactly to the letter.” The name, he said, was written using red ink from the night-blooming jasmine, which was very old. “This ink was only used for titles or signatures or on very special occasions.”

Meanwhile, the ink used for the rest of the document, Quadri said, was a strong carbon black ink. “If we soaked the document in water for 15 days, the ink would not run. If it was left in water for a month, then a little change would occur. This ink was only prepared for princes or rulers.”

Quadri said of the other signatures: “Azam Jah’s name’s penmanship corresponds with every name found in the manuscripts written by those same hands.”

As to the paper, he noted that it was very strong and made from wheat. “Such paper was used around rulers and princes. It was beyond the means and reach of common people.”

What of the handwriting? “The script is naskh, which would usually be selected for orders and edicts” in India. This suggested that the deed was drawn up by the Hyderabadi delegation, not the Ottomans. The naskh script was often used in Ottoman calligraphy, and in India for official purposes.

And the content of the deed itself? “From the manner of expression, which is in the text,” Quadri replied, “it is clear that these are the words of rulers.”

Quadri is confident that the deed is authentic. Other experts in India concur.

Ahmed Ali, now retired, was a curator of the Indian government-owned Salar Jung Museum, in Hyderabad. He has organised 120 exhibitions in India and abroad, written 80 published articles on art, history and conservation and delivered more than 45 research papers.

He agreed with Quadri on the type of paper, ink and use of Arabic naskh, all of which, he said, pointed to the deed’s authenticity.

“The document ends with prayers for the Nizamate of Hyderabad and the title of the caliphate transfers to the firstborn male of the union.”

Ali also said that the “names along with the Caliph's signature are authentic and match those found on other documents” he had read.

He agreed with Quadri on Azam Jah’s signature, which Ali said matched his handwritten book of poetry, found among Amiruddin’s papers.

Who would be caliph? Infant grandson or son-in-law?

But despite this defence of the authenticity of the deed, questions still remain. One is how did it end up - with the other documents - in Colonel Amiruddin’s possession?

Whatever the truth, there is no evidence or suggestion that the finders of the deed forged it.

Syed Ahmed Khan said that his family accepted the views of Hyderabad’s experts, and that they were custodians of the deed for apolitical, historical and strictly cultural purposes. “We have no ambitions to see the caliphate revived in any political or religious manner.”

But who was behind the document? The caliphate was never ultimately transferred to Hyderabad. The nizam never claimed the title “caliph”. Abdulmecid never stopped using it.

Was the deed drawn up as a secret contingency in case the caliph died without leaving a will?

Alternatively, if the deed was forged, who did it and why? If it was to ultimately claim the caliphate then it failed: the caliphate remained unclaimed.

What is clear is that Abdulmecid wanted Hyderabad to be the future seat of the caliphate. Days after his daughter wed, Urdu newspapers in Bombay reported that the marriage was a prelude to the restoration of the caliphate.

These stories were based on briefings from the politician who brokered the marriage, Shaukat Ali.

Angered at the media attention, the nizam accused Ali of a “breach of confidence”, according to private correspondence between British officials found in the British Library archives. The British government, which governed India from London, told the nizam to cancel his plans for the the caliph to visit Hyderabad.

But crucially, the nizam never accused Ali of fabricating the idea that the marriage had implications for the caliphate - only of being indiscreet.

Was the prime minister telling the truth?

In Nice on 6 October 1933, Princess Durrusehvar gave birth to Prince Mukarram Jah, the grandson of both the caliph and the nizam.

While his grandson was still a baby, the nizam privately told his inner circle that Prince Azam Jah, his own son and Hyderabad’s heir apparent, would now not become the next ruler. Instead the 26-year-old aristocrat would be cut out of the line of succession in favour of his infant son.

In August 1944, Abdulmecid died in wartime Paris.

In a confidential letter to the colonial government in New Delhi in November that year, Sir Arthur Lothian, the British representative in Hyderabad (known as the “resident”), reported to his superiors that the state’s prime minister, the nawab of Chhatari, told him he had seen the late caliph’s will.

Abdulmecid’s final wishes, Chhatari said, were that he be buried in India and that his grandson be the next caliph.

But during my discussions with Ayub Khan, something crucial came to light.

In 1974, Ayub Khan pointed out, the nawab of Chhatari published his memoirs under the title Yaad-e-Ayyam (Memories of Bygone Days).

In the book, Chhatari wrote that the nizam told him in November 1944 that Abdulmecid had named Azam Jah, his son-in-law and husband of Princess Durrusehvar, as the next caliph.

While this establishes that Abdulmecid wanted the caliphal line to pass through the Asaf Jahi dynasty in Hyderabad, it contradicts Lothian’s letter and introduces a new mystery.

Which generation of the Asaf Jahi dynasty did Abdulmecid want the caliphal line to pass through: father or son? Why would the last caliph choose his son-in-law, who was not a direct descendant, as his successor? After all, Abdulmecid must have known that the nizam had quietly designated Mukarram Jah as his heir.

Chhatari never mentions in his memoirs, which cover events until 1948, that Mukarram Jah had been selected as the nizam’s heir when he was still young - a significant omission. And while it would not have been public knowledge at the time, it was crucial as to who Abdulmecid would have designated his successor.

One reason for the contradiction between the accounts may have been their intended audiences. Lothian’s letter was private correspondence, ultimately for the British viceroy of India, on a matter of government intelligence. In contrast, Chhatari’s book was published for public consumption.

The whereabouts of Abdulmecid’s will are still unknown. The precise truth is, for now, beyond reach. But on the balance of probabilities, it seems that Mukarram Jah, rather than his father, was the designated successor to the caliphate.

Death of a caliph and final intentions

There is one final and remarkable component to the death of the last caliph and his final wishes.

After Abdulmecid died, the nizam wanted to honour his wish to be buried in India. He ordered the construction of an Ottoman-style mausoleum in Khuldabad, then part of the nizam’s dominions, but now in India’s western Maharashtra State.

Private correspondence between the British authorities shows that in 1946, London took it as fact that Abdulmecid had appointed Mukarram Jah as his heir. It also worried that the succession issue would cause a stir if it became public.

But the British also calculated that the nizam and Azam Jah wanted to keep the plan secret.

Mukarram Jah was still a child. His Indian grandfather was only 60 (he would live for another 20 years). Mukarram Jah would not become the nizam in the foreseeable future - and so the British authorities approved the construction of the mausoleum.

By September 1948, the tomb had been built and a grand door fitted at the entrance, made of carved sheesham wood.

Work on the surrounding complex was about to begin when the Indian army invaded Hyderabad State that same month: it resulted in the deaths of at least 40,000 Muslims and with them, any thoughts of independence from the rest of the country.

Osman Ali Khan, once the world’s richest Muslim, was driven from power. Plans to bring the caliph’s body to India were abandoned. Instead his daughter Princess Durrusehvar appealed several times for the last caliph to be buried in Istanbul. The Turkish government refused.

In 1954 - a decade after his death - Abdulmecid was finally buried in the holy city of Medina, Saudi Arabia.

Buried history and what we know

In every period of history there is much that remains unknowable; so much occurs in private conversations, in unspoken thoughts and feelings, only to be taken to the grave and buried.

I put the idea that Caliph Abdulmecid wanted Hyderabad for a future Islamic caliphate to John Zubrzycki, a historian who interviewed Prince Mukarram Jah in 2005 and wrote his biography.

"Behind his bluster and eccentricities,” he told me, “Osman Ali Khan was a shrewd tactician who wanted to consolidate the legacy of the Asaf Jahi dynasty by cementing an alliance, through marriage, with the exiled Ottoman royalty."

His intention, Zubrzycki said, was to designate his grandson as the caliph of Islam as part of this scheme.

When he met Jah in 2005, he found the elderly prince to be “charismatic and cultured, generous and gentle”, but “saddened by the cards that life had dealt him, thrust by his grandfather into a position of responsibility that he wasn't prepared for and ultimately was unable to fulfil.”

The extraordinary alliance between the Ottoman and Asaf Jahi dynasties in 1931 saw the union of two of Islam’s great houses, of the west and east of the Islamic world.

It helped propel Hyderabad, widely seen as the successor state to the mighty Mughal empire, to the status of a “capital city for all Muslims”, as English Muslim thinker Marmaduke Pickthall described it in 1936.

This matters because when the British left India in 1947, the nizam wanted Hyderabad to be an independent state. If that had happened, then Prince Mukarram Jah and his lineage would have been well placed to claim the caliphal title once he became nizam.

The Indian subcontinent could have become home to the seat of the global caliphate, a centre of prestige and power in the Islamic world. It was not to be. Instead, for decades, this extraordinary history has been consigned to near oblivion.

Where that small piece of inked paper stands in all this is still a mystery.

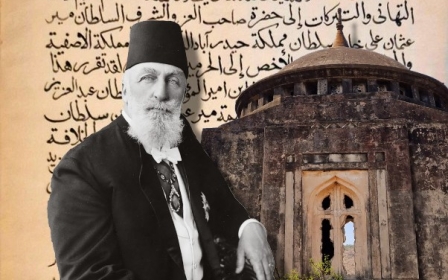

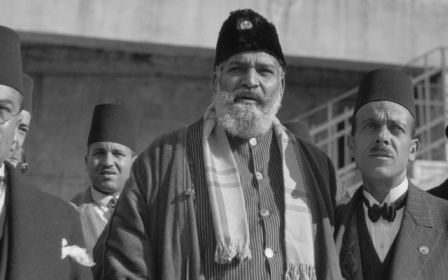

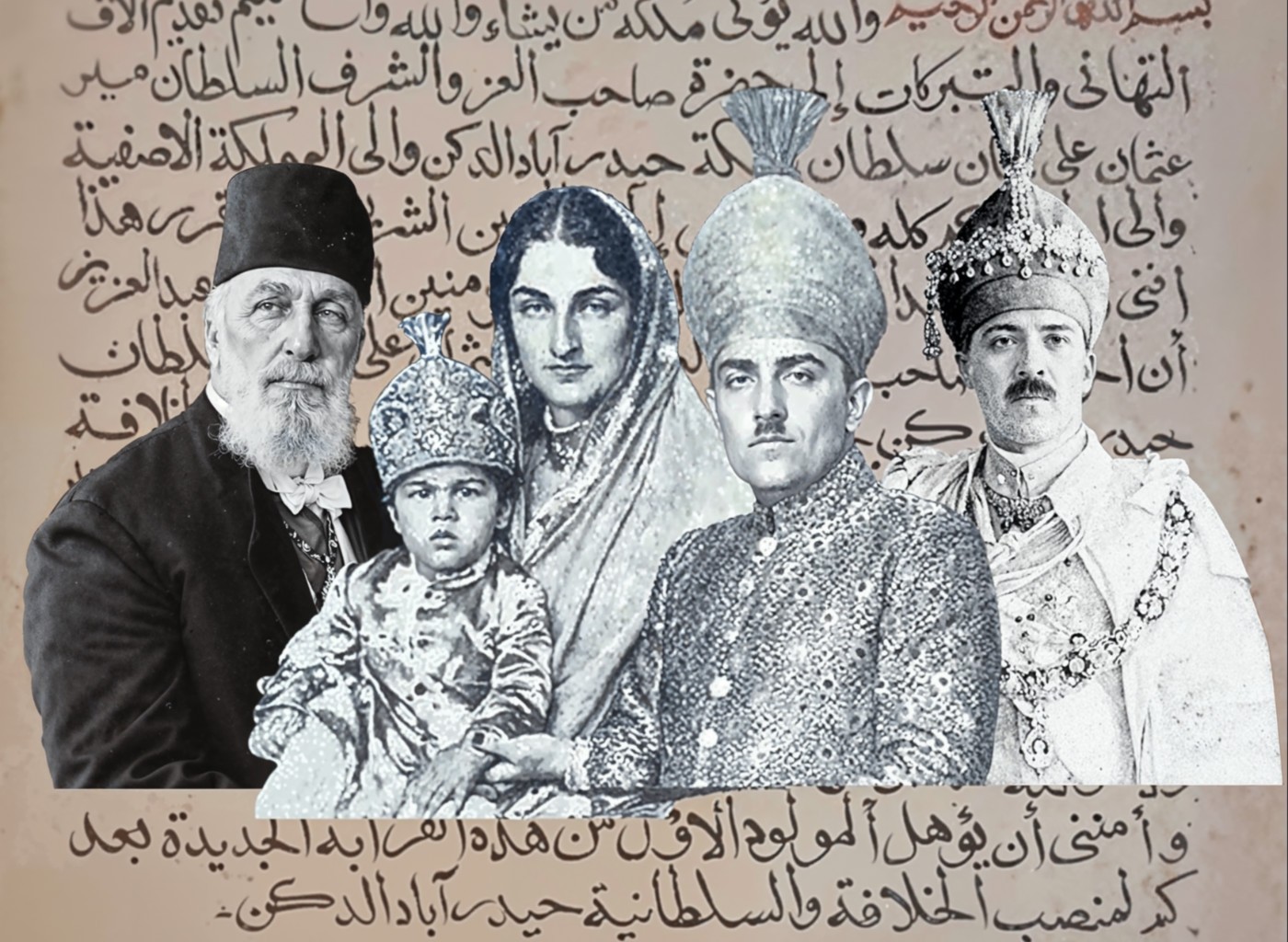

Main photo from left: Caliph Abdulmecid II (1868-1944), Prince Mukarram Jah (1933 – 1968), Princess Durrusehvar (1914 – 2006), Prince Azam Jah (1907 – 1970) and Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan (1886 – 1967). The background is drawn from text from the caliphal deed (Creative Commons).

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.