The oldest man in Gaza: 'Back in the old days, your home was yours'

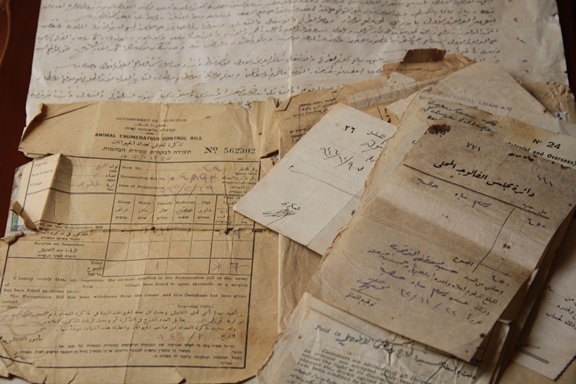

In his youth, Rajab al-Tom, who is believed to be the oldest man in the Gaza Strip, travelled freely through Palestine and Syria on a camel. According to Gaza's Ministry of Health, he is 127 years old. He has witnessed the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the British Mandate, the division of Palestine into three parts (the Gaza Strip under Egyptian rule, the West Bank under Jordanian rule and Jerusalem in the UN's custody), the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 and the rule of the Palestinian Authority followed by that of Hamas.

When he was a young man, al-Tom travelled from Palestine to Syria and Lebanon on his camel. In those days, in the late nineteenth century, the land was named Greater Syria. “I was living in Jabalia city, in the northern Gaza Strip, shopping from Magdala. In the winter I travelled to Beersheba to work as a farmer; in the summer I used to travel to Haifa to see the women I loved,” al-Tom said. “We could move very easily from one city to another; there were no borders between the cities of Palestine or other neighbouring states; wherever I went, I would find freedom and peace,” he told MEE.

Al-Tom used to travel throughout Palestine on foot without any need for a permit, unlike today. “I walked throughout every Palestinian city without seeing a single checkpoint or border crossing; there were no Israeli soldiers to humiliate the Palestinians. Every Friday I used to go to Jerusalem for prayer. Now I need permission from the occupier,” he said with tears in the eyes.

Al-Tom has 300 grandsons, and he spends his time telling them stories of how Palestine used to be. “Back in the old days, your home was yours, your sons were around you, and they had hope for the future. But now it’s different; any minute you could lose it all without any reason,” the old man said.

The year of 1948 is a devastating memory for all Palestinians; some were forced to leave their lands at the threat of being shot, and others kindly gave their land to new refugees who left everything behind and managed to survive. “I saw Jabalia divided into two sections, as hundreds of Palestinian refugees came to make the first refugee camp,” al-Tom said. “Gaza citizens offered everything they could to help them as the United Nations was not able to cover all their needs.”

History is written by the triumphant in the majority of stories we read. It has been that way since the beginning of time and is not unique to one particular race, religion or conflict. For the Palestinians, unwritten history that elders still clearly remember is hazy for the rest of us; those before us witnessed history changing year by year. The stories they relay are not episodes they were taught - they lived them. Before sighs and tears commence, you can see the beaming smiles on the faces of sages when asking about home and a life of peace before the Nakba of 1948.

Palestinian history is passed from one generation to another as elders tell their grandsons the family narratives, who tell their sons and so on. In every refugee house in the Gaza Strip, there are many stories of families forced to leave their homes, neighbours, belongings and in some harsh cases, even their children.

According to UN statistics, 66 percent of historic Palestine’s indigenous people were forced to leave their homes, fleeing to neighbouring states such as Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and of course the Palestinian Gaza Strip. Now, 67 percent of Palestinians in Gaza are refugees who want to return to their homes.

Painful memories

Sadia Tartori, 83, is a Palestinian refugee from al-Faluja village, located some 30 kilometres northeast of Gaza City, just across the modern-day border with Israel. She started by talking about her life in al-Faluja when she was a little girl of 10 years with a lovely smile. She remembers her Jewish friend who was the son of a local goldsmith: “Oh! Abu David, what a kind friend. He used to give me chocolate every time my mother went to his store to buy jewelry; he showed me nothing but love,” Sadia said.

Before the Palestinian Nakba, Muslims, Christians, and Jews were living quite peacefully without any threats. “We were simple farmers and workers who had no need to hold a gun. But [in] the Nakba, groups of Jews started to attack us on our own lands, threatening to kill us if we would not leave. Palestinians defended themselves but what can a stick or a knife do against a gun?” Sadia said.

Sadia was her mother's only daughter and the princess of the family. Her father gave her a tree sapling and named it after her. She planted the seedling in front of her home in al-Faluja.

As a child, Sadia saw scenes that took her innocence away. It took Sadia a long time to prepare herself to recollect her memories of the most difficult period in her life: “I saw the beginning of the rift as new people came to our land and murdered without regret. I saw Palestinian women hiding among the livestock so they would not get raped, I saw young men digging holes in the ground and hiding beneath the earth so they would not get killed and I saw some people throw themselves among the corpses of other Palestinians.” She could hardly speak as her eyes rained. The anguish at these memories was clear in her voice.

“When the war broke out, my mother and I collected all our gold to carry with us. But my father said that it would be a matter of days until we returned. We hid the gold in a jug and buried it. A few days later, I found myself in the Gaza Strip as a refugee. I knew then that I had lost my home.” Sadia said.

Thousands of Palestinians fled to the Gaza Strip after the Nakba, leaving their belongings, thinking they would soon return home. “I arrived to Gaza as many people did, without anything but the clothes I was wearing. For my family, you could say that we were somehow lucky to have relatives in Gaza to embrace our breaking hearts and sorrow, but we were a family that needed to find a way to survive. My mother and I used to go to Khan Younis city in the southern Gaza Strip to get milk and one meal per person each day from the UN. My brothers became fishermen, and grief took my father,” Sadia said.

Sadia’s brother managed to get her a permit from Israel to visit her home later in the 1970s. She was desperately in need of a visit. “I ran toward the location of our home, and the first thing I saw was the seedling I planted, which had become a huge tree, I sat in its shade and I felt peace," Sadia said with a wide smile on her face. “But the feeling vanished when I saw that my home had been demolished.”

Cultural Ministry role in preserving the oral history

The stories that reflect the true events of Palestinian history, the Israeli occupation and life before the Nakba of 1948 must be documented in books for future generations. Yet, the Palestinian Cultural Ministry denies any involvement in collecting oral histories from elders who witnessed these events first-hand.

“The Palestinian Cultural Ministry has no role in preserving oral history,” Mustafa al-Sawaf, the ministry's undersecretary told the MEE. “There are specialised organisations who work on this subject,” he added.

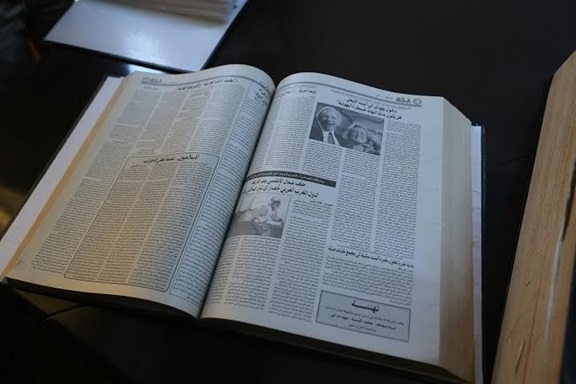

Khaled al-Khalidi, a professor of Palestinian history at the Islamic University in Gaza, and the head of Palestinian Centre for Oral History, told MEE that the centre managed to interview hundreds of Palestinians to convey what they witnessed and endured.

“We started the project in 1999, we broadcasted hundreds of interviews with people who fled their homes and came to Gaza; we interviewed political figures as well like Sheikh Ahmed Yassein in 35 hours of broadcasting,” he said.

Professor al-Khalidi has a great role of preserving Palestinian oral history. “I ask my students to interview elders in the Gaza Strip to bring me new stories as their graduate research paper,” Al-Khalidi said.

Al-Khalidi pointed out how the Nakba was an axial year for Palestinians as he interviewed many of them. He said he noticed how Palestinians turned from rich land owners into people begging for food because of war and occupation.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.