Against Erasure: What a new photo book tells about Palestine before the Nakba

Israel has always tried to hide the story of the Nakba and it's not difficult to understand why. Denial of the Nakba, or "the Catastrophe", allowed the state to propel a myth that its statehood came on an empty strip of land and not atop the ashes of another people.

Around 750,000 Palestinians were uprooted and thousands of others killed over several months between 1948 and 1949.

Despite state-led censorship, the story of their dispossession and exile has persisted.

Palestinians and a small number of Israeli historians have consistently challenged the founding myths of a state built on ethnic cleansing, massacres, and theft of indigenous land.

Whereas the mass expulsion of Palestinians in 1948 may today be considered indisputable in scholarly circles, Zionists, or those who believe in the founding myths of the ethnonationalist Jewish state, continue to undermine accounts of the Nakba.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

These supporters of Israel say that even if Palestinians had existed prior to the state of Israel, they were at most a people without a history. They argue that Palestinians willingly packed up and left, showing that they were not of the land.

But as historians have shown, Palestinians did not willingly pack and leave. Those who left were forced to do so. Many of those who remained were killed for refusing.

The Nakba was the culmination of a process that began with the Balfour Declaration - when the British promised to form a Jewish "homeland" in Palestine in 1917.

Made without consultation with its native Palestinian population, the move paved the way for the destruction and erasure of an entire society with deep roots in the land. A stunning new photo book has the receipts to prove it.

The book, Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine Before The Nakba is collated and authored by Spanish photographer Sandra Barrilaro and journalist Teresa Aranguren.

According to the authors, the project was specifically conceived as a way to create a living memory of Palestinian history prior to the Nakba but also to showcase what was lost as a result of it.

Their work contains a collection of dozens of images from historic Palestine between 1890 and the early 1950s.

'I decided, along with the journalist Teresa Aranguren, to add a grain of sand to the living memory of a people; to the Palestine that existed before the catastrophe, the Nakba'

- Sandra Barrilaro, photographer

"All while familiar with magnificent pre-1948 photo collections such as Walid Khalidi’s Before Their Diaspora, or the work of the erudite Elias Sanbar, The Palestinians, I decided, along with the journalist Teresa Aranguren, to add a grain of sand to the living memory of a people; to the Palestine that existed before the catastrophe, the Nakba," Sandra Barrilaro writes in her introduction.

"In these photographs, time and tragedy provide another layer of meaning. The snapshots that we would discover filled us with wonder, admiration, tenderness, anger - for a lost world, for a people expelled from their lives and their lands. A society rocked by the trauma of expulsion, never to be the same again," she adds.

Sourcing images

The two authors say they were inspired by a Palestinian friend, Soheila Atwan, to pursue the project.

When Atwan put them in touch with the Palestinian historian Johnny Mansour, the duo got access to a treasure trove of unpublished photos culminating in the publication of the first edition of the book in Spanish in 2016.

Many of the photos in the book were sourced from Mansour’s collection, which itself draws from half a dozen other Palestinian families' albums.

Other images were sourced from the US Library of Congress and The G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, amongst others.

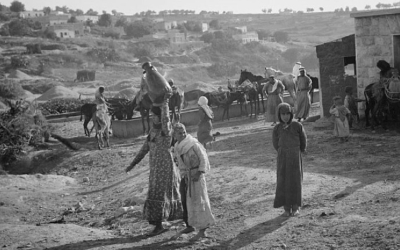

Given the incredibly difficult situation faced by many Palestinians since the establishment of Israel, it's the photographs revealing details of everyday life that are often the most arresting.

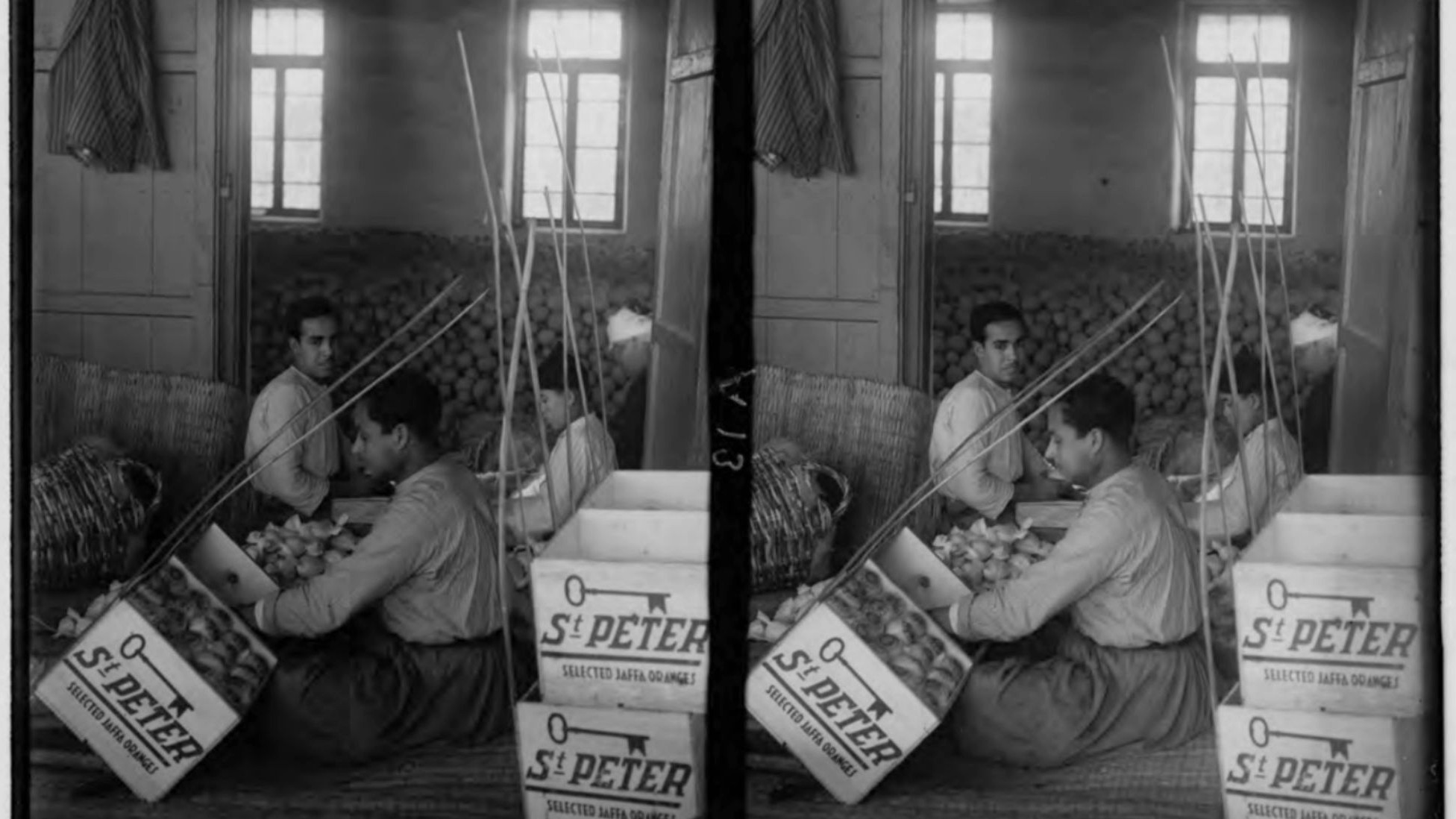

Amongst the first images in the book is a photo of a Palestinian woman pruning an Olive Tree in the early 1900s. A few pages down, another image offers a panoramic view of the city of Jaffa, world-renowned for its orange groves. This is followed by a snap of melon market from the early 1900s.

In a later image, a fish trawler casts his net on the coast alongside Jaffa. In Jerusalem, a shopkeeper selling his ware stares into the camera.

In 1930s Ramallah, a woman conducts her craft at the Women’s Union Workshop.

The book is not just an extraordinary archive of history that counters Israeli myths that linger to this day, it is a stunning tapestry of images depicting Palestinian society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In another image in the book, a mobile eye clinic run by the Palestinian Government Department of Health fits another frame.

Then, a photograph of a school for the blind. On a later page, a doctor and nurse at the women's ward at Hebron’s hospital pose for a still in the 1940s.

'Before times'

In his foreword to the first edition, Pedro Martiinez Montavez describes the book as a radical counter to "intentionally distorted, false, or simply ignorant historiography on the subject".

"It focuses precisely on salvaging and bringing to light many of the roots, the origins, of the Palestinian question," he continues.

"In this book, we encounter the 'before times'; a history kept buried, banished, just as the Palestinians were banished from their land, covering the period between the last decades of the nineteenth century and the middle of the twentieth century.

"It begs the question: is there anything more cruel than the denial of time? This book allows us to visually encounter the idea that time can be recovered and a history that should not have been banished," he adds.

Whereas Against Erasure is the "proof of life" that upends the Israeli myth of “a land without a people for a people without a land”, the book is also a reminder that the search for one's history is never complete.

In his foreword to the new edition, Mohammed el-Kurd reminds readers that while the book is an incredible achievement for the way it celebrates Palestinian society before the establishment of the Israeli regime, it is just as important - if not even more important - to avoid romanticising the era.

“Who was behind these cameras? What can be said about those who lived far from the flashing lights and tape recorders?” Kurd asks.

In other words, though the book’s extraordinary feat may appear to be in the documentation of a life and a society before the Nakba, the questions it poses may be its greatest contribution.

Given that the photographs are sourced from Palestinian families or state archives, each photo is a result, even a feature of the socio-economic context.

Cameras would not have been widely available, and only a certain elite in the towns and cities would have access to them.

So, this raises deeper questions.

If the Israeli administrators had managed to erase those privileged enough to be documented and seen, what might have been the fate of those who lived on the periphery of Palestinian society?

And crucially, how may their memories and their stories be resurrected?

While the photographs are the most powerful part of the book, the authors' commitment to context and attention to detail is really what makes it an outstanding act of political education.

Documenting the Nakba

Throughout it, the authors include short commentary, and at times statistics - like details of orange production or levels of literacy during the 1920s - elevating the level of loss suffered.

Its heavy reliance on the Palestinian bourgeoisie for establishing "proof of life" notwithstanding, the book's ability to take readers on a journey through the changing context in Palestine, as militarisation increases, land takeovers escalate, and Palestinians edge towards expulsion once again, is heartbreaking even for those familiar with the story.

Palestinians are seen being frisked on the streets by British officers in the 1930s as the agitations and the Great Revolt began. Others show Palestinians standing in front of the rubble of their houses in Jaffa, or Hulhul, or Lydda after their demolition by British soldiers.

To see these British tactics in the 1930s being exercised by Israelis on the same population today hits a little differently.

Later, the same Palestinians are seen on trucks as the Nakba takes place.

One image shows a caravan of refugees fleeing Gaza to Hebron in December 1949. Another showcases Palestinian refugees boarding boats to Lebanon and Egypt from Gaza in 1949.

In another, Palestinian refugees are seen at the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp in Lebanon.

At a distribution point in Aqaba, in Jordan, Palestinians collect rations from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).

Given the earlier images of Palestinian children at school, of Palestinian priests outside their churches, of Palestinian women posing outside their villas, of Palestinian journalists broadcasting from their studios, the images of their flight are more chilling.

The book goes on to name 418 Palestinian villages depopulated during the Nakba and either destroyed or taken over. Others say it may have been more than 500.

This brings us to a moment today, in which a genocide of the Palestinians is ongoing, alongside an attempt to gaslight those bearing witness to it.

As Against Erasure illustrates, the attempt to eliminate and expel Palestinians is not new. The obfuscation and denial are not novel, or unique. But a Palestinian memory will always remain, and that should terrify the perpetrators of their suffering most.

Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine Before the Nakba is published by Haymarket Books

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.