Israel’s Likud Troika and the end of the Oslo ‘peace process’

Israel’s relentless accumulation of territorial facts on the ground some years ago doomed the peace process associated with the Oslo Framework of Principles adopted in 1993. It became increasingly difficult to envisage an Israeli willingness to dismantle settlements or remove the separation barrier, and without such steps there could never be achieved a truly independent and viable Palestinian state.

It should be kept in mind, without even raising the issue of the right of return of five million or so Palestinian refugees living outside of Palestine, that the whole premise of Palestinian statehood was based on the green line ceasefire borders that emerged from the 1967 borders.

Even if Israel were persuaded to withdraw from the entirety of occupied Palestine, it would amount to only 22 percent of historic Palestine - less than half of what the UN recommended to a much smaller population by way of partition in 1947 (General Assembly Resolution 181).

For years Israel has played along with the diplomatic consensus built around the two-state solution of the conflict. Israel had lots to gain from upholding this consensus. It could satisfy its own public and world opinion that it was doing everything it could to reach a peaceful end of the conflict. In so doing, Israel gained the time it needed to expand the settlement phenomenon until it became so extensive as to negate any reasonable prospect for substantial reversal.

And yet by relying on its sophisticated control of the media it could pin most of the blame on the Palestinian Authority for one round after another of failed bilateral negotiations. This in turn made it possible to mount a propaganda campaign around the claim that Israel had no Palestinian partner for peace negotiations.

Cynical distraction of Oslo

While this diversionary process continued, Israel consolidated its influence in the US Congress, which strengthened an already unprecedented “special relationship” between the two countries. These dynamics made a mockery of Washington’s claim to be a neutral intermediary. And above all, the consensus pacified the international community, which repeatedly joined the public chorus calling for resumed negotiations. This became a cynical process with diplomats whispering in the corridors of UN buildings that the diplomatic effort to end the conflict was a sham while their governments kept restating their faith in the Oslo approach.

The present futility of Oslo diplomacy has been indirectly acknowledged by Israel, and should be explicitly abandoned by the world community. Whether Israel was ever prepared to accept a Palestinian state remains in doubt. The fact that each prime minister since Oslo - and this includes Yitzhak Rabin - endorsed settlement expansion raises suspicions about Israel’s true intentions, but there were also indications that Tel Aviv earlier had looked with favour upon the diplomatic option provided that it could, with American backroom help, persuade the Palestinians to swallow a one-sided bargain that incorporated the settlement blocs and satisfied Israel’s security goals.

In the last couple of years the veil has been lifted, and it is overdue to declare Oslo diplomacy a failure that has been costly for the Palestinian people and their aspirations.

We can reinforce this assessment by pointing to three connected developments at the pinnacle of Israeli state power, dominated in recent years by the right-wing Likud Party. The first is the election by the Knesset in 2014 of Reuven Rivlin as the 10th Israeli president.

Rivlin is a complex political figure in Likud politics, a party rival of Netanyahu, a longtime advocate of a one-state solution that calls for the annexation of the West Bank, and an opponent of international diplomacy. The complexity arises because Rivlin’s vision is one of humane, democratic participation of the Palestinian population, conferring citizenship based on full equality, and even envisioning an ethnic confederation of the two peoples to be achieved within Israel’s expanded sovereign borders.

Netanyahu's election bomb

The second development was the campaign promise made by Netanyahu on the eve of the March elections that a Palestinian state would never be established so long as he was prime minister. This startling break with the American posture was also a reversion to Netanyahu’s initial opposition to the Oslo Framework, and bitter denunciations of Rabin for embracing a process expected to result in Palestinian statehood.

Netanyahu’s 2015 campaign pledge seemed closer to his true position all along if judged by his behaviour, although contradicting his statement at Bar Ilan University back in 2009 when he declared support for Palestinian statehood as the only way for Israel to achieve peace with security.

To slightly mend relations with Washington after his recent electoral victory, Netanyahu - always crafty - again modified his position, by saying in the heat of the elections that he only meant that no Palestinian state could be established so long as jihadi turmoil in the region persisted.

Given the extent of Israeli territorial encroachments on occupied Palestine, I would trust Netanyahu’s electoral promise much more than his later clarification, a feeble attempt to restore confidence in the special relationship with the United States.

The mask drops

The third development, which should remove the last shred of ambiguity with respect to a diplomatic approach, is the designation of Danny Danon as Israel’s next ambassador at the UN. Danon is a notorious settlement hawk, long an outspoken advocate of West Bank annexation, arrogantly disdaining the arts of diplomacy needed to deflect the hostile UN atmosphere.

If Israel felt that it had anything to gain by maintaining the Oslo illusion, then certainly Danon would not have been the UN pick. There are plenty of Israel diplomats skilled in massaging world public opinion that could have been sent to New York, but this was not the path chosen.

How shall we best understand this Israeli turn toward forthrightness? In the first instance, it reflects the primacy of domestic politics, and a corresponding attitude by Israel’s leaders that it has little need to appease world opinion or accommodate Washington’s insistence that diplomacy, while not now working, remains the only road leading to a peaceful solution.

Furthermore, the Likud troika seems to be converging on a unilateralist approach to the conflict with the Palestinians, while doing its best to distract international attention by exaggerating the threat posed by Iran.

Move to unilateralism

This unilateralist approach can move in two directions: The Netanyahu direction, which is a shade more internationalist, and involves continuing the process of de facto annexation of occupied Palestine, reinforced by an apartheid structure of control over the Palestinian people; the Rivlin/Danon direction of overtly incorporating the West Bank into Israel, and then, either following the democratic and human rights path of treating the two peoples equally, or hardening still further the oppressive regime of discriminatory control established during over 48 years of occupation.

While this Israeli scenario of conflict resolution unfolds, most governments, not sensing an alternative, continue to proclaim their allegiance to a two-state solution despite its manifest disappointments and poor prospects. In effect, "Oslo is dead, long live Oslo."

This see-no-evil posture ignores the emergence of a more promising alternative: the gathering momentum of civil society activism exhibited via the BDS campaign and increasingly acknowledged by Israel as its biggest security threat, leading recently to the establishment of an official Delegitimation Department assigned to do battle with the Palestinian solidarity movement.

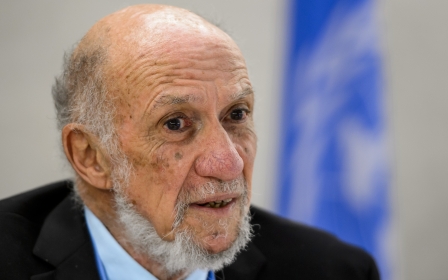

- Richard Falk is an international law and international relations scholar who taught at Princeton University for 40 years. In 2008 he was also appointed by the UN to serve a six-year term as the Special Rapporteur on Palestinian human rights

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Palestinians walk amid the debris of house belonging to Abu Heycaa family after Israeli forces destroyed it on 1 September, 2015 in Jenin province of West Bank. (AA)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.