Dinosaurs and ancient beliefs: Life in Libya's highlands

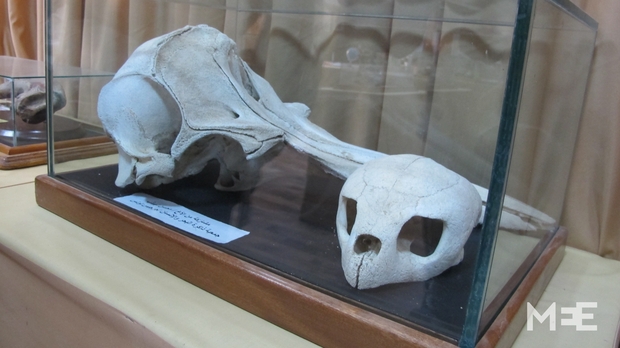

The farmers simply couldn't get over it. Everybody agreed: those bones were far too large to belong to a cow. It was 1998 when the first dinosaur remains were discovered in Libya and it was in this remote mountain village in the northwest of the country where they were found.

Halit Yarro, one of the two employees who works in shifts at Nalut's museum of dinosaurs, tells us more about Libya's first inhabitants.

'Ours is the only dinosaur museum in the whole of Libya, not even Tunisia has one'

- Halit Yarro

"Ours is the only dinosaur museum in the whole of Libya, not even Tunisia has one," 46 year-old Naluti points out proudly, just before offering a guided tour across the exhibition. Fossilised remains of trees, crocodiles, sharks and, of course, the dinosaur bones found less than one kilometre from here, are all on display in the tiny museum's single room.

"In 2005, a team of American researchers determined that the dinosaurs they belonged to were 15 meters long and weighed 8,000 kilograms,” explains Yerro, standing by a framed printing of the beast in question.

The museum is located in downtown Nalut, at 600 meters above sea level and about 60 kilometres from the Tunisian border. Local estimates point out that only half of its population of 30,000 still remains in what is one of the main locations in the Nafusa mountain range.

Nalut is also an outsider in Libya because the majority of the people living here are Amazigh. Also known as Berbers (which is a term some find offensive), the Amazigh are native inhabitants of North Africa, with a population extending from Morocco's Atlantic coast to the west bank of the Nile in Egypt. The Touareg tribes in the interior of the Sahara desert share the same ancient language.

However, the arrival of the Arabs in the region in the seventh century was the beginning of a slow yet gradual process of Arabisation. Today, unofficial estimates put the number of Amazighs in Libya up to almost 600,000, about 10 percent of the total population.

Lessons from war

After decades of extreme marginalisation under Muammar Gaddafi and given the growing instability in the country, Libya's largest minority is uniting under the so-called Amazigh Supreme Council. It's an umbrella organisation for the 10 main Berber locations. Kaire Ben Taleb was elected as the representative of Nalut on 30 August, in a pioneering election process that allocated a 50 percent representation quota for women.

"After the war we learned a lot," says Ben Taleb. "We ousted Gaddafi only to discover that we would still have to cope with the same totalitarian mentality for years to come," he explained.

Nalut's main representative stresses that the Amazigh share no ideological affinity with either of the two governments in Libya - one based in Tripoli and another in the city of Tobruk, 1,200 kilometres east of the capital.

'We ousted Gaddafi only to discover that we would still have to cope with the same totalitarian mentality for years to come'

- Kaire Ben Taleb

“We were pushed to one side with Tripoli but we are fully aware that we have no share in this battle between Islamists and Arab nationalists,” underlines Ben Taleb.

For the time being, each and every community in Libya has been forced to take sides, so travelling overland across the country involves avoiding areas under the control of rival militias by taking gruelling by-pass roads, or even crossing into neighbouring Tunisia, only to enter the country again from another border post. Ben Taleb points to “tacit pacts” as a way to ease communications.

"People in Zintan - an Arab enclave in Nafusa close to Tobruk - know that if they want to go to Tunisia they have to let us travel to Tripoli across their territory. In the worst-case scenario they'll take hostages but we'll follow suit until we get to exchange them in Kabaw, a village halfway,” he elaborated.

Nalut looks quiet so nothing prevents us from accepting Ben Taleb's invitation for a walk around town. Right on the roundabout that manages the traffic towards the valley, a group of workers strive to settle the base that will support a sculpture of the iconic last letter of the Amazigh alphabet, which also represents freedom.

A mere 50 metres from the spot, the rubble of the house of Sheikh Omar Naami, a prominent Ibadi leader executed by Gaddafi in 1984, remains uncollected as yet another reminder of Gaddafi's grip on the Amazigh. Apparently, they were not only slighted and discriminated against for not being Arabs, but also for being followers of Ibadism, a branch of Islam which is neither Sunni nor Shiite.

Isa Omar Naami, a nephew of the revered sheikh and a volunteer at Nalut's radio station, lives in a nearby house. He admits things have changed for the better for them, but he fears new threats for his long-neglected community.

'Radical Islam is spreading like wildfire all over Libya and we, as non-Arabs and non-Sunnis, might well be their next target'

- Isa Omar Naami

“Radical Islam is spreading like wildfire all over Libya and we, as non-Arabs and non-Sunnis, might well be their next target,” warns Naami.

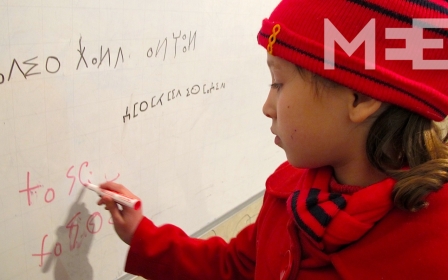

Against all odds, Nafusa has been witnessing a surfacing of the long-neglected denomination over the last four years. Ibadi schools have popped up all across the mountain range since 2011. Moreover, Nalutis proudly claim to host the only Ibadi high school in Libya.

It's lunchtime so Ben Taleb takes us to the town's Turkish restaurant, another focal point in Nalut. It was set up in 2013 by Suleiman Dogan, a Turk from Antakia who found Nalut a place “as good as anywhere else in Libya” to run his own business.

Actually, Nalut is mourning the recent loss of a regular client at Dogan's place. Abdu Saat Abdu's story is well known all over Nafusa, although it was also far from being the only one of its kind. This local peasant had taught himself English with the aid of a dictionary and an adventure novel that a group of American visitors to the citadel handed him in the late 70s. The brief contact with foreigners raised the suspicions of Gaddafi's security apparatus and Abdu ended up spending 18 years in jail.

"I was not told that I had been imprisoned for being a spy until the sixth year in prison," Abdu had told this reporter back in 2011.

Citadel of the centuries

Despite the restrictions on entering the country, the imposing citadel of Nalut has always been a magnet for archaeologists and historians. Built in the 11th century, it stills rises majestically over the valley.

"It is not a king's castle but a fortress where each family would keep food in their own chambers to be able to survive the frequent wars in the area,” Ben Taleb stresses from one of the castle's old mills.

The citadel was abandoned in the 1960s but it's hosting new guests now. Its old grain stores are today home to the myriad of sub-Saharan migrants that stand in line along the main road, waiting for an occasional job in construction.

'The tank replaced the statue of the dinosaur we had before because the elders said it was a pagan symbol that chased away the rain'-

- Halit Yarro

Salif, a 21-year-old Malian, admits that Nalut is just a stopover on his way to Europe. On a good day of work, he explains, he can make up to 15 Libyan dinars - around $5, but he'll need to save $600 to be able to jump on a raft to Europe.

The majority of these young men have probably wondered about the white tank overlooking the valley from a base, just a few metres away from where they wait in line. Its cannon muzzle, blocked by an iron dove carrying an olive branch, gives a clue, but we don't get to know all the details until we're back at the museum.

"The tank replaced the statue of the dinosaur we had before because the elders said it was a pagan symbol that chased away the rain," recalls Halit Yarro, while the muezzin calls for the evening prayer from the mosque nearby.

Before we leave, Yarro gives us a bag of toy dinosaurs as a souvenir before asking us to sign on the visitor's book. We check who the previous guests were the week before. It was group of boy scouts from Benghazi, the city in Libya where the fighting is most intense.

"It's difficult to believe, isn't it?" says the museum keeper. “But life goes on in Libya after all.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.