Palestine still just dotted lines on map as Google passes the buck

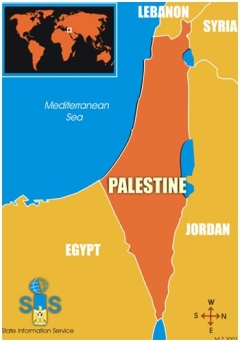

If you do a search for Palestine on Google Maps, you will be taken to a map of Israel. There is no place called "Palestine" displayed.

Without a name on the map, in the digital realm, a country or state becomes invisible. Political “logo” maps - those that give a name to the contours of a nation - have an important function, however: they can encourage a sense of national belonging in its people.

Palestine (including the Gaza Strip and the West Bank) is one such “non-place” with only a tenuous existence. And in a digital age, the struggle over its territorial recognition has increasingly moved online. For many, there is a lot at stake – digital recognition of Palestine as a territorial entity could precede territorial recognition on the ground.

Indeed, in 2003, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the organisation responsible for overseeing the namespaces on the internet, gave Palestine its own web domain of .ps. In May 2013, after the UN recognised Palestine as a non-member observer state, the name of its landing page changed to Google Palestine from Google Palestinian Territories. For Palestinian activists, such virtual recognition was a step in the right direction, while Israeli government officials condemned it as an impediment to peace. Yet while Palestine has made some headway in getting some virtual recognition, it still remains under-recognised on many digital platforms, including unofficial web spaces such as Web 2.0.

Such a lack of standardisation is not surprising – there are, after all, no transnational cartographic standards that are consistently invoked. Instead the contours and content of maps are a mapmaker’s pejorative, subject not only to politics, but also to the resources and data available.

For instance, detailed coordinates of many places in Palestine are still missing, as even the worlds’ largest geographic data source, Google Maps, receives its data - including place names and borders - from a combination of third-party providers and public sources.

With Israeli cartographic companies providing most of the source material on the region and Palestinian cartographic institutions unable to compete in the map market, Palestinian geo-coded data and information is scant. Palestine remains underrepresented on most web-based mapping platforms, although activist appeals to digital platform administrators to include Palestine and Palestinian data have made some gains towards more virtual recognition.

So when the story unfolded that Google had apparently erased Palestine from its maps and an online petition gained over 320,000 signatures to put it back, it hardly mattered that the rumour of Palestine’s cartographic erasure on 25 July turned out to be no more than just that: a rumour.

Anonymous lines on a map

What does matter, however, is that Palestine was never labelled in Google Maps in the first place. Instead, dotted lines have long delineated the territorial boundaries of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

With these territories mostly unidentified and the legal status of the dotted lines undefined, the lack of visual and textual information “passes the buck" to viewers, as only those with specialised knowledge would know how to interpret the lines.

Maps are therefore always political as they are inevitably selective: they include as much as they exclude

There are many territorial disputes around the globe, ranging from Crimea to contested islands between Korea and Japan, to Palestine. Google Maps attempts to stay out of such geopolitical disputes by either showing different maps of the contested territories, depending on the locality of the search engine so as to cater to local users (for Russians, for instance, Crimea appears as part of Russia, but not so for Ukrainians), or by eliminating contextual information and putting maps into a “vacuum”.

Maps are therefore always political as they are inevitably selective: they include as much as they exclude. When it comes to mapping contested territories, Google’s market logic can therefore not supersede the logic of politics.

Whether changing the maps for different audiences or by doing simply what mapmakers do – select, include and omit certain cartographic features and data points - maps are politics by other means. This is especially true when it comes to long-simmering territorial disputes.

And that's why Google Maps’ apparent cartographic elimination of Palestine could ignite a “map war” and become a powerful political symbol for those who still have only a very tenuous existence on the worlds’ maps.

- Dr Christine Leuenberger, Cornell University (USA), has published widely in various academic journals, books and popular news outlets. She is currently working on the social impact of hard and soft borders and barriers, the history and sociology of the human sciences in the Middle East, as well as on peace and educational initiatives in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa. She has served as a Fulbright Scholar, a Fulbright Specialist, and as an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science & Technology Policy Fellow. She has also been the recipient of a National Science Foundation Scholar’s award to investigate the history and sociology of mapping practices in Israel and the Palestinian Territories.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Palestinian man finds shade under a blanket and a map of Israel and the Palestinian Territories as he walks over the rubble of what used to be a family home, in the Shejaiya neighbourhood of Gaza City, in August 2014 (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.