'No, na, hayir!' Turks in Britain vote in presidential referendum

LONDON - In the run up to Turkey’s seminal 16 April referendum that could see massive constitutional changes enhancing the president's powers, Turks in the diaspora have been travelling to various consulates and polling centres to cast their votes across Europe.

While the French and German diasporas have been largely supportive of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development party (AKP) and are thus expected to deliver a Yes vote, the UK’s Turkish community have been the biggest supporters of the left-wing, pro-Kurdish opposition and are expected to be swing behind the No vote.

In the November 2015 parliamentary elections, the UK was the only country where the majority of the diaspora supported the People's Democratic Party (HDP), with 54 percent voting for them.

One reason for this is that while the five million or so Turks who make up the diaspora in Germany are composed largely of economic migrants, the UK’s Turkish population - which numbers roughly 150,000 without counting Turkish Cypriots - is heavily dominated by political refugees and their families.

As such, there did seem to be little sympathy on display for the proposed constitutional changes or Erdogan, when voting began at the Novotel in the London Borough of Hammersmith on Thursday.

Irfan, a trade unionist who left Turkey after facing “political problems” in the country 18 years ago, was adamant in his position.

“No, na, hayir!” he said, showing his opposition to the referendum in English, Kurdish and Turkish.

“They want a dictatorship. We had a one-hundred-year republic - but he wants it like the Ottomans,” he said.

“I live in England - even this bourgeois democracy is better than dictatorship!”

For two other voters, the prospect of a Yes victory in the referendum poll was unbearable.

“He’s already so powerful - we don’t want him to get more powerful,” said one, who declined to give his name.

“We don’t want to think about it!” his friend agreed.

Hassan, from Oxford, said that he was voting to prevent Erdogan becoming a “dictator”, perhaps the term most commonly cited by No voters.

“The power is going to be in one hand - this is really dangerous,” he said. “It is going to be more than a monarchy. That’s why we don’t want it - we want a democracy and that’s why we have to say No.”

'Anyone' can be a target

Large numbers turned out to vote at the hotel in west London to vote - various organisations in the diaspora, keen to get as large a turnout as possible in lieu of such a seminal poll, hired buses and minivans to transport voters from various disparate locations to the venue.

Voting in the UK begins on Thursday and lasts four days until Sunday. This stands in contrasts to most other countries in Europe, where voting for the diaspora opened on 27 March and lasts until 9 April.

While the Turkish population of the UK is significantly smaller than in Germany or France, it is roughly the same as Switzerland and larger than Denmark’s - leading some No campaigners to cry foul.

“We believe the AKP is trying to make it difficult to vote in the UK because they know they are the third party,” said Feyzullah Cinpolat, one of the leading No platform activists.

“There should be other voting points in the Midlands and the North. People now have to come down from all over England and Wales to vote. I know personally, many people, they work and say it is not possible to come down to vote.”

He also criticised Turkey's Supreme Election Council (YSK), which is responsible for organising elections both inside and outside the country.

“It should be an independent body, but it is - like any other organisation - an ally of the government,” he said.

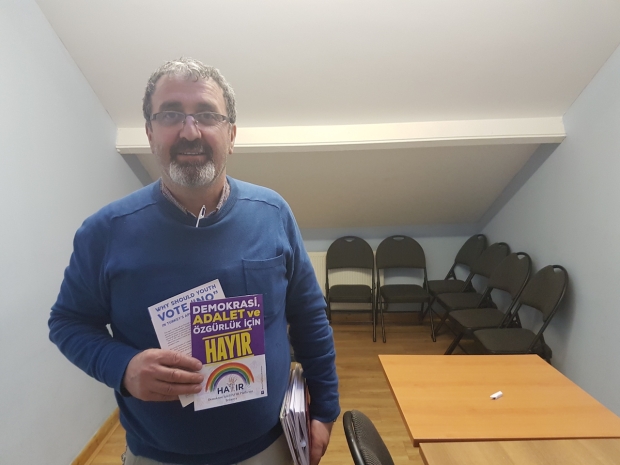

MEE met Cinpolat in the North London Community House, one of several hubs in north London used by the city’s Turkish and Kurdish community for social and political gatherings.

Cafe Life, which adjoins the building, is covered in left-wing Turkish and Kurdish paraphernalia, including photos of the Deniz Gezmis, the “Turkish Che Guevara” who was executed in 1972 following that decade’s military coup and who has become a symbol for the Turkish left.

Cinpolat has seen his fair share of political upheaval. As a member of the Revolutionary Communist Party of Turkey (TDKP), he was imprisoned following the 1980 coup by the deeply anti-communist military junta.

After being freed he found the repressive atmosphere stifling and was unable to continue his political activities due to harassment from the government. As a result, he left to live in the UK, though he has returned to visit family during periods of political liberalisation in the country.

However, despite the hardships he faced during the authoritarian rule of the generals in Turkey, Cinpolat believes the current conditions in Turkey are even worse.

“It is much heavier now,” he explained. “At that time there was pressure on certain political groups and you knew which people were the target of the government - now, everyone is the government’s target and the scale of the government’s attacks are larger.

“Anyone can be the government’s target at the moment.”

More than 41,000 people in Turkey have been arrested since a failed coup attempt in July, as well as 100,000 fired or suspended from their jobs.

No campaigners say a Yes victory could see the even greater repression, while government supporters argue the crackdown is necessary to tackle “terrorist” groups like the PKK, Islamic State and the Gulen movement that they blame for the July coup attempt.

Power for the public

There were also a few Yes supporters among the crowd in Hammersmith. Most felt their position had been misrepresented both by the No campaign and the media both inside and outside Turkey - approaching one table of Yes supporters, one activist asked, “Is he from BBC? Don’t trust the BBC!”

Izzet, from Wimbledon, said he would be voting Yes and criticised the No voters who had characterised the referendum as a vote for dictatorship.

“Have they read the current legislation? It is not helping a dictatorship. They are supporting the dictatorship!”

He argued that the constitutional changes, far from undermining democracy, were ultimately about breaking the hold of the state “bureaucracy” which has stood in the way of Turkish democratic aspirations.

“They made the coup in 1960, they did it in 1980 and then they just did it on 15 July. Again, again, again. All these people are not elected - for the first time in our history the public will have the power.”

Izzet wore on his lapel the badge of the Union of European Turkish Democrats (UETD), a transnational organisation which is ostensibly non-partisan, but which is described by some as “Erdogan’s European lobby group”, a characterisation the group rejects.

Turhan Ozan, UK chair of the UETD and a former Liberal Democrat parliamentary candidate in north London, was present as an observer for the Yes camp in Hammersmith, albeit not wearing his UETD cap.

"UETD is not a party-political organisation, but many members of UETD are supportive of the Yes campaign and they are actively campaigning for Yes in the UK," he explained.

He argued the constitutional changes, which will see the role of prime minister abolished, were about resolving an inherent dispute between the presidency and the executive.

"The current constitution [that] Turkey is managed by was created by the [1980] military coup and they created a system where the president is very powerful, but not accountable [to] the public," he explained.

He said the current division of power between the two offices of state would in future lead to political gridlock over who would take decisions in the country.

Despite his enthusiasm for the changes, however, Ozan conceded he was fighting an uphill battle in his home turf.

"Yes will not win in the UK, no," he said. "We had four elections here and opposition parties are stronger in the UK - but we have to give the choice to the people."

Avoiding tensions

One point that both camps agreed on is that the UK has seen little of the violence and animosity that has broken out elsewhere in Europe.

In Brussels, on 31 March, a number of people were hospitalised after a stabbing attack while Turks in Belgium queued to vote, while Germany has seen regular bouts of violence between Turkish and Kurds. Meanwhile, the decision of the Dutch government not to allow Turkish ministers to speak in favour of the Yes campaign led to clashes on the street and a collapse in relations between the two countries.

Conversely, the UK - which still maintains the strongest bilateral relations with Turkey despite the Brexit vote - has been relatively calm and peaceful, though political tensions still remain.

Polls in Turkey are notoriously unreliable and though recent indicators have suggested a Yes victory, few believe that Turkey's future is yet written in stone. Though the Turkish population in the UK is small and lacks the power to swing the election that the German diaspora has, voters still want to make sure they are able to have their say on the future of Turkey.

"We are really happy for the chance to choose the future for our children," said one voter, Guney, originally from Istanbul.

"We don't want to follow only one person...if we all come together then obviously it's not going to be allowed."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.