The biting satire of Libya's pop-art scene comes to London

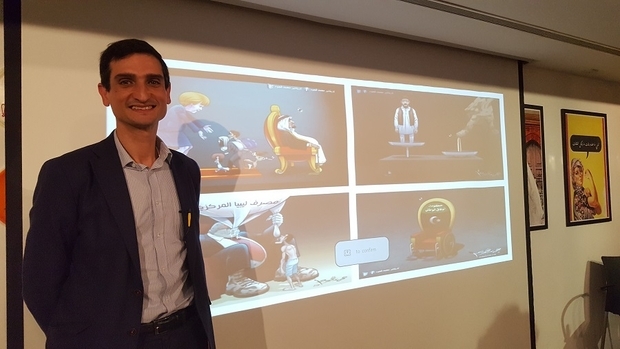

LONDON - Libyan writer Ghazi Gheblawi recently talked about the history of satirical cartoons and their relationship to modern art forms in Libya as part of the Pop-Art from North Africa exhibition at London's P21 Gallery.

The show, which is open until 4 November, features a striking collection of works ranging from paintings to digitally manipulated images, music, animation and street art.

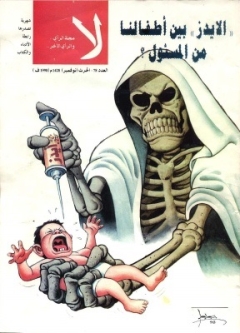

It is an angry reference to a scandal that rocked Libyan society to its core in the late 1990s. More than 400 children were infected with HIV in al-Fateh children's hospital in Benghazi.

When details of the contamination began to emerge, Gaddafi’s government was quick to try cover up the story. Husbands were told to have their wives checked, implicitly suggesting that they were the source of the infection.

In a rare instance of defiance, families stormed the hospital and staged protests, calling for an investigation and demanding the details of what had happened. Fearing the stigma, many families chose to remain quiet, while others went public with their pleas for help.

Faced with public anger, the government tried to appease the families and sent the children affected abroad for treatment. Criticism of the hospital, however, was not allowed, and five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian intern shouldered the blame entirely. They were sentenced to death by a firing squad before a deal with the EU secured their release.

Hasan Dhaimish, known as Alsatoor, "the cleaver," similarly changed Libya’s political art scene. “He cleaved and chopped, no one was safe from him,” Gheblawi explained.

Alsatoor is remembered for his piercing commentary on the harsh reality of Libyan life and unapologetically holding politicians up to scrutiny regardless of state censorship.

Alsatoor migrated to Britain in 1975 and settled in Burnley, a post-industrial town in the north. At the time, he was not interested in political activism. However, a trip to London changed that when a Libyan opposition magazine caught his eye. He contacted the magazine and started publishing satirical cartoons, and thus began his foray into the public sphere.

“It is the Libyan people’s responsibility to liquidate crazy Gaddafi," Alsatoor wrote in text accompanying a caricature of Gaddafi in response to the deposed Libyan president's statement: "It is the Libyan people’s responsibility to liquidate such scum who are distorting Libya’s image abroad.”

Gaddafi was the longest-serving leader in both Africa and the Arab world, having ruled Libya for 41 years before he was killed. He was seen being mocked, beaten and abused before he died.

In May 2011, the International Criminal Court's prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, sought the arrest of the Libyan leader for "widespread and systematic attacks" on civilians.

Alsatoor remained unknown beyond the persona he created, and despite the Gaddafi government's best attempts, they were unable to identify him. Libyan dissidents were labelled "stray dogs" by Gaddafi, and assassination squads were sent after them around the world. During this period, Amnesty International listed 25 such killings, but Alsatoor was not identified.

It is the Libyan people’s responsibility to liquidate crazy Gaddafi

- Hasan Dhaimish, artist

The growth of the internet and the tools it made available meant that Alsatoor was able to be innovative. “He was technologically sound and used different mediums like gifs, animations, videos. Think - a comic strip but in gif form!”

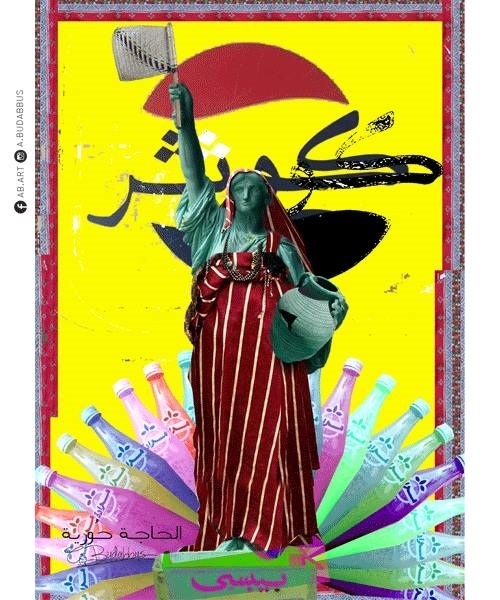

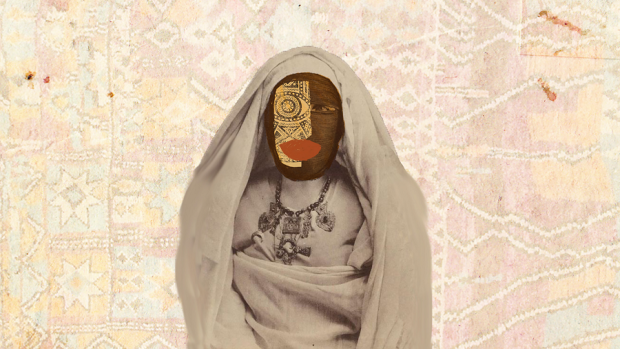

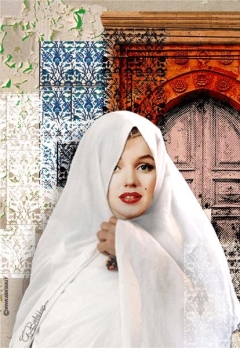

Today, with the internet and increasing globalisation, we are introduced to the likes of modern artists such as Alla Abudabbus and Malak Elghuel. Abudabbus’s bold commentary tackles the Libyan mindset with wit and irony while fusing traditional artefacts.

But satirical art has not been confined to cartoons. More recent adaptations can be seen in Libyan street art. Elements from both Zwawi and Alsatoor can be found in the modern street art that emerged after the Libyan revolution began in 2011. Some of the earliest revolutionary street art was produced by the cartoonist Kais al-Hilali.

"Gaddafi calls himself the king of kings of Africa; I say he’s the monkey of monkeys of Africa," al-Hilali said in an interview with the French TV channel TF1 before he was killed in March 2011. One of his most iconic images depicts Gaddafi as a monkey.

According his mother, the 34-year-old was shot dead on his way home, after drawing a caricature of Gaddafi on a wall in Benghazi.

But Libya's satirical cartoonists also push against political correctness. A cartoon depicting the Government of National Accord as a disabled person draws an uneasy response. “Surely, to depict incompetence as a disability is offensive?” a member of the audience said. “People are not yet educated on rights and lack a sense of sensitivity," he added.

Featuring more than 15 artists from North Africa, the exhibition brings together work inspired by the pop art form and celebrates local identity. It looks at the interplay between imported Western culture and indigenous art forms and the dialogue between the two.

“The exhibition hopes to challenge dominant misconceptions of a region in crisis,” the curator, Najlaa al-Ageli, told MEE. “We hoped that by sharing this collection, we can offer a unique insight into one of the planet’s most vibrant and diverse areas, away from the two-dimensional stories that dominate the media.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.