The price of peace? How Damascus strikes deals with beaten rebels

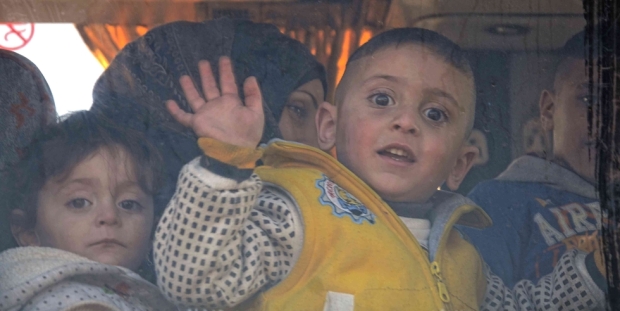

Ahmed Hamid remembers the exact date, 25 April this year, when he and his extended family abandoned their homes in Al-Waer, a dusty modern town just outside the central Syrian city of Homs, and piled into green government-supplied buses.

It was a traumatic moment. Al-Waer was under rebel control but on the verge of surrender to the government army. No one knew for sure whether they were making the right decision to accept the promises of safe passage out of it.

Was it more dangerous to stay or go?

Their 11-year-old son, Omar, had been struck by a mortar and killed while playing in the street during the early part of the war, he added. “Everything bad happened here because of the rebels who came here,” Hamid later recalled.

“That was the reason. I don’t know where they came from. I had no contact with them. They never asked me to join them,” he said.

The government plan

My ministry of information escorts were willing to drive me through all three districts which government planes had bombed. Al-Waer was noticeably less devastated than the other two neighbourhoods.

Nor was the siege of Al-Waer total. People who before the war had jobs in the bakery just across the frontline in the government-held area told me they were now allowed to walk to work back and forth through checkpoints.

Kebab-stall owners could get meat from the government side provided they paid the checkpoint operators a bribe. Teachers could cross to their schools. But life was precarious and there was no prospect of change or relief.

The government’s strategy was collective punishment, aimed at trying to get civilians to press the armed fighters to give up.At the end of last year, the rebels and the government started to negotiate. It took a long time. There were several false starts, partly because at least four rebel groups operated in Al-Waer and it was hard to get them all to agree, according to a Syrian government source.

If the siege was lifted, the government said, the rebels would be bussed to Idlib or Jarablus close to the Turkish border, even allowed to take their rifles and side-arms with them. Their families and other civilians could go as well.

The government strategy was clear: bottle the rebels and their supporters up in peripheral areas of Syria rather than have them in the central north-south heartland which stretches from Damascus to Aleppo.

The alternative offer to the rebels was to stay in Al-Waer and be screened for conscription into the government army. Every male between 18 and 41 is liable for service.

The government strategy was clear: bottle the rebels and their supporters up in peripheral areas of Syria

Each man within that age group who had not already served as a soldier would be individually checked as part of the deal. He would have to sign a taswiya (a settlement) confirming his decision either to join up or seek exemption by proving he was entering higher education.

Yet there was a huge vacuum of trust, not least from the rebels, who knew that the government had detained tens of thousands of activists since the war began.

Human rights groups including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have accused the Syrian government of widespread human rights abuses, including illegal detentions, torture and unlawful killings.

Amnesty earlier this year reported that up to 13,000 people considered to be opponents of the government had been hanged at the Saydnaya military prison in the first five years of the war. It also said that an estimated 17,000 people had died in prisons across Syria as a result of inhuman conditions and torture since 2011.

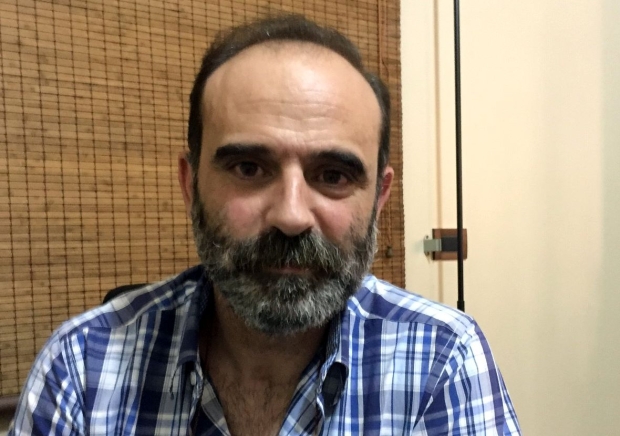

Elia Samman, an adviser to the Ministry of National Reconciliation, acknowledged that the government has detained tens of thousands of people in security sweeps in government-held towns and cities for political activism or alleged pro-rebel actions, though not as part of the reconciliation agreements.

He told MEE the ministry takes up many of their cases and over 70,000 detainees had been released by September this year.

In the case of the Al-Waer arrangement it took Russian involvement before it was agreed in March this year, Samman said. Rebels and civilians were more willing to accept assurances of safe passage from Russian military police than from the government army.

Rebels loyal to the al Qaeda-affiliate Hayat Tahrir al Sham (previously Jabhat al Nusra) and to the Muslim Brothers went to Idlib. Men with Ahrar al-Sham and Jaish al-Islam went to Jarablus. Several thousand people made the journey.

Why we wanted to come home

Sitting on a plastic chair on the shady side of the street opposite his damaged home, Ahmed Hamid, 42, took up the story. His wife emerged with some of their children while we talked.

“When we got to Jarablus, we were put into tents to live. I hadn’t wanted to leave Al-Waer but my wife and father insisted. They were afraid for the children. I was thinking logically but she’s emotional,” he told me.

“The rebels had told us they [the government forces] were going to kill us and take revenge if we stayed in Al-Waer,” she said.

She rang her elderly parents who had remained in the neighbourhood, and was told everything was fine. “When I saw the rebels had been lying, we decided to come back,” she said.

Nujud and her husband were not alone in wanting to come home. The Syrian Arab Red Crescent helped around 650 people returned by bus to Al-Waer from Idlib and Jarablus.

Hamid and his wife brought their small children but their 16-year-old son stayed in the camp along with Hamid’s father and his three brothers. They did not want to join the Syrian army.

In a second-floor flat in a nearby street, Muraya Nasr al-Methoud offered me coffee in the traditional Syrian way. The Homs area is more conservative than Damascus and, like most women in al Waer, she wore a long black abaya. The windows of her flat were all blown out, the holes covered in pieces of plastic sheeting nailed to the wall.

When the offer came this spring to leave Al-Waer, she stayed but her three married sons in their late twenties and early thirties went to Jarablus. “They were told something bad would happen to men who stayed here,” she told me, “but when they saw it was wrong they came back.”

They have since joined the Syrian army. She knows their locations. All are in different parts of the country but she has regular phone contact.

They were told something bad would happen to men who stayed here, but when they saw it was wrong they came back

- Muraya Nasr al Methoud

My interviews were conducted through an interpreter from the Ministry of Information, but I picked the interviewees at random while walking through Al-Waer. Their answers had the ring of truth, except when I asked whether they or their relatives had supported or helped the rebels. At that point their answers usually became vague.

“The rebels never forced anyone to join them,” al-Methoud said, “but I didn’t want my sons to go with them. Their friends might press them to so I tried to persuade them to stay inside as much as possible. I’m a government employee. I work in the bakery, so I told them ‘How can you join the rebels?’”

She seemed to be afraid that she would be sacked or punished if the government knew she had sons working or fighting with the rebels.

How the deal spread

The Al-Waer deal has been replicated in dozens of locations across Syria during the last two years.

Described officially as “reconciliation” agreements, they are creating pockets of peace in various parts of the country and changing the face of Syria’s six-year war.

The idea came from a small opposition party, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), whose leader Ali Haider was appointed minister of national reconciliation soon after the crisis began in 2011.

The SSNP took it to Riad Hijab, the then-prime minister, who later defected and now heads the exiled opposition’s High Negotiations Committee. He turned it down.

Some months later President Bashar al Assad developed the idea. He made it a cornerstone of his strategy of putting opposition-held areas under pressure through bombing, siege - or both.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee has described any deal through which people are forced to evacuate an area as a war crime

Critics call the reconciliation agreements “surrenders” and the United Nations Human Rights Committee has described as a war crime any deal through which people are forced to evacuate an area.

Media reports, based on opposition sources, often claim the deals are forced evacuations. But in all but a few cases, civilians have had the option to choose whether to stay or go.

Reluctant to surrender, rebels and their supporters among opposition propaganda outlets have said those who give up will either be detained or killed, and that this has happened.

Government sources say the security forces would be undermining the strategy of negotiating surrenders if rebels were executed or detained.

Pacification? Unpopular with commanders

“Some agreements have broken down but there are 103 sustained reconciliations which have worked and are surviving completely,” said Samman, the adviser to Haider who is also a senior member of the SSNP.

“They have affected the lives of two million Syrian citizens, who have returned to their normal productive lives.

People are often anxious about being interrogated. Samman said the process usually lasts for about half an hour.

“The questions are not about what a person did in rebel areas, but about what kind of weapons the rebels had, who supplied them and where they came from. No one is arrested.”

There is no uniform pattern to the agreements. Sometimes they are negotiated by the Ministry of National Reconciliation, sometimes by the Bureau of National Security, which co-ordinates between the various security agencies. Sometimes local community or tribal leaders (muftars) are involved. In every case, people get an official document regularising their status.

I remember a colonel telling me: ‘You’re worse than the terrorists. We fight but you give them a chance.'

- Elia Samman, senior member of the SSNP

The agreements provide for no genuine reconciliation in the sense of opposing forces meeting each other half-way and trying to understand the other side’s grievances. They offer nothing more than amnesty in return for surrender. Put bluntly, they urge people to become reconciled to defeat.

Independent Syrians that I spoke to confirmed that it is very rare for surrendering rebels to be arrested, let alone summarily executed. They also said that in spite of shortages of manpower, the army still observes the long-established Syrian law which exempts boys who are the only son in the family from conscription.

The government’s new strategy of pacification is not popular with all Syrian military commanders. Some have not hidden the fact that they would prefer to defeat, imprison or kill the rebels.

“They hate our guts. They think we’re giving comfort to terrorists,” said Samman. “I remember a colonel telling me: ‘You’re worse than the terrorists. We fight but you give them a chance’.

“But my argument is that it makes sense to allow a couple of hundred fighters to go elsewhere and let a couple of hundred thousand civilians return to normal life.”

Agreements between Syrians

The Damascus region has seen many examples of “reconciliation”. One of the most significant agreements is in the town of Moadimiya, which is situated in a particularly sensitive area, separated from the town of Daraya by the Mezzeh military airfield.

Both towns were subjected to heavy government bombardment. Daraya was particularly hard hit, and many of its people took shelter in Moadimiya, where a truce was agreed with the Syrian army at the end of 2014. Instead of brute force, the government switched to starvation tactics, putting the town under siege.

A bridge over a long-disused railway line formed a no man’s land between the two sides.

Thousands of residents have returned to the ruined town. A newly arrived family disembarked from a pick-up truck laden with mattresses. Water-tankers pulled by tractors were parked in several streets. About a quarter of the shops were open again.

I met Abdelaziz as-Sheikh, a 58-year-old retired colonel, in an office full of men in army combat fatigues. A large portrait photo of Assad was propped up against the wall.

He said he had defected from the army and left for Turkey when rebels from two non-Islamist groups, the Al-Fatah brigade and the Al-Fajr brigade, took Moadimiya over in April 2012.

“I was escaping from both sides,” he told me. “In Turkey I met opposition people who wanted me to join them. They didn’t put me under pressure but I understood it was a conspiracy against my country. There were representatives from Britain and France who I assumed were agents. I refused to be part of the opposition.”

He came back to Syria, and applied to make a taswiya in 2016 when Moadimiya reached a reconciliation agreement and the siege was lifted.

I asked to meet other residents and was taken with my Ministry of Information translator and three young army officers to a well-preserved house several hundred metres behind the old frontline. Despite this formidable military presence, the family did not spare the army and the government from criticism as they described the war.

Sami Halifi, 28, said he stayed in Moadimiya throughout, acting as a photo-journalist for the rebels and putting up pictures on social media of the effects of government bombing and the subsequent two years of siege, he said.

“Because of the bombing we lived in basements from 6pm to 6am,” he said. “People lived on grapes and water. The situation was very bad. About 1,500 civilians were killed. SARC [the Syrian Arab Red Crescent] had a clinic in a basement to treat the injured.”

His mother, Asmaa, nodded as he spoke. “Terrible. It was terrible,” she said.

Sami’s cousin, Mohammed, was one of the Al-Fajr rebel leaders. After two years of siege, he contacted the army about a truce. Months of negotiations followed before a reconciliation deal was agreed. Some 1,200 rebels went to Idlib, of whom 250 have since returned.

People lived on grapes and water. The situation was very bad. About 1,500 civilians were killed

- Sami Halifi

Sami stayed in the town and made his taswiya in 2016. “It didn’t require me to go into the army, because I’m going to college to study economics.”

Similar agreements have been made all over Syria. They are separate from the four “de-escalation zones” which Russia, Iran and Turkey have been setting up with the aim of reaching ceasefire deals.

The advantage of the “reconciliation agreements” is that they are worked out between Syrians with little or no outside input. Although they all mean victory for the government and surrender for the rebels, there is one big advantage for millions of affected Syrians: the war, bombing and siege are over.

What remains is a vast task of reconstruction and a deep legacy of resentment and hatred.

But outright war is no more.

- Jonathan Steele is a veteran foreign correspondent and author of widely acclaimed studies of international relations. He was the Guardian's bureau chief in Washington in the late 1970s, and its Moscow bureau chief during the collapse of communism. He has written books on Iraq, Afghanistan, Russia, South Africa and Germany, including Defeat: Why America and Britain Lost Iraq (I.B.Tauris 2008) and Ghosts of Afghanistan: the Haunted Battleground (Portobello Books 2011).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A handout released by the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) shows Syrians holding portraits of President Bashar al-Assad as they arrive from Jarabulus back to their homes in Homs' Al-Waer neighbourhood on 11 July 2017 (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.