Oslo revisited: Was the US ever the 'honest broker'?

The Oslo Accords marked the first time Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation formally recognised one another.

Not a peace treaty in itself, the Oslo Declaration of Principles signed in the early 1990s aimed to establish interim governance agreements and a framework to facilitate further negotiations for a final agreement that would be concluded within five years.

Crucially, many key issues - including the status of Jerusalem, Israeli settlements in the West Bank and the right of return for Palestinian refugees - were not agreed upon and were set aside for later negotiations.

But nearly 25 years later, there has virtually been no progress.

This move reiterates what everybody already knows: that the US is not an honest broker

- Mazen al-Masri, senior lecturer in law

Trump’s move to recognise Jerusalem - a prominent historic, religious and poltical symbol for the Palestinian cause - as the capital of Israel, has brought the role of the US as an honest peace broker between both parties under sharp criticism.

Many observers say that Trump's announcement proves, more than ever, that the US can no longer be a neutral mediator, rendering the peace process more meaningless than it has already been.

US mediation

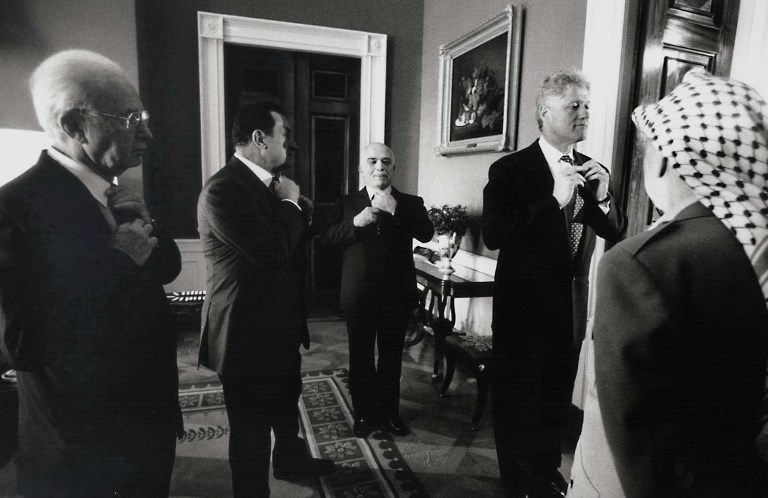

To confirm the agreement signed in the early 1990s, then US president Bill Clinton, Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, along with then foreign minister Shimon Peres, met on the White House lawn.

In the most iconic moment, a smiling Arafat extended his hand to Rabin who, after a brief hesitation, accepted it. The sight of the two longtime adversaries shaking hands was hailed across the world as a major breakthrough in a conflict that at that point had already lasted nearly 50 years.

“The only appropriate response [to Trump’s move] is to annul the Oslo Accords, dissolve the Palestinian Authority and renounce the so-called peace process," Tamim al-Barghouti, Palestinian academic and poet, told Aljazeera on Wednesday. "The Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) should return to its initial aim of liberating the whole of Palestine."

“The so-called peace process was founded upon the assumption that Palestinians would renounce armed resistance and redefine Palestine as merely the West Bank and Gaza Strip… in exchange for the US pressuring Israel into giving back some of the Palestinian lands occupied in 1967.”

Barghouti went on to call on Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas to step down. “Abbas has been telling the Palestinian people that armed resistance will lead to nothing based on the promise that the Americans would give us something. He can't allege this any longer", he said.

The so-called peace process was founded upon the assumption that Palestinians would renounce armed resistance and redefine Palestine as merely the West Bank and Gaza Strip

- Tamim al-Barghouthi, Palestinian academic and poet

“This move reiterates what everybody already knows: that the US is not an honest broker,” Masri told MEE.

“Trump’s statement won’t make any changes on the ground but intensify the the reality of the Israeli apartheid,” he added.

How did the Oslo Accords come about?

The Oslo Accords ended six years of mass protests and armed resistance by the Palestinians known as the First Intifada that began in 1987.

Although the Intifada failed in its goal of ending Israel's occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, images of teenagers throwing stones at tanks won international sympathy for the Palestinian cause and deepened many Israelis' disquiet about the continued occupation.

It also prompted PLO chairman Yasser Arafat to shift his movement's strategy in November 1988, from seeking to reverse the creation of Israel in 1948 with its attendant displacement of the Palestinians, to seeking Palestinian statehood in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Israel did everything, but it was not able to break the will of the Palestinian people (during the Intifada). Oslo broke it.

- Abu Ahmad, West Bank

So following the Madrid Peace Conference in 1991 and eight months of secret negotiations in the Norwegian capital, the accords were signed in Washington in 1993 and Taba, Egypt, in 1995. They were the first peace treaties signed between Israel and the Palestinian leadership.

What did the agreement achieve?

The 1993 agreement led to the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA), an institution intended to serve as a transitional government before the creation of an autonomous Palestinian state. The PA was given limited powers of self-rule, initially in only parts of the Gaza Strip and in the West Bank town of Jericho.

The 1995 agreement divided the West Bank into three zones known as Areas A, B and C.

Area C - some 60 percent of the West Bank - was meant to be "gradually transferred to Palestinian jurisdiction" but remains under full Israeli military and civil control to this day.

While the agreement did not stipulate the creation of a Palestinian state, it implied and foresaw further phased pullbacks by the Israeli army which would eventually lead to one being created.

That two-state vision required Israel to abandon its negation of Palestinian claims to national sovereignty, and Palestinians accept that such claims would be limited to only a small part of the entire territory of historic Palestine for which the PLO had been fighting, recognising Israel’s sovereignty over the remainder.

The hope was that limited Palestinian self-government and incremental Israeli withdrawal would boost mutual trust that would empower leaders on both sides to negotiate final-status agreements on the thorniest issues.

Slow death

There was no single moment when the Oslo Accords can be said to have broken down. Instead, they saw a steady process of attrition as both sides accused one another of failing to implement key aspects of the agreements.

A 1994 massacre by an Israeli settler in Hebron fuelled Palestinian anger, and then, a few months after the second Oslo agreement was signed, a Jewish militant opposed to the agreements shot Prime Minister Rabin at a Tel Aviv peace rally. He died in hospital several hours later along with, many Israelis would argue, the Oslo accords.

Peres took over, but within a year he lost an election to Benjamin Netanyahu - Israel's current prime minister and an outspoken opponent of the agreements.

'For Palestinians, there was no unanimity on the signing of the Oslo Accords. What this statement does, is prove for the one-thousandth time that this approach will not yield any results'

- Mazen al-Masri, City University

Although Netanyahu was ousted in 1999 by Ehud Barak, by then mutual distrust and hostility ran deep, and President Bill Clinton's effort to broker a final-status agreement at Camp David in 2000 ended in failure. The following year, Israel elected another Likud leader, Ariel Sharon, who vowed to end the Oslo Accords.

Sporadic attempts to restart talks over the past decade have produced no further progress towards a final-status agreement. Instead, the Oslo Accords' interim arrangements established a new status quo.

According to Abu Ahmad, a resident of the occupied West Bank refugee camp of Dheisheh who participated in the First Intifada: “Today I believe that no one supports Oslo but those who benefit from Oslo, those who benefit from the continued existence of the PA.

“Israel did everything, but it was not able to break the will of the Palestinian people (during the Intifada). Oslo broke it. The impact of Oslo on the will of Palestinians was twice the impact of the Israelis,” he told MEE.

Masri agrees: “For Palestinians, there was no unanimity on the signing of the Oslo Accords and there have always been people opposed it. What this statement does, is prove for the one-thousandth time that this approach will not yield any results.”

Additional reporting by Chloe Benoist

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.