Diego Maradona in the desert: On the trail of football's lost legend

Diego Maradona is grumpy. He is the last one to step into the floodlights, and he looks around in a gruff manner. The players have already warmed up and begun their evening training little by little, but their manager shows little interest and leaves it all up to his assistants.

Might he be bothered by the dry 40-degree Celsius heat this Arabian evening? Could he be off-colour because of the long drive from Dubai, an hour and a half through the desert and across the Hajar mountains? Does his 57-year-old body hurt when it shuffles towards the football pitch with difficulty and legs so stiff that you almost fear they will collapse underneath him? This is a body that is worn down and marked by far too hard a life.

But no: this is about one of the players who has been getting on Maradona’s nerves.

“We have only been back here for a few days, and already he has started doing tricks and playing with his heel and his toes again. Like this,” says Diego and twitches his feet. “You don’t do that around me. No matter who you are.”

He speaks to his assistant, his former teammate Luis Islas, who was sitting on the bench back in 1986, when Maradona almost singlehandedly took Argentina to victory in the World Cup. Eight years later, Islas was the starting goalkeeper. Maradona’s career in the national team ended dramatically after he failed a doping test at the World Cup in the United States.

Now, Islas listens quietly and patiently to his boss and only when he senses that Maradona has spoken to his heart’s content does he take out a tablet, which he shows his superior while he starts explaining the plans for tonight’s training session. Maradona just shrugs and walks away. He goes around greeting everybody: the other Argentinians from his team get kisses on the cheeks while the local Emiratis get a hug. They all look awestruck.

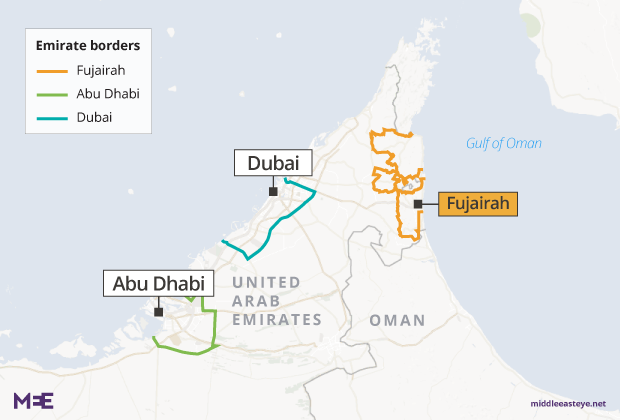

And it is indeed hard to fathom that he is really right here: the legend, Diego Maradona, perhaps the greatest football player ever, here at Fujairah Stadium in the eastern part of the United Arab Emirates, far away from the footballing mainstream, as newly appointed manager for a club in the second division in the country that he has called home since 2011. This is the latest unexpected turn in the remarkable and dramatic story of Diego Armando Maradona.

No one says no to Diego

A few hours earlier, Luis Islas had turned up in the air-conditioned lobby at the City Tower Hotel on the outskirts of Fujairah where the motorway from Dubai meets the seaside town. The former keeper has lived here ever since he came to the Emirates this summer, unlike Diego Maradona, who continues to live in Dubai.

“The heat is incredible; we can either train early in the morning or late in the evening. The local players are used to it, but it sure is special,” Islas said after greeting me.

A few days earlier, Islas, Maradona and the rest of the team returned from a three-week training camp in the Netherlands, and now it is time to refine the last details here in the heat of Arabia before the season starts. Their goal is to be promoted to the first division.

Islas has not worked with Diego Maradona before, but they have known each other for over three decades. “We have often talked about the possibility of working together, but whenever he had a job as manager, I was employed elsewhere. This is the first time we’ve had a chance to make it come true and of course I said yes to Diego. I would never ever say no to Diego. Never.”

As a teammate, he was flawless, and as a person he has very strong views on friendship. Diego is a true friend

- Luis Islas

If loyalty was a criterion when Maradona picked his assistant, then he has certainly picked the right man for the job. Islas has only good things to say about his boss: “Diego is a formidable person. As a player, he was the best – el numero uno. As a teammate, he was flawless, and as a person he has very strong views on friendship. Diego is a true friend.”

Islas did not even know of Fujairah’s existence until his friend Diego was unveiled as the club’s new technical director back in May. The appointment came as a surprise to most people, seeing that a full five years had passed since Maradona’s previous managerial job, at Al-Wasl in Dubai, ended with his dismissal after a chaotic and very disappointing season.

And as the years passed by, with Maradona spending them as sports ambassador for Dubai, most people were beginning to come to terms with the fact that we had probably heard the last chapter in the story of Maradona, the football coach.

That story did not live up to the story of Maradona the football player, but it certainly was not dull. After two short periods working in tandem with his former teammate Carlos Fren at two Argentinian clubs in the 90s, in 2008 he was hired as coach of his home country’s national team at a time of crisis.

During his first year as national coach, Maradona went through 70 different players and suffered a 6-1 defeat to Bolivia, but Argentina scraped through to the World Cup. Maradona dedicated qualification for the World Cup to the Argentinian people but raged against the media, which he believed had treated him badly.

The finals in South Africa in 2010 were a mixed experience for Maradona. Argentina produced some decent performances during the group stage but were humiliated by Germany in the quarter-final. Maradona’s stormy time as national coach came to an end.

“Diego has a passion for football. It is a huge responsibility but he loves it,” said Islas, who was back-up keeper at the World Cup in Mexico in 1986 at the age of 20.

Eight years later, the keeper played in all four matches as Argentina were knocked out of the finals in the US during the round of 16 after Maradona had tested positive.

“I don’t reckon there will ever be anyone like Diego,” he said. “He was number one because of everything he gave on the field. He won the matches for us, for instance during the quarter-final against England in 1986 which was a tough and level game, and then all of a sudden Diego did something magical. There are also good players today, but Diego is different - he is in a league of his own.”

I took my leave of Islas and told him I would be back for the training in the evening. I asked if I might have a chance to talk to Maradona afterwards. “Let’s see. You never know with Diego.”

The time when Diego almost died

Unpredictability and drama have characterised Diego Maradona’s entire life. He inherited a heart condition from his father, yet started taking cocaine in the early 80s. In the years following his active career, it has placed his life in danger. In 2000, he collapsed during a holiday in Punta del Este in Uruguay and the local police report documented extensive use of cocaine.

Maradona went through rehab in Cuba as a guest of Fidel Castro. Castro and Che Guevara were always among Maradona’s personal heroes; an important part of his identity is his poor background and opposition to the elite.

“I am the voice of those who have no voice,” he declares in El Diego: The Autobiography of the World’s Greatest Footballer, which sold 125,000 copies in the first week after it was published in Spanish in Argentina in 2000.

I almost died at one point. Only my daughters’ love saved me

- Diego Maradona

It is, however, hard to discern any clear-cut ideology: an array of politicians with varying beliefs have connected Maradona to their cause. He was a natural part of Latin America’s nationalist current in the first decade of the 21st century, and in 2005 he stood side by side by Venezuela’s then-president Hugo Chavez during an anti-US protest in Mar del Plata.

At the time, Maradona was in the midst of one of his many comebacks. In 2004, he had been hospitalised again and had a stomach operation the year after. Subsequently, his health improved so much that he was able to host his own talk-show on Argentinian TV: La Noche del 10 – ‘The Night of the 10’.

On this show, Maradona admitted for the first time ever what everybody knew: that he did indeed use his hand when he scored against England during the World Cup quarter-final in 1986. An impressive battery of celebrities showed up on La Noche del Diez, but the host was the undisputed protagonist, even if the guest was Pele or Fidel Castro. El Diego sang, danced, joked, juggled and talked about himself and his life and hugged his guests.

“I almost died at one point,” he told Pele when the Brazilian was his guest on the programme. “Only my daughters’ love saved me.”

A particularly memorable episode of the programme featured Maradona interviewing himself about his drug abuse. One Diego asked the other when he had last done drugs. The answer was that it had been a year and a half. But he was still a troubled man who mostly stayed at home and passed the time by watching as much football on television as possible.

And Maradona got himself into trouble again: in 2007, he was hospitalised once more and had to go to rehab for alcohol abuse. And in 2015, after moving to Dubai, he had to undergo yet another stomach operation.

The sheikh’s big dreams

Against this background, it is welcome news that he is still among us to stand here in the stadium in Fujairah. He gathered his players on the field and talked to them in Spanish.

“We must continue with the same attitude and going on doing a good job,” Maradona said, and his words were translated into Arabic by his interpreter Mohammed el Naggar.

Islas divided the players into two teams. They started playing on the large field in both goal areas. Two players on each team were stationed in the penalty area at all times, and no other player was allowed to enter it. Maradona came to life as the game got going. He strolled around the middle of the field, holding a ball, with a whistle hanging around his neck.

“That’s it. Come on. Pass it. Well done.”

Diego pointed and yelled, and next to him the interpreter Mohammed did the same, not only imitating Diego’s words, but also copying his body language in an almost comical manner. The players’ level is none too high, but by then Maradona had become so lively that his deep voice drowned out the prayer calls from the minarets of Fujairah.

“It’s like a dream,” he said. “I lack words to describe what it is like suddenly to stand in front of him and talk to him and get hugged by him. He is a formidable person. He is not just our manager; he is our friend.

“When we were in the Netherlands, people from the whole world came and he took his time with everybody every day. He posed for photos with everyone. Have a look here.” Abdullah showed me an enormous folder on his computer with photos of Maradona posing with children and grown-ups. He is smiling in most of the pictures.

I lack words to describe what it is like suddenly to stand in front of him and talk to him and get hugged by him

- Abdullah, Fujairah FC's press officer

Abdullah has great expectations for the potential Maradona’s presence could have for this club and the town. Fujairah is the capital of the emirate of the same name, one of seven that make up the United Arab Emirates.

The place has grown a lot since the middle of the 90s; the number of inhabitants has more than doubled to 215,000. It is still a town, however, that is overshadowed by Dubai and Abu Dhabi, and the Fujairah emirate has traditionally been one of the less developed parts of the country.

They are trying to change that now. New shopping malls have sprung up, although not to an extent that would compare with those in Dubai, beyond the mountains. On the other hand, the location of Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman is strategically important and this means that the Fujairah Oil Terminal is growing ever bigger and is used as a staging post by foreign companies.

Pipelines carry oil across the country from Abu Dhabi to Fujairah to avoid the cumbersome sea journey through the Strait of Hormuz between the Emirates and Iran.

The town’s new mosque is the second biggest in the country, but there is still a long way to go before Fujairah achieves real fame. This is the idea behind hiring Maradona as manager of the club that was relegated from the first division in 2015.

How much Maradona is paid for his efforts is unknown, but it has not gone without comment that the man who has spent his life acting as the man of the people and backing Fidel Castro and Che Guevara is now earning oil money in the Middle East.

When in August Maradona went so far as to express his support for Nicolas Maduro – Venezuela’s controversial president during the current crisis – and declared himself “chavista hasta la muerte”, a lifelong supporter of Maduro’s predecessor and idol Hugo Chavez, it became too much for some.

Among them was Jose Luis Chilavert, Paraguay’s former national team goalkeeper. “Maradona is burnt out, and it is just typical that he supports the murderers of the Venezuelan people. He speaks up against imperialism while living in Dubai himself,” tweeted Chilavert.

Fidel Castro is dead and Latin American nationalism is tired, having been sapped of much of the strength it could boast a decade ago, when Maradona stood side by side with Hugo Chavez, paying tribute to the so-called Bolivarian revolution and to 21st-century socialism.

The question is where that leaves Maradona: does he still have a role to play or has he become a parody of his former self? Is he now someone who is no longer relevant either to football or to politics and merely lives through his past and the reverence with which he is still treated?

God’s hand in Fujairah

So far here in Fujairah, there is no sign that the world-famous Diego is in town. There is no sign of him in the very warm streets: in the souk, dates, spices, fruits and meat are for sale; the fishmongers sit in a circle, cleaning and filleting their catch on chopping blocks shaped like tree stumps, while tailors sell the traditional kandura robes; but no one is selling Fujairah football shirts.

Likewise, in the street in front of the stadium where the entrance is squeezed in between an electronics store, a tile shop, an estate agent and a bakery, all is quiet before the legend’s arrival for evening training. And this is the case even though people are welcome to come in and watch, according to Abdullah.

“We are having new player shirts made and soon merchandise will arrive from China. We will be opening a fan shop here in Fujairah; we have not had one before. We will also open one in Dubai. And we will refurbish the stadium when we get promoted to the first division.”

Not if. When.

I ask Abdullah if it does not pose a problem that Maradona still lives in his house in Dubai and has failed to move to Fujairah.

“We are building him a house; it will be ready in a few days, and then he will move here,” Abdullah said.

When I asked Abdullah if I could talk to Maradona after training, he hesitated. He did not look like someone who would be very happy to ask him.

Down on the pitch, training was just about over. Maradona gathered the players together and was in a much better mood than he was upon arrival. He clapped his hands.

“Very nice work today,” he said, and his interpreter translated.

Some of the players started practising swinging crosses into the box and Diego played along and placed himself in the penalty area. The players were clearly trying to hit their manager, and sometimes they managed to. “Ultima,” yelled Diego. Last ball, but it was way off, so they tried one more.

This time, the cross was better but still a touch too high for the player in the area, who jumped up and hit the ball into the goal with his hand. Diego blissfully clapped.

The players went off to change and Maradona strolled around, handing out hugs and laughing. With help from his interpreter, he told a story to one of the locals, who did not seem to understand him but laughed along anyway. It was something to do with some money from the Netherlands that has arrived now.

Islas walked over to Diego, talked to him a bit and pointed me out. Diego nodded and a moment later Abdullah came over.

“Count yourself lucky; you are the first journalist he has agreed to talk to since his arrival,” he said.

But first, Diego sat down on a plastic crate, and Islas and the other Argentinians from his staff gathered together and sat on the grass before him.

Diego did most of the talking, while the others listened and laughed whenever it was expected. It dragged on. Diego had many stories to tell. I imagined that this is what it looked like back in 1986 when El Diego carried the Argentinian national team to the World Cup in Mexico.

Invitation to a lap of honour

Finally, he got up, and instantly everybody else did the same as if all they were waiting for was permission to be dismissed. No one left before the boss. Maradona came over and said hello to me, standing in a formal manner with his hands behind his back. I asked him what he has found in the Emirates and how the years spent here have affected him as a person.

“I haven't changed as a person,” he said. “But here, I have met good people who have treated me very well. I have enjoyed these years with my family and worked for the emirate and as a sports ambassador. I am happy. Now I have been given the chance to work with Fujairah FC and I take it very seriously.”

I tried in vain to catch his gaze, but he avoided eye contact, looking to the side or down on the ground. His eyes are big and brown, the furrows on his forehead deep. “This has shown me that there are still good people in this world,” he said, “people with whom you can work in an honest manner without corruption and without robbing anyone.”

He went on to talk about the villains of the recent past, making allegations that remain unproven.

“They have left us with a very big hole to fill. People in FIFA used to believe that the money from football was for them personally and not for football. Coca-Cola would write a cheque to [former FIFA Sepp] Blatter, and Blatter would cash it in and put the money into his own bank account. [Former Argentine football president Julio] Grondona did the same, as did [former Spanish football president Angel Maria] Villar; they all did. They stole money from football. These types should not even be allowed into a football game, because they stole from football, they robbed the people who paid for their tickets. This is why Infantino has huge problems today: he needs to tidy up their mess. It’s a catastrophe.”

Blatter resigned as FIFA president in 2015 with corruption allegations swirling around world football's governing body and was subsequently banned from football by FIFA's ethics committee for six years. But he has denied all corruption allegations.

I’ll invite you to come see the lap of honour when we get promoted to the first division

- Diego Maradona

Grondona, who died in 2014, asked for payments in return for voting for Qatar to host the 2022 World Cup, according to the testimonies heard during the trial in New York this month of three former South American football officials.

Villar was arrested in Spain earlier this year and faces trial on corruption charges which he denies.

Maradona had perked up and was almost agitated. As he went on, he poked me in the chest. “It might happen again; it has not been solved,” he said.” If I say, ‘So, you have robbed me, all right, you go to prison’ — but you have already passed the money you stole from me on to your son or your sister or your wife, to whomever, that money needs to be returned. The money must be returned. But I am very happy here.”

He laughed, abruptly. “I’ll invite you to come see the lap of honour when we get promoted to the first division.”

We only spoke for a few minutes, and during that period he changed mood several times, from listless to agitated to buoyant; El Diego has many faces.

We started walking towards the players’ tunnel. The drive to Dubai awaited. I had to ask him about the last goal during that evening’s training, the hand-made one.

“It rather looked like a tribute to you, didn’t it?”

“To me? Ha ha!”

“Was the goal valid?”

“No, no. It wasn’t valid as now there are video referees, right. Me, however, they did not see,” Maradona said with a smile, as he bade me farewell and took his girlfriend’s hand.

The 56-year-old Maradona and the 27-year-old Rocío Oliva walked down the hall hand in hand. Another day of work was over for Fujairah’s new manager.

Translated from Danish into English by Sara Hoyrup.

This story was originally published in Issue 27 of The Blizzard magazine in December 2017.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.