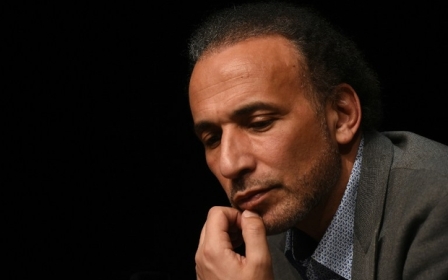

Is Tariq Ramadan going to get a fair trial in France?

Since 2 February, Tariq Ramadan, one of Europe's most influential Muslim intellectuals, has been in preventive detention and solitary confinement at Fleury-Mérogis prison in France, following rape charges by two women, which he fully denies.

The issues raised here have nothing to do with Ramadan's alleged guilt or presumed innocence. These are serious charges and Ramadan should face them in court. Those who claim otherwise, on either side of this supercharged case, can only do so out of bad faith, prejudice or disingenuousness.

That being said, the French justice system's handling of the pre-trial conditions in the case has been dogged by controversy, allegations of denial of justice, and violation of due process.

The degree to which the system has deviated from normal practice has shocked even Ramadan's critics such as the French attorney Régis de Castelnau who described the denial of due process as "severe and constant".

Legal problems

The first issue was the refusal to grant bail and the decision to detain Ramadan in custody. Ramadan's bail request was never considered. Incarceration is usually a measure of last resort when other options such as house arrest, electronic bracelet, or reporting to a police station are not available or realistic.

The judges argued that if free, Ramadan would pressure his accusers into dropping their claims. This is absurd. It would take a world-class imbecile to attempt to do this in this case, knowing how such a course of action could be used against him.

The second argument used was flight risk. Ramadan is a Swiss citizen. There is no evidence that Ramadan would flee to a country with whom the EU has no extradition treaty. Ramadan has co-operated fully with the French system and surrendered himself voluntarily to the court.

Among the dozens of similar cases of rape, many with formal charges, that have emerged in France (and elsewhere) in the wake of the #MeToo movement, Ramadan is the only one who has been jailed like this

Ramadan has not just been kept in custody. He has been kept in solitary confinement. His wife and children have been denied rights to visit him. This constituted another measure for which the judges have provided no explanation.

When the first complaint against Ramadan was filed, it was at the Public Prosecutor's office in Rouen. Logically, Rouen should have received natural jurisdiction over the case; however, the Rouen jurisdiction was waived in order for it to be moved to the Paris prosecutor's office.

This allowed the Ramadan case to be transferred to Prosecutor François Molins, who specialises in cases of Islamist terrorism which occur within the French national jurisdiction.

Molins has become a familiar figure in France. For three years he has been a face on television, often in lengthy and dramatic interventions, giving us updates on each of the terrorist cases that have shaken French public life - the Charlie Hebdo case, the Nice attack, and other less lethal attacks as they were unfolding.

For the French, Molins has become the main face of counter-terrorism. Mr Islamist Terrorism in person, or the "Prosecutor of French Jihadists" as some fondly call him. Anyone wishing to associate Ramadan with Islamist terrorism could not have found a better man.

Lost alibi

The most egregious example of mistreatment has yet to come: on 6 December Ramadan's lawyers formally filed a document with the Paris prosecutor's office. This was hard evidence to back an alibi Ramadan had against one of the two charges.

It contained travel documents including a London-Lyon plane ticket which purported to show that at or around the time the second accuser (the anonymous "Christelle") alleged he was raping her in his Lyon hotel room shortly before a conference, Ramadan was not in the country.

This is despite the fact that the Paris prosecutor's office did formally confirm to them on 6 December (the same day the lawyers filed it) that it had indeed been sent to the proper authorities for inclusion in the investigation (they therefore could not know it had not been the case).

When the lawyers realised it was missing and asked where it was and what had happened these past two months, the document resurfaced immediately on 1 February. Again, no explanation has been given for this other than "we don’t know".

But the damage had already been done: it was then too late for formal judicial consideration of that item and verification of Ramadan's alibi. The next day, on 2 February, Ramadan was incarcerated.

Due to his failing medical condition in prison, Ramadan has for three weeks now been rendered unable to adequately work on his own defence, which already amounts to a denial of justice

To this day, no explanation for that prolonged "loss" has been offered by the Paris prosecutor's office. Even more shocking, the travel document has still not been verified by the police and court authorities.

Had this happened in a US court, the loss and discovery of such a document would probably have led to the immediate liberation of the accused on the ground of violation of due process and denial of basic rights. But not in France where no one cares.

The judges in charge of the case had repeatedly declared they were so aware of how sensitive this affair was they put three judges on the case, instead of one, and they would handle it with utmost care. Utmost care? Needless to say, his alibi was the one and only legal item "lost" by the justice system. But that must be pure coincidence. Accidents happen.

Failing health

On 17 February, according to an Agence France Presse report, a first medical examination conducted in prison (by the prison doctor) had assessed that Ramadan's health condition was "incompatible with detention".

This diagnosis was corroborated by two other doctors - Ramadan's private doctors in London and in France. Despite this, the judge to whom the three medical documents were given decided to prolong Ramadan's detention as well as his solitary confinement.

On Monday, another medical report was issued contradicting the initial medical report and suggesting Ramadan had no health issues. However Ramadan has since been hospitalised.

Due to his failing medical condition in prison, Ramadan has for three weeks now been rendered unable to adequately work on his own defence, which already amounts to a denial of justice.

Travesty of justice

As more and more people start to realise with each disturbing new revelation (and we have to be selective here as there is more, all of the same type, coming out daily now), the justice d'exception specifically applied to Ramadan can simply no longer be denied.

The travesty of justice has been so unusual that even some of Ramadan's adversaries are worried this may durably affect the integrity of the institution of justice and the confidence people can place in it.

For that conclusion we need to rely on no more than the judgment of the attorney de Castelnau, who has disparagingly called Ramadan "a preacher" and a "guru”, and has been Ramadan's ideological and political opponent.

The lawyer's concern is that the extreme denial of due process in this case will actually backfire against those who, like him, want and need to use the courts to fight "radical Islamism". His legal analysis of the Ramadan case is sobering too, concluding upon close examination of all the documentation and data available so far that the denial of due process has been “severe and constant”.

De Castelnau published his conclusion on 9 February, before the more recent developments such as the news of Ramadan's deteriorating health conditions, the medical documentation showing he cannot sustain incarceration, and more.

The travesty of justice has been so unusual that even some of Ramadan's adversaries are worried this may durably affect the integrity of the institution and the confidence people can place in it

De Castelnau found that the entire investigation leading to Ramadan's preventive detention on 2 February was conducted entirely and exclusively à charge (meaning exclusively against the defendant), and "severely so".

Especially, he adds, "during the interrogations and confrontations [with one of the two women] that took place before the decision to jail him". He noted with surprise that none of the inconsistencies and contradictions in the testimonies of the plaintiffs was examined by the judges.

Ramadan's lawyers, who at that time did not have access to those court files, were thus not able to use them for his defence.

Double standards

The exceptionalism with which Ramadan has been treated, itself a violation of France's constitutional obligation to guarantee equality before the law, is even clearer when we compare it to similar charges against other high-profile figures and how those cases have been handled.

Among the dozens of similar cases of rape, many with formal charges, that have emerged in France (and elsewhere) in the wake of the #MeToo movement, Ramadan is the only one who has been jailed like this.

But the blatant examples of France's differential treatment has been the issue of two leading ministers in Emmanuel Macron's cabinet who have been accused of rape (each by two women, like Ramadan).

They are the Budget Minister Gerald Darmanin, "the new Sarkozy", and Minister of the Environment Nicolas Hulot, a former ecological activist, journalist and immensely popular television figure, in France a true cultural icon since the 1980s.

Besides some embarrassing media attention, for which they whined at length in deeply empathic and compassionate interviews during which they could also defend themselves, unlike Ramadan, they have had to endure no more than a brief police interrogation as is obligatory in such cases.

As soon as the rape charges became public and the normal legal procedure started, the whole of Macron's government, including the prime minister, Edouard Philippe, and the president himself rallied around Darmanin, then Hulot.

One of those accusers was at the time of the alleged crime a minor, though Hulot denies the charges. He has also been accused by late French president Francois Mitterrand's grand-daughter, Pascale Mitterrand.

The key moment of this touching and determined unanimous show of support was when Darmanin entered the French National Assembly the day after the first preliminary investigation against him was opened.

Before investigation results came out, the MPs of the Macron majority gave him a standing ovation. Darmanin actually admitted he had had sex with the "call-girl" who is now accusing him of rape, in exchange for a favour to her in a legal case.

Fair trial?

As we see, in France, everything is relative, flexible and adjustable depending on whom is being accused. The same double standard can be observed in the media treatment of Ramadan vs Darmanin and Hulot.

While the best Ramadan got was feeble and occasional lip service to the presumption of innocence, since the Darmanin affair emerged, the media have all suddenly switched to a different mode, a much more "embarrassed" one, and to a new theme, that of "media ethics" that need to be reaffirmed to avoid the "excess" of the "out-of-control" coverage of the Hulot case.

The mainstream media in France are touchingly self-critical about the "lynching" of Hulot, describing the coverage as "dérapage" (a bad mistake), and forcefully, this time, reasserting Hulot's presumption of innocence.

They are even now campaigning against the "tyranny of transparency", while sensationalist magazine covers and headlines are asking, everywhere, in apparent opposition to the #MeToo movement that yesterday they were celebrating: "Should we expose everything" in our "media tribunals"?

So noble. Oddly enough, Ramadan has never been evoked in those debates and remains absent from the crisis of conscience of the French media.

And the same national news media which yesterday was featuring the Ramadan accusers in the most empathic, compassionate (and of course uncritical) manner, are now using character assassination against the women who pressed charges against the two ministers.

None of this pertains to the facts of the Ramadan case. He is either guilty or innocent. But all of this certainly suggests he is unlikely to receive a fair trial, such has been the abuse of power in this case.

- Dr Alain Gabon is an associate professor of French studies based in the United States and the head of the French Department at Wesleyan University. He has written numerous papers and articles on contemporary France and on Islam in Europe and throughout the world for academic journals and think tanks, including Britain's Cordoba Foundation and mainstream media outlets, such as Saphirnews and Les cahiers de l'Islam. His essay entitled ‘Radicalisation islamiste et menace djihadiste en Occident: le double mythe’ appeared in a September 2016 Cordoba Foundation publication.

Opinions expressed in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Tariq Ramadan during a conference in Paris on 7 April 2012 (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.