Turkey's 'Mathematics Village': Changing education, one equation at a time

SIRINCE, Turkey – Morning sun rays filter through stained glass windows, shining on a group of teenagers and students in their 20s, sitting on wooden benches having breakfast.

Situated near the small Agean village of Sirince, about 10km from the ruins of the ancient Greek city of Ephesus, it could resemble any other summer camp if it weren't for the students mulling over intricate polygons and matrices.

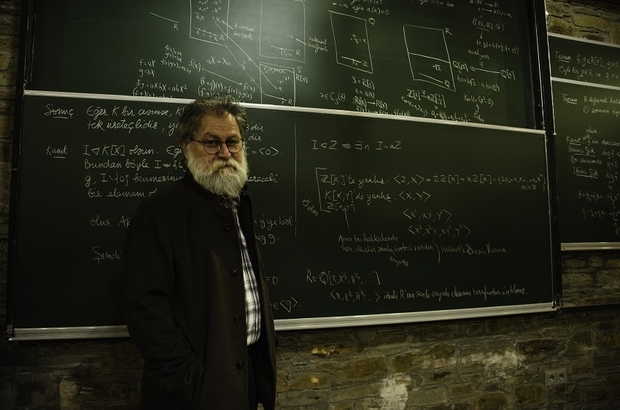

Created in 2007 by Ali Nesin, a visionary mathematician in his sixties with a PhD in mathematical logic from Yale University, Sirince’s "Nesin Mathematics Village" is dedicated to studying maths. Standing on a hillside amid an olive grove, it comprises about 30 buildings, mostly built from rock, straw and clay, over a surface of 13.5 acres.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“This is our kindergarten," says Alp Bassa, a volunteer lecturer at the village and a maths professor at Istanbul's Bogazici University. "The only place in Turkey where we can focus on our passion."

Every year, more than 10,000 students from primary school-level to university attend the village's maths programmes. Courses last from a few days to several weeks and are organised all year round, although most classes are held in the summer and during school holidays.

Nesin says it cannot host everyone who applies. "We refuse many people. We can only host up to 500 students at once."

The logic of the village

For Serkan Dogan, a 22-year-old student at Bilkent University in Ankara, coming to the village was life-changing. He visited for the first time when he was 15 after learning about it in a mathematics journal. After he turned 17, he came back every winter during his holidays for week-long programmes.

'Maths was all about memorisation. When I asked why formulas would lead to such or such result, I was told to remember the result without explanation. Here, I learnt how to solve the problems. And this reasoning can be used in everyday life'

- Serkan Dogan, student

Dogan explains that he was frustrated by how maths was taught in high school. “It was all about memorisation. When I asked why formulas would lead to such or such result, I was told to remember the result without explanation,” he says. “Here, I learnt how to solve the problems. And this way of reasoning can be used in everyday life,” he adds.

For Begum Cakti and Buket Eren, students in their early 20s at Koc and Galatasaray Universities respectively in Istanbul, attendance at the village is a necessary step to becoming a researcher. “Here we have direct access to highly competent professors and we are studying with better students from other universities,” says Eren.

When he first created the village, Nesin targeted only university students. After he found that the students’ level was too weak and they needed to learn more basic concepts, he shifted his focus to high school students and later primary school students.

This is our kindergarten. The only place in Turkey where we can focus on our passion

- Alp Bassa, maths professor, Bogazici University

Atakan Sen, 17, a student at Galatasaray High School in Istanbul, says he came to the village because of his strong interest in maths.

“The rational thinking of mathematics can be applicable to many aspects of our lives. It is a waste to learn them without understanding them,” Sen explains.

Prime numbers

Lecturers, who all work on a volunteer basis, are invited to teach what they enjoy and what they would not be able to teach in a university or school setting. Ozer Ozturk, professor at Istanbul's Mimar Sinan University, says he continues to be amazed at the students’ motivation.

“Usually, when the bell rings the children just run away. Here, they ask the teachers to finish the [lecture] even if it means going over the lunch break,” he says.

Some professors explore new approaches to teaching maths. “We want to change the approach to the subject in order to intrigue the students and make them understand properly,” explains Ozturk. For him, this should start at the earliest age possible.

Usually, when the bell rings the children just run away. Here, they ask the teachers to finish the [lecture] even if it means going over the lunch break

- Ozer Ozturk, professor at Istanbul's Mimar Sinan University

Over dinner, he experiments with a method to teach division using a "goose game" with his colleague Hakan Gunturkun from Galatasaray University. The game involves geese made out of napkins and a board divided into numbered squares and dice.

Gunturkun says: “Children should start learning mathematics at an early age by playing games. It is intuitive and much more fun for them than sitting in front of a blackboard with abstract concepts and figures."

When asked whether their methodology could become common in Turkey, Gunturkun and Ozturk smirk.

“The education system in Turkey, like everywhere in the world, is very conservative. It doesn’t aim at developing the personality of the children, let alone their intelligence,” Ozturk says.

Like Nesin, who is still chair of the mathematics department at Bilgi University, the professors advocate a radical transformation of Turkey’s schooling system.

According to a survey of academic performance published in 2016 by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Turkey slipped an average of eight places in the survey’s rankings for science, mathematics and reading to 50th among 72 countries, compared with the previous study three years earlier. This was despite a substantial budget increase from the ministry of education.

The education system in Turkey, like everywhere in the world, is very conservative. It doesn’t aim at developing the personality of the children, let alone their intelligence

- Professor Ozer Ozturk, Istanbul's Mimar Sinan University

Nesin says: “Education is too centralised. There are 25 million students in Turkey. All study the same programmes with the same exercises, but their needs, languages, capacities are different. Plus the training of the teachers should be dramatically improved."

Building blocks for the future?

The first stone of the Nesin Mathematics Village was laid during the summer of 2007 when 90 university students pitched their tents on an olive grove atop a hill one kilometre from Sirince. The piece of land was owned by the Nesin Foundation and the construction was financed through donations made specifically for the village through the foundation.

In the mornings, university students would study maths and in the afternoons they would take part in the construction of the village as part of the camp’s activities.

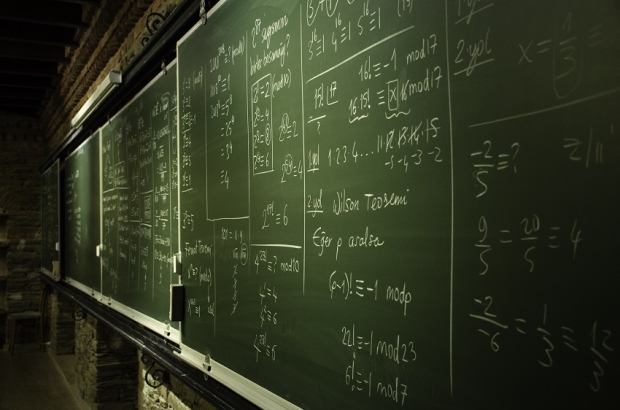

“At the beginning, the village was just a building with chairs and two blackboards. The only things needed to make a mathematician happy,” remembers Durhan.

The construction work was done under the supervision of Sevan Nisanyan, a Turkish intellectual of Armenian descent, who is a self-taught architect and expert in renovating historical buildings.

Nisanyan is known for renovating his home village in Sirince and turning it into a tourist attraction. Although the first building was constructed by students, the rest were built by professionals hired by Nisanyan and Nesin.

Nisanyan now lives in exile in the Greek island of Samos after escaping from prison in July 2017, where he was serving an eight-and-a-half-year sentence on charges of breaking zoning laws in Sirince.

There have been other problems. In 2007, Nesin had a run-in with authorities over construction permits. He said that he had, in fact, applied for the permits but was denied them because of his background.

Maths and responsibilities go hand in hand. Both make students more independent. There are children here who have never done any domestic chores at home

- Ali Nesin

The son of a controversial figure, Nesin’s name is associated with his father Aziz Nesin, an outspoken satirical writer, atheist and critic of Islamic fundamentalists.

Eventually, the police gave up on evicting Nesin and his students and the construction continued. But he was sued that same year by the state for illegal construction and illegally creating an educational institution. He was acquitted in the first case, but the second case is still ongoing with little progress.

Nesin counters: “It is too late for that. Our village is too popular now."

In a little over 10 years, the Nesin Mathematics Village has grown to include more than 30 buildings, including two canteens, dormitories, comfortable bedrooms and classrooms - and even a hamam (Turkish bath).

The village was built and is run thanks to private donors whose names are listed on the wall of one of the buildings, supported by a small fee paid by students and visitors. The cost is about $20 a day, which includes food and accommodation for the whole programme. For students who cannot afford the cost of the stay, the Nesin Foundation provides grants.

Education is too centralised. There are 25 million students in Turkey. All study the same programmes with the same exercises; but their needs, languages, capacities are different

- Ali Nesin

The village is built around an old-fashioned library where the largest lectures are held. It now has open-air amphitheatres – the largest of which can seat about 200 people – and even an ornamental watchtower.

As well as learning, the students have their share of daily tasks. Each student helps out with washing dishes, tidying up rooms and common areas, cooking, serving food, and helping with the general upkeep of the village.

“Maths and responsibilities go hand in hand. Both make students more independent. There are children here who have never done any domestic chores at home,” explains Nesin.

‘An elite curriculum’

In the 1980s, after receiving his Master's degree from Paris Diderot University, Nesin got a PhD in Mathematical Logic from Yale University and later became a professor at Irvine University in the US.

When his father, Aziz, died in 1995, Nesin returned to Turkey to take over the management of his father’s “Nesin foundation,” a boarding school dedicated to the education of young orphans.

He was then asked to create a department of mathematics at Istanbul Bilgi University, which was set to open in 1996.

The future of the country lies in our hands. In ten to 30 years, these students will be the leaders, directors, scientists, professors, artists, lawyers and intellectuals of Turkey

- Ali Nesin

“I accepted. It’s the dream of any mathematician to build a maths department. So I looked at what was missing in Turkey, which was an elite teaching of mathematics."

Nesin says he created a curriculum at the level of the world’s best universities. “At that time I believed that by training 10 elite mathematicians a year for 30 years, I would change Turkey and the world.” But his students did not meet his standard of education and struggled to make it to the next year.

Salih Durhan, one of Nesin’s first pupils and a teacher at the village, recalls: “In 1997, out of 30 classmates, only four of us moved on to the second year at Bilgi University. The rest had failed.

“Nesin was teaching us subjects in a way that was completely new to us. In high school, we were just learning things by heart. We had never been taught to understand them."

To help his students at Istanbul Bilgi University, Nesin arranged evening and weekend courses, which eventually shifted in 1998 to summer camps in Antalya, on the Mediterranean coast.

“Nesin used to say that mathematicians could not take a three-month holiday. It was kind of an obligation to come to the camps,” explains Haydar Goral, who was a student of Nesin’s in the early 2000s and is now a maths professor at Koc University in Istanbul. Goral has been a lecturer at the village since 2010.

In 2004, Nesin opened the summer camp to students and professors from universities other than Bilgi. “It is when I realised that Turkey needed a permanent place to study mathematics and that I should start working on creating the mathematics village,” he says.

The mathematician has recently opened his village to activities related to philosophy and social sciences, as well as art. A long-term goal of Nesin's is to open a high school where he intends to implement his methods on a larger scale.

“The future of the country lies in our hands. In 10 to 30 years, these students will be the leaders, directors, scientists, professors, artists, lawyers and intellectuals of Turkey,” he says.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.