The crimes of 1948: Jewish fighters speak out

For the Israelis, 1948 represents the high point of the Zionist project, a major chapter in the Israeli national narrative when the Jews became masters of their own fate and, above all, succeeded in realising the utopia formulated 50 years earlier by Theodor Herzl – the construction, in Palestine, of a state of refuge for the "Jewish people".

For the Palestinians, 1948 symbolises the advent of the colonial process that dispossessed them of their land and their right to sovereignty – known as the “Nakba” (catastrophe, in Arabic).

In theory, Israeli and Palestinian populations disagree over the events of 1948 that drove 805,000 Arabs into forced exile. However, in practice, Jewish fighters testified early on to the crimes of which they perhaps played accomplice, or even perpetrator.

Dissonant voices

Through various channels, a number of Israelis would testify to the events of the day, as early as 1948. At the time of the conflict, a number of Zionist leaders questioned the movement's authorities on the treatment of Arab populations in Palestine, which they considered unworthy of the values the Jewish fighters claimed to defend. Others took notes hoping to testify once the violence had stopped.

Yosef Nahmani, a senior officer of the Haganah, the armed force of the Jewish Agency that would become the Army of Defence for Israel, wrote in his diary on 6 November 1948: “In Safsaf, after the inhabitants had hoisted the white flag, [the soldiers] gathered the men and women into separate groups, bound the hands of 50 or 60 villagers, shot them, then buried them all in the same pit. They also raped several women from the village. Where did they learn such behaviour, as cruel as that of the Nazis? [...] One officer told me that the most ferocious were those who had escaped the camps."

During the conflict, a number of Zionist leaders questioned the movement’s authorities on the treatment of Arab populations in Palestine, which they considered unworthy of the values the Jewish fighters claimed to defend

The truth is, once the war was over, the narrative of the victors alone was heard, with Israeli civil society facing a number of far more urgent challenges than that of the plight of the Palestinian refugees. People who wanted to recount the events of the day had to turn to fiction and literature.

In 1949, the Israeli writer and politician, Yizhar Smilansky, published the novella Khirbet Khizeh, in which he described the expulsion of an eponymous Arab village. But according to the author, there was no need to feel remorse about that particular chapter of history. The “dirty work” was as a necessary part of building the Jewish state. His testimony reflects, instead, a kind of atonement for past sins. By acknowledging wrongs and unveiling them, one is able to cast off the burden of guilt.

The novel became a bestseller and was made into a TV film in 1977. Its release provoked heated debate since it called into question the Israeli narrative claiming the Palestinian populations had left their lands voluntarily to avoid living alongside Jews.

The Deir Yassin massacre

On 4 April 1972, Colonel Meir Pilavski, a former Palmach fighter, was interviewed by Yediot Aharonot, one of Israel’s three largest daily papers, on the Deir Yassin massacre of 9 April 1948, in which nearly 120 civilians lost their lives. His troops, he claims, were in the vicinity at the time of the attacks, but were advised to withdraw when it became clear the operations were being led by the extremist paramilitary forces, Irgun and Stern, which had broken away from the Haganah.

From then on, the debate would focus on the events at Deir Yassin, to the point of forgetting the nearly 70 other massacres of Arab civilians that took place. The stakes were high for the Zionist left: responsibility for the massacres would be placed on groups of ultras.

The debate would focus on the events of Deir Yassin, to the point of forgetting the nearly 70 other massacres of Arab civilians that took place

In 1987, when the first works of a group of historians known as the Israeli "new historians" appeared, including those of Ilan Pappé, a considerable part of the Jewish battalions of 1948 were called into question. For those who had remained silent in recent decades, the time had come to speak out.

Part of Israeli society seemed ready to listen as well. Within the context of the First Palestinian Intifada and the pre-Oslo negotiations, pacifist circles were ready to question Israeli society on its national narrative and its relationship to non-Jewish communities.

These attempts at dialogue ended suddenly with the outbreak of the Second Intifada, which was more militarised and took place in the aftermath of the failed Camp David talks and the breakdown of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. The Katz controversy would perfectly embody the new dynamic.

The Katz controversy

In 1985, a 60-year-old kibbutznik, Teddy Katz, decided to resume his studies and enrolled in a historical research programme under the direction of Ilan Pappé at the University of Haifa. He wanted to shed light on the events that took place in five Palestinian villages, deserted in 1948.

He conducted 135 interviews with Jewish fighters, 64 of which focused on the atrocity that allegedly took place in the village of Tantura, cleared of 1,200 inhabitants on 23 May 1948 by Palmach forces.

After two years of research, Katz states in his work that between 85 and 110 men were ruthlessly shot dead on Tantura beach, after digging their own graves. The massacre would then continue in the village, one house at a time, and a man hunt was played out in the streets. The killing only stopped when Jewish inhabitants from the neighbouring village of Zikhron Yaakov intervened. More than 230 people were murdered.

In January 2000, a journalist from daily Maariv newspaper decided to talk to some of the witnesses mentioned by Katz. The main witness, Bentzion Fridan, a commander for the Palmach forces present in Tantura, denied the whole story point blank, then filed a complaint, along with other senior officers, against Katz, who found himself forced to face a dozen lawyers determined to defend the honour of the nation’s “heroes”.

Under pressure from the media - who were calling him a “collaborator” and were only covering his accusers’ version of the facts - and the courts, he agreed to sign a document acknowledging he had falsified their statements. Though he withdrew his acknowledgement a few hours later and had the backing of a university commission, the legal proceedings were over.

With the collapse of the Oslo Accords, the return to power of the Likud, the failure of the Camp David Accords and the Taba Summit, the Second Intifada and the kamikaze attacks, Israeli pacifists were no longer interested in the Palestinian version of 1948. Indeed, most were too busy falling into rank to escape the repercussions of the country’s increasingly conservative social order.

Testifying for posterity

In 2005, the filmmaker Eyal Sivan and the Israeli NGO Zochrot developed the project Towards a Common Archive aiming to gather testimonies from the Jewish soldiers of 1948. More than 30 agreed to testify on the events of those days which had been subject to such conflicting accounts.

Why had fighters now agreed to testify, a mere few years later? According to Pappé, the scientific director of the project, for three reasons.

They did all agree on the necessity, in 1948, of forcing Arab populations into exile in order to build the State of Israel

First, most were approaching the end of their lives and were no longer afraid of speaking out. Second, the former fighters had fought for an ideal that had deteriorated with the rise in Israel of religious circles and the far right, as well as the neoliberal electroshock imposed by Netanyahu during his successive mandates.

Third, they were convinced that sooner or later the younger generations would discover the truth of the Palestinian refugees, and they believed it was their duty to pass on the knowledge of the disturbing events.

The testimonies are not identical across the board. Some fighters went into great detail, whereas others did not wish to address certain topics. Nevertheless, they did all agree on the necessity, in 1948, of forcing Arab populations into exile in order to build the State of Israel, though their views differed at times on the usefulness of firing on civilians.

All claim to have received specific orders concerning the razing of Arab villages, however, to prevent the exiled populations’ return.

The villages were “cleaned out” methodically. As they approached the site, soldiers would fire or launch grenades to frighten the local populations. In most cases, such actions were enough to drive the inhabitants away. Sometimes, a house or two had to be blown up at the entrance of a village to force the few recalcitrant inhabitants to flee.

As for the massacres, for some, the acts were merely part of the “cleansing” operations, since the leaders of the Zionist movement had authorised them to “cross this line”, in certain cases. The “line” was systematically crossed when inhabitants refused to leave, put up resistance, or even fought back.

No remorse

In Lod, more than 100 people took refuge in the mosque, believing rumours that Jewish fighters would not attack places of worship. A rocket launcher destroyed their shelter, which collapsed on them. Their bodies were burned.

For others, the leaders Yigal Allon, of the Palmach, and David Ben Gurion, of the Jewish Agency, reportedly opposed the shooting of civilians, ordering forces to first let them go and then to destroy the homes.

The combatants also testify to a contrasting Palestinian response. In most cases, they seemed “frightened” and overwhelmed by the events, hastening to join the flow of refugees. Some Arabs begged the soldiers not to “do to them what they did in Deir Yassin”.

Other inhabitants seemed convinced they would be able to return home at the end of the fighting. One witness spoke of residents of the village of Bayt Naqquba who left the key to their houses with Jewish neighbours in the Kiryat-Avanim kibbutz, with whom they were on good terms, so the latter could ensure that nothing was looted.

Good Jewish-Arab relations come up regularly, and few witnesses speak of being on bad terms with their neighbours before the beginning of the war.

During an eviction around Beersheba, Palestinian peasants came to ask for help from the inhabitants of the neighbouring kibbutz, who did not hesitate to intervene and denounce the actions of Zionist soldiers.

More than 60 years after these events, the combatants expressed little or no remorse. According to them, it was necessary to liberate the territory promised by the UN in order to found the Jewish state, and this meant there was no room for Arabs in the national landscape.

- Thomas Vescovi is a teacher and a researcher in contemporary history. He is the author of Bienvenue en Palestine (Kairos, 2014) and La Mémoire de la Nakba en Israël (L'Harmattan, 2015).

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

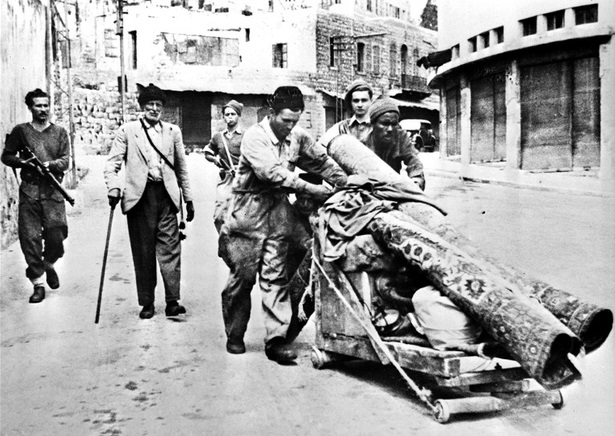

Photo: On 12 May 1948, members of the Haganah escort Palestinians expelled from Haifa after Jewish forces took control of its port on 22 April (AFP).

This article originally appeared in French.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.