Turkey’s LGBT community vows to march for Pride despite crackdown fears

ISTANBUL, Turkey - Turkey’s LGBT community has vowed not to surrender in its battle against homophobia, despite fears the outcome of this week’s election could lead to a further government crackdown.

Amid rising hostility and mounting discrimination, members of the LGBT community feel President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is waging a war against them. Nonetheless, they are preparing to launch a counteroffensive in the form of rainbow flags and a show of unity throughout Pride week, which begins a day after Sunday's vote.

During a stormy afternoon in Istanbul, 24-year-old Marsel Tugkan Gundogdu took cover under the canopy of a cafe in the central harbourside district of Karakoy. It was raining and the water streamed down by the bucketload.

“I’m really excited for pride week in Istanbul, it's going to be big,” he told Middle East Eye.

“Now, it is more important than ever to show solidarity, both for one another within the community and as a show of strength for the rest of the country.”

Homosexuality was decriminalised by the Ottoman Empire in 1858 amid a wave of wider social and political reforms, and has remained legal in Turkey ever since.

But an Amnesty International report earlier this year said that LGBT organisations had reported "a sharp increase in campaigns of intimidation and harassment targeting individuals or planned events".

"The current clampdown on the activities of [LGBT] organisations marks a stark departure from recent years which saw increasing participation in Istanbul Pride events, with tens of thousands attending the last Pride March in June 2014.

The blanket bans on activities threaten the very existence of these organisations and reverse... recent progressive steps to counter prevailing homophobia and transphobia," the report said.

Human Rights Watch has also called on the Turkish government to "actively protect" LGBT people in accordance with international human rights standards.

Lighting up a cigarette, Gundogdu said he first realised he liked men when he was in primary school, but it took him until he was studying at university to fully accept that he identified as a gay man, fearing potential repercussions.

Although he has been involved with Istanbul-based LGBT organisation SPoD (Social Policies, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation Studies Association) since 2013 – becoming a board member in March – he refrained from taking part in the city’s Pride parade last year due to fears of escalating violence. This year things are different. Marsel would, he said with a big smile, be in the middle of the celebrations.

“People describe Istanbul as having this soul and this openness that is unique compared to the rest of Turkey. It used to be like that but since the failed coup attempt in 2016, things have changed, even here,” he said.

'Climate of oppression'

Originally from the port city of Mersin in southern Turkey, Gundogdu moved to Istanbul to study for an English language and literature degree at Istanbul Bilgi University.

Although he considers himself to have had an easier ride compared to many others in the LGBT community, the life story he recalls is mapped around traumatic experiences related to his sexuality, some of them violent.

“Just last year, some friends and I protested a visit from the Turkish Red Crescent to collect blood donations from students at our university campus. We did so because the organisation refuses to accept donations from gay men due to the perception that they have a higher risk of carrying HIV,” he said.

This protest led to an attack on him and his friends by a conservative nationalist group of around 60 students.

“They were all ready to give us a good beating. Even now I have goosebumps just telling you about it,” he explained, taking a couple of drags on his cigarette.

“Myself and six friends were forced to run for our lives - it was like an action movie and not in a good way. It was absolutely terrifying and we were all left totally traumatised.

“After that we were a target. Two of my friends were followed and badly beaten. We all felt unsafe. That week we had final exams but we were too scared to go in,” he said.

'When I attended the parade attempt in 2015, the police intervened. As we ran from the officers we were confronted by conservative locals who were armed with bats and other weapons. This year, we will make sure we are seen and our voices are heard even if they try to stop us'

- Marsel Tugkan Gundogdu, LGBT activist

“Since that day I’ve never felt safe. I graduated two weeks ago and I feel so relieved.”

Gundogdu said the campus once had a reputation as a place where sexual minority groups were welcomed.

“There is a growing climate of oppression and even the safe places aren’t safe anymore. This is why it is so important for us to celebrate Pride Week and to march in solidarity. And we will march in Istanbul on 1 July,” he said.

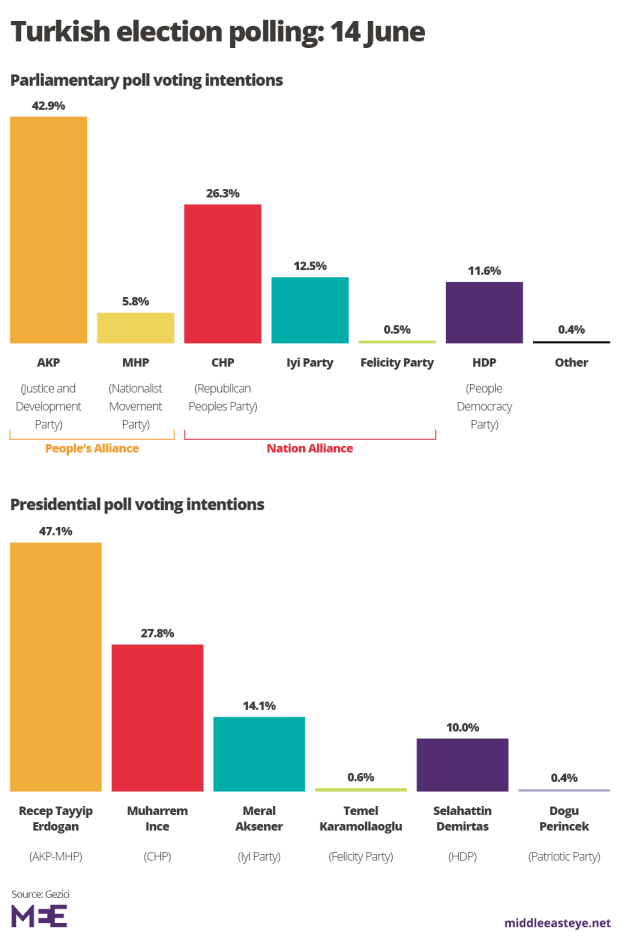

On Sunday, Turkey will vote in both parliamentary and presidential elections for the first time since the executive powers of the presidency were bolstered in a referendum last year. The Republican's People's Party (CHP), which is the main opposition to Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP), has accused the Turkish president of seeking to establish a "one-man regime".

However, the latest polls indicate Erdogan may not get the majority he needs to maintain power in the initial vote and a second presidential ballot could take place two weeks later. There are also indications the AKP may not win a majority in parliament.

Loud silences

None of the presidential candidates have mentioned LGBT rights so far during the election campaign, and the issue seems to have slipped down the agenda, even for parties that highlighted the issue more prominently before the last elections in 2015.

There is no reference to LGBT rights in the AKP's 2018 manifesto, although in the 2015 election it published a leaflet addressing the issue in which the party said it "never had the intention to interfere with anyone's lifestyle".

This time around, it pledges to uphold individual liberties and says: "The free expression, dissemination and propagation of all ideas that are not racist, xenophobic, Islamophobic, sexist or separatist, and mobilisation on the basis of those ideas, is under the protection of our state."

Despite being strong advocates for sexual minority groups’ rights in the previous election, both the CHP, which describes itself as a "modern social democratic party", and the generally more left-wing People's Democratic Party (HDP), have significantly reduced their focus on these issues this year.

The CHP’s manifesto does not use the term LGBT but it states: "We will never allow discrimination based on culture, belief, language, identity, political opinion, gender, sexual orientation and lifestyles."

Meanwhile, although the HDP pledges to address the struggles faced by the LGBT community, the topic has had far less attention throughout its manifesto compared to the previous election.

Istanbul’s Pride Week is due to kick off on Monday, a day after the initial vote. Big plans have been put in place to ensure the week is filled with workshops, panels and picnics on a whole range of topics from sexual reproduction rights to LGBT refugee rights. The hope is for the week to culminate in a parade on Sunday.

But an official Pride parade has not successfully taken place in Istanbul since 2014 and attempts since then have been met with armed resistance from both police and Turkish citizens.

Ban on public gatherings

Since the failed military coup attempt in 2016, the entire country has also been under a state of emergency. This prolonged status has given Erdogan and his cabinet sweeping powers, which many critics say have reduced democratic freedoms throughout the country.

One element has been to impose bans or restrictions on public gatherings – a factor that has hit the LGBT community very hard. An official ban on all LGBT cultural events in Ankara – the country’s capital city – last November, on the grounds of protecting public order, has been adopted by other cities around Turkey.

“There is homophobia and transphobia in society but that is something we feel we can fight. However, the state of emergency is something we feel helpless against,” says Marsel Gundogdu. “It’s important to march during this time.

“When I attended the parade attempt in 2015, the police intervened. As we ran from the officers we were confronted by conservative locals who were armed with bats and other weapons,” he adds.

“This year, we will make sure we are seen and our voices are heard even if they try to stop us.

Gizem Derlin, a 30-year-old transgender man who lives in Mersin – Gundogdu's hometown - said that LGBT people there had to resort to defending themselves from attack.

“On 8 July the fourth Pride Parade will take place in Mersin,” says Gizem. “Last year we were attacked but the police did nothing to help us - we had to defend ourselves. We are frightened but we all know how important it is to stand together."

Gizem was forced to hide his true identity for four years when he worked as a teacher. He is now studying for a master's degree in Gender Studies.

“I felt completely oppressed and like I was living a lie. But transgender people don’t find work easily and the worry of losing my job was too serious,” he said.

“Living in Turkey as someone who is transgender is tough and living in a small city means you are noticed more easily. Mersin is a more cosmopolitan city though and there is a strong LGBT community here which means we have a good support network.”

However, he said even a simple task like catching the bus can be traumatic.

Erdogan has publicly condemned the LGBT community and said anyone who supports its members is going “against the values of the nation”.

'We are playing the long game'

Being a part of the LGBT community can be even more difficult for people who live in Turkey’s southeastern region, where cultural and religious attitudes are generally more conservative than in other areas of the country.

Keskesor Amed LGBT is an organisation that offers the LGBT community in the southeastern city of Diyarbakir a safe place to meet in secret.

Campaigners there told MEE it was important to stay in Diyarbakir rather than "running away" to another city.

“Istanbul is an easier place to fit into if you are part of the LGBT community. But we are playing the long game instead of running away. We hope to make a change here,” said Atalay Gocer, who runs the organisation.

“We organise events without being too visible. This is important in terms of our mental health because it is demoralising for people when they’re not able to do anything.”

The organisation has repeatedly been the target of a harassment campaign by religious groups and some of its members have even had their names, photographs and addresses publicised around the city. Yet they say staying put and showing a united front is the only way to create change.

“We worry the current situation could get worse if Erdogan wins. He is allowing people to feel it’s acceptable to speak openly against the LGBT community,” said Atalay.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.