‘We cannot hide from air strikes’: Life inside the besieged city of Hodeidah

HODEIDAH, Yemen - The air of suspicion that hangs over Hodeidah is palpable as soon as you reach the outskirts of the besieged Yemeni city.

Armed Houthi fighters, dressed not in military uniform but in everyday clothes, patrol checkpoints near the entrance to the port city. They chew qat leaves, the country’s favourite narcotic, or listen to Houthi songs. Some look not much older than children.

Every car on the road from Sanaa is flagged down and its driver and passengers questioned. And not just once: a vehicle can easily be stopped 10 times on its journey into the city.

Faces are examined. ID cards are checked. "Who are you? Why have you come here? What do you do for a living?" Anyone who admits to being a journalist is arrested for further investigation - only reporters sympathetic to the Houthi rebels, who control Hodeidah, can enter.

Every car on the road from Sanaa is stopped and its driver and passengers questioned... 'Who are you? Why have you come here? What do you do for a living?'

The pro-government coalition, which is trying to take the city, imposed a blockade in early November 2017, after a Houthi missile targeted Saudi Arabia.

It has since been partially lifted, but access to the port - the main aid and goods pipeline for almost 70 percent of Yemen's imports - is still limited. It is an essential gateway in a country where two-thirds of the 28-million-strong population is dependent on aid to survive.

Houthi military vehicles stream out of the city alongside cars full of families desperate to escape. There are also trucks, carrying supplies towards Sanaa and other provinces, but in fewer numbers than a year ago.

The bustling streets fall quiet

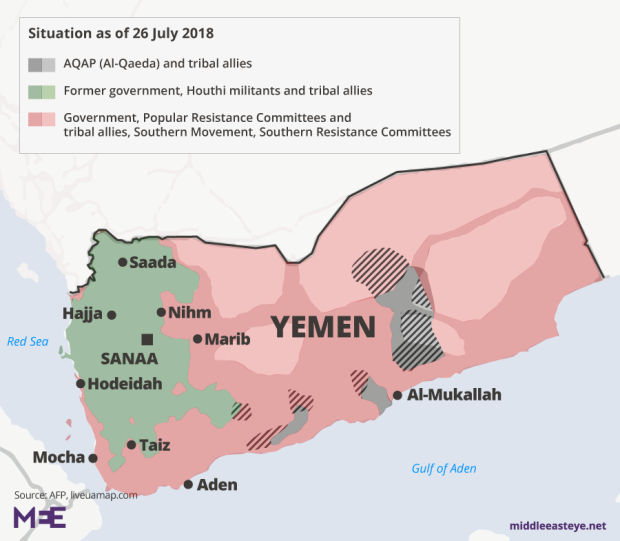

The battle for Hodeidah, which has been held by Houthi forces opposed to the Yemeni government since 2015, began in June 2018, when Saudi-led forces and their allies announced the start of Operation Golden Victory.

The fighting has since ground to a halt, as the Houthis dig in to defend the city, laying landmines and installing gun placements. The UAE, one of the key members of the coalition, suspended its military advance in early July to support UN efforts to broker a peace deal.

The coalition, which is operating the only air force in the war, denied it was responsible.

Only days earlier, the UN said air strikes outside the city had hit a water plant which supplies most of Hodeidah’s water. "These air strikes are putting innocent civilians at extreme risk," the statement said.

The atmosphere of suspicion so evident at checkpoints is also conspicuous on the streets of the city.

During the past few months, fighters from other parts of Yemen have come to Hodeidah, most of whom support the Houthis. Residents assume new arrivals are there to fight unless they can prove otherwise.

This atmosphere of mistrust is unusual in what was a friendly city until the war began in March 2015.

But that night-time bustle is now absent. Instead the streets are almost empty of pedestrians when it becomes dark and are outnumbered by the few passing Houthi vehicles.

Hothaifah Nouri, 38, a resident, said: "We buy our commodities during the day. After 8pm we do not leave our homes and stop our children from leaving."

Anyone who ventures out at night is liable to be arrested and questioned by the Houthis; those with a valid reason, such as a medical emergency, are free to go.

The only noises during darkness, aside from air strikes, are the Houthis, whose shouts echo through the empty streets amid the continual rumble of their military vehicles.

"We live amid war," Nouri said. "No one dares to go on to the streets at night in case he becomes a suspect and puts himself in danger."

Fear amid the raids

The residents of Hodeidah have adapted to the rival sides in the conflict fighting on the ground.

Battles are usually too far away to be heard: if they come close to a neighbourhood then there is usually sufficient time for civilians to take shelter.

Instead it is the air strikes, with the scream of fighter jets and shockwaves from explosions, which leave people living in fear.

Slim and pale, he speaks with anger about the air raids. "If the clashes come to our neighbourhood,” Mizgagi said, “then we can hide in the basement. But we cannot hide from air strikes as they destroy the whole building.”

Residents listen nervously at their windows to try to determine the locations of the explosions.

Last Thursday afternoon, just days after this interview, 26 people were killed when the fish market was hit by what is believed to be an air strike. "When we hear the air strikes at night, we feel that we will become the next target,” said Mizgagi. “Many people have fled the city. I believe the Saudi-led collation does not care about civilians, so they target them with air strikes everywhere."

'I hope the battles do not come near the port because closure will lead to a humanitarian disaster'

- Saad al-Deen al-Siwari, customs broker

Some parts of Hodeidah have been less affected by the raids than others.

Saad al-Deen al-Siwari has been a customs broker in Hodeidah’s port for nine years. Between mouthfuls of qat he explained that the Saudi blockade earlier this year did affect imports, but trade into the port has picked up again over the past two months.

"The battles are far from the port, and they cannot affect the work of the port or the movement of trucks among the provinces. The port is still playing a main role in the import of basic items."

But he still feared for the future. "I hope the battles do not come near the port because closure will lead to a humanitarian disaster," he said.

Returning to the war zone

For many residents of Hodeidah that disaster has already happened.

The UN said that as of 29 July it had registered 48,574 households from Hodeidah province as displaced and distributed 40,393 rapid response mechanism kits, which contain essential supplies including food and sanitation supplies.

But others are choosing to return after their hopes for a better life away from the fighting have failed to materialise.

Adnan Abdurrahman, 38, a father of four, fled Hodeidah in early July towards Sanaa. Now he has come back."When I travelled to Sanaa, I gave up my work as a driver of a minibus in Hodeidah,” he said, “but I could not rent a house in Sanaa.

“So I resorted to living in a camp of displaced people, where the whole family lived in one room. There was not enough food and the room was too small."

He and his family have decided to stay in their home city, regardless of what happens.

Hothaifah Nouri complained that the opposing sides in the conflict did not take civilians into account, demonstrated in fierce fighting across several Yemeni cities, including Hodeidah.

But he said that despite this, many of those who had fled the city found conditions not all that much better outside.

“It is very hard to live as a displaced person, waiting for people and organisations to help you. I will not flee my house even if the war kills me.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.