Bin Salman's dark and tangled web: How Saudi prince looms over the Middle East

The death of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi on 2 October has thrown a global spotlight on the approach and actions of Mohammad bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, Saudi Arabia's crown prince.

After admitting that Khashoggi died in its Istanbul consulate, Riyadh has sought to distance the kingdom's de facto ruler from the killing of the Washington Post writer, a critic of the government who was once close to royal circles.

But his death has created bin Salman's biggest foreign policy crisis so far and thrown a spotlight on his leadership and ambitions.In the short time that he has been on the global stage, bin Salman managed to cultivate the image of a driven operator, be it directing the war in Yemen, pushing Donald Trump's peace plans with the Palestinians, leading the blockade against Qatar or purchasing land from Egypt to expand Saudi's economic opportunities.

Neither his allies nor his enemies can be in doubt of what he thinks of them - and how they fit in with his vision for Saudi Arabia's future.

1. The United States: Backer of Trump

Two months later, Trump visited Saudi Arabia on his first foreign trip as president and returned to Washington boasting about $110bn secured in weapon deals.

In June 2017, bin Salman toppled his cousin Mohammed bin Nayef to become crown prince and the kingdom's de facto ruler on behalf of his father, who has Alzheimer's disease. Since then, bin Salman has built a personal rapport with Jared Kushner, Trump's son-in-law and senior adviser.

Kushner made an unannounced trip to Saudi Arabia in October 2017, just days before bin Salman embarked on a widespread purge, locking up journalists, businessmen, Islamic scholars and fellow royals.

In spring 2018, bin Salman spent weeks in the US, meeting with politicians, tech executives and celebrities. Appearing with bin Salman at the Oval Office in March, Trump held up a blue poster featuring what he said were Saudi arms deals which would create jobs in the US.

Trump has subsequently used his relationship with Saudi royals to send a message to his supporter base. Earlier this month, he told supporters at a rally in Mississippi that the Saudi government "might not be there for two weeks" without US protection. Bin Salman called the remarks a "misunderstanding".

2. The economy: Vision 2030 and Aramco flotation

Its over-arching aim is to create the world's largest public investment fund (PIF), estimated to be worth $2 trillion, interest from which would be reinvested and deliver constant profits.

Launched by bin Salman in April 2016, its key proposals included selling off stakes in major assets such as King Khaled Airport and the construction of a $4bn international resort on the Red Sea coast.

Most significant is its proposal to sell five percent of Aramco, the world's largest oil producer, which it is hoped could bring in up to $2 trillion.

Stock exchanges vied to host the largest stock listing in history. In July 2017, the UK's financial regulator announced it would loosen regulations to allow five percent of Aramco to list on London's stock exchange within its "premium" listing rules, which would usually exempt state-owned companies.

The Financial Conduct Authority denied the changes were linked to Aramco - but they were made months after Theresa May, the UK prime minister, and Xavier Rolet, the then-head of the London Stock Exchange Group, travelled to Saudi Arabia to lobby.

In August 2018, Riyadh denied reports that the flotation had been suspended. In October 2018, bin Salman told Bloomberg: "I believe late 2020, early 2021. The investor will decide the price on the day. I believe it will be above $2 trillion. Because it will be huge."

3. Israel: Weapons, spyware and mega-cities

Bin Salman has quietly fostered closer ties with Israel, taking a particular interest in Israeli cyber-surveillance technology and hi-tech weaponry as well as thawing relations between the two intelligence communities.

In September, Saudi Arabia was reported to have cut a deal though US mediation to buy Israel's Iron Dome missile defence system to deploy along its border with Yemen. Israel denied any such deal had been signed.

Israeli tech firms are also reportedly in talks with Saudi Arabia that could see them set up operations in Neom, bin Salman's proposed $500bn "mega-city of the future," while Saudi Arabia's intelligence services are reported to be using Israeli spyware to spy on dissidents in other countries.

In November 2017, Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz said that the country had had covert contacts with Saudi Arabia, a first disclosure by a senior Israeli official of such dialogue. Both Saudi Arabia and Israel view arch-foe Iran as the main threat to the Middle East: the speculation is that shared interests may push Saudi Arabia and Israel to work together.

Historically, Saudi Arabia maintains that any relations with Israel hinge on Israeli withdrawal from Arab lands captured during the 1967 Middle East war.

But Steinitz said: "The contacts with the moderate Arab world, including with Saudi Arabia, help us to stop Iran. When we fought to get a better nuclear deal with Iran, with only partial success, there was some help from moderate Arab countries vis-a-vis the United States and the Western powers to assist us in this matter and even today, when we press the world powers not to agree to the establishment of an Iranian military base in Syria on our northern border, the Sunni Arab world is helping us."

A week prior to that, Israeli military chief Lieutenant General Gadi Eizenkot told an Arabic language online newspaper that Israel was ready to share "intelligence information" with Saudi Arabia, saying their countries had a common interest in standing up to Iran.

In another sign of goodwill, in March Saudi Arabia agreed to start allowing flights to Israel from India to pass through its airspace.

4. Palestine: Salesman for Trump's 'deal of the century'

Last December, as Trump announced that Washington would recognise Jerusalem as Israel's capital, bin Salman summoned Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas to Riyadh to tell him that the unpublished US plan was the "only game in town".

Abbas subsequently denounced the deal, rumoured to include the Palestinians' giving up their sovereignty over occupied East Jerusalem and renouncing the right of return for refugees, as the "slap of the century".

Speaking in New York in April, bin Salman countered that Palestinians should come to the negotiating table or "shut up and stop complaining". PA relations with the White House have continued to deteriorate, culminating in the US shutting down the PA's office in Washington in September.

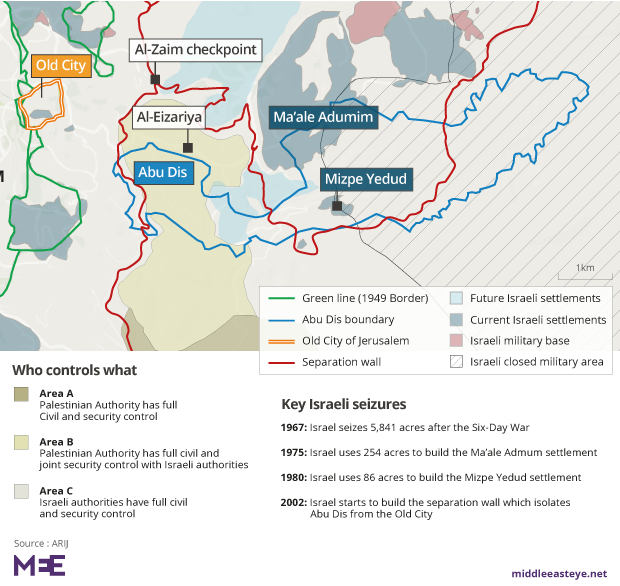

Bin Salman is reported to have suggested that the Palestinians should accept Abu Dis, a fragmented suburb of East Jerusalem, as their capital, effectively undermining King Abdullah of Jordan's status as the custodian of Jerusalem's holy sites.

Saudi Arabia has also been accused of seeking to change the facts on the ground in Israel's favour by refusing to recognise temporary travel documents used by Palestinians in occupied East Jerusalem and Lebanon, requiring them to apply for PA passports in order to travel to undertake the Hajj or Umrah pilgrimages, a measure that could force many thousands of Palestinians to accept papers that could undermine their rights as refugees.5. Jordan: Left out in the cold

1. Riyadh's growing rapprochement with Israel and the US has sidelined Amman, which has often acted as a broker in the region. Trump's much-vaunted "deal of the century,", the details of which have yet to be revealed, has damaged any hopes Amman had of a two-state solution between Israel and Palestine.

2. Saudi Arabia, a senior official close to the Jordanian royal court told Middle East Eye in November 2017, has been trying to woo Israel by offering concessions on Palestinian refugees, which Amman fears could endanger the stability of the Hashemite kingdom.

In December 2017, bin Salman ordered King Abdullah of Jordan to buy into Trump's strategy, despite the protests of the monarch, who rules a kingdom where two-thirds of the population is of Palestinian descent. No surprise then that in April 2018 King Abdullah refused to shake hands with bin Salman during the Arab League summit in Dharan.

The source who spoke to MEE also said that the Royal Court in Amman was concerned by the pressure being applied on Jordan to join an anti-Iran campaign and the potentially dire consequences of what it considers "reckless" Saudi policies.

3. Jordan has suffered through the economic blockade of Qatar, with less trade passing through its key port of Aqaba as Iraq and other countries began to use Saudi ports in the Red Sea. The Jordanian government has also said that promises of aid from Saudi Arabia in compensation have yet to arrive.

4. Amman was upset at not being consulted about Saudi plans for Neom, which will extend into Jordan. The suspicion is, one source said, that the primary beneficiary in the city's construction will be the hi-tech industries of Israel.

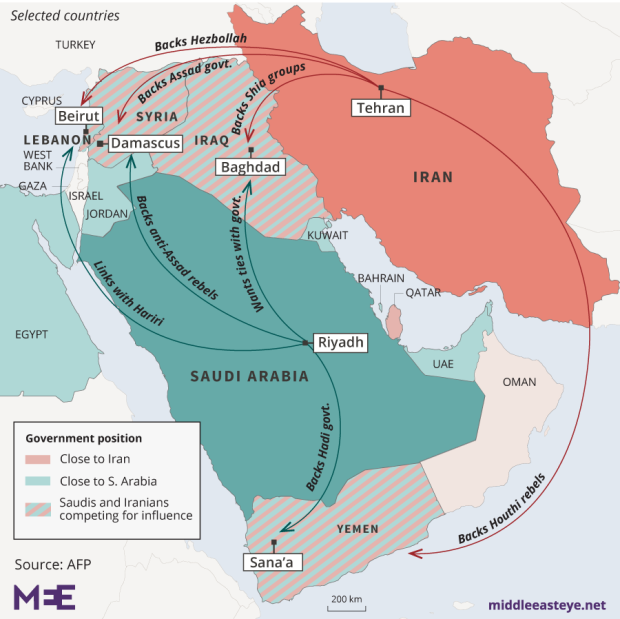

6. Iran: Cold War and the arch-rival

Tehran and Riyadh have been regional rivals for decades. Tension increased in the late 1970s when Iran became an Islamic Republic following the overthrow of the shah and is now best described as being in a state of cold war.In recent years, that rivalry has played out in Yemen and Syria, where the kingdom and the Islamic republic have backed opposing sides in the respective conflicts.

Meanwhile in Lebanon, Tehran has supported Hezbollah, while Riyadh has put its weight behind Prime Minister Saad Hariri.

Riyadh has also said it opposes any plans for Tehran to become a nuclear military power. In March 2018, bin Salman warned that the kingdom might be forced to develop its own weapons: "Saudi Arabia does not want to acquire any nuclear bomb, but without a doubt if Iran developed a nuclear bomb, we will follow suit as soon as possible."

In September 2018, an attack in Ahvaz, the capital of Iran's oil-rich southwestern Khuzestan province, left at least 29 people dead and 70 others wounded.

Less than a week later, in a fiery speech to worshippers at Friday prayers in Tehran, in reference to the Saudis and Emiratis, Brigadier General Hossein Salami of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) said: "You are sitting in a glass house and cannot tolerate the revenge of the Iranian nation."

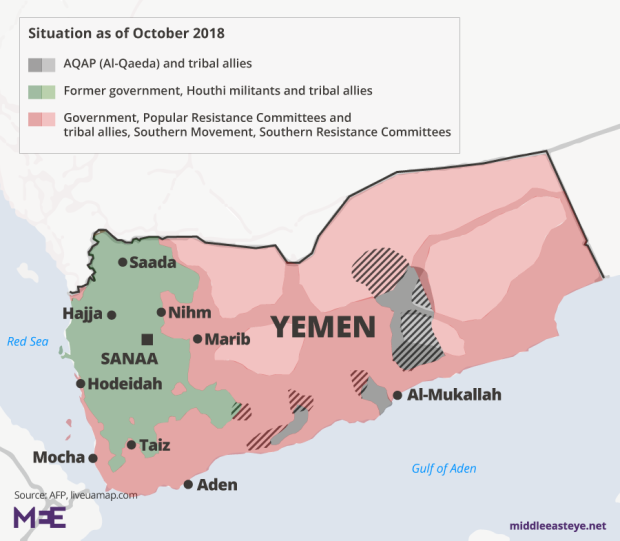

7. Yemen: Bloodshed over the border

The ongoing war has now killed an estimated 10,000 Yemenis, with millions more displaced. Human rights organisations have accused the Saudis of indiscrimimate bombing, including an air strike on a funeral hall in October 2016 that killed at least 150 people and one on a bus in August 2018 that killed at least 50 people, including 40 children.

The World Health Organisation has reported that an outbreak of cholera, the worst in the world, is now running at about 10,000 cases reported every week, double the rate of the first eight months of 2018. The UN warned in October 2018 that if the conflict continued an estimated 12 to 13 million civilians would be at risk of starvation.In January 2016, in an interview with The Economist, bin Salman denied he was the architect of the Yemen operation, saying the launch of the campaign had nothing to do with his appointment and had been supported by the UN. "This has nothing to do with the fact that I became minister. It has everything to do with what the Houthis did."

8. Syria: Backing the rebels

In April, the crown prince acknowledged that Assad was going to stay in power. "I believe Bashar [al-Assad] is staying for now,” he told Time magazine. "And Syria has been part of the Russian influence in the Middle East for a very long time. But I believe Syria's interest is not to let the Iranians do whatever they want in Syria for the mid-term and long-term because if Syria changes ideologically then Bashar will be a puppet for Iran."

But the crown prince still wants Trump to keep US forces in Syria and has expressed a willingness to send a Saudi force to maintain stability, should the US decide to pull out (the kingdom has taken part in air strikes against Islamic State targets operating within Syria).

The kingdom has also given $100m to rebuild areas controlled by the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which Turkey considers a terrorist organisation.

In June, Turkey's Anadolu Agency reported that Saudi military consultants met with forces of Al Sanadid, an Arab militia that operates under the aegis of the SDF, at the US base in Kobani.

9. The Gulf: Building an Arab NATO

White House sources indicated that the initiative would act as a "a bulwark against Iranian aggression, terrorism, extremism, and will bring stability to the Middle East".

It would also cover counterterrorism, missile defence and military training, as well as strengthening economic and diplomatic ties.

The Gulf States have shown increasing coordination in recent years, including against protests in Bahrain (2011), the war in Yemen (2015) and sanctions against Qatar (2017). In each case, the UAE has been a steadfast ally of Riyadh.

In May 2017, the US and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) met in Riyadh. President Trump, Saudi’s King Salman and Egypt's President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi inaugurated the Global Center for Combating Extremism in Riyadh by putting their hands on an illuminated globe.

An agreement was also signed between the GCC and Washington to coordinate their efforts against the financing of terrorist groups. Weeks later, the blockade of Qatar, for which the GCC was a core supporter, began: one of the accusations against the emirate was its alleged backing of terrorism, which it denies.

10. Qatar: Leading the blockade

The coalition alleged that Doha supported terrorism through its support for the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as a number of rebel groups in Syria and had become too close to Iran, Saudi's regional rival.

The GCC ordered all their citizens to leave Qatar, while Saudi Arabia among others gave Qatar citizens and visitors two weeks to leave the kingdom. Qatar said that the move undermined its sovereignty.

By July, the Saudi-led group had issued 13 demands and a deadline to Qatar, including that it cut ties with Iran, halt construction of a Turkish military base and stop funding media outlets including Al Jazeera and Middle East Eye (MEE does not receive funding from Qatar).

The Qataris refused and the blockade continued.

Tension has simmered ever since: in August, Qatar accused Saudis of barring Hajj pilgrims, which Riyadh denies. In June, it was reported that Saudi Arabia had threatened the emirate as it sought to acquire a Russian missile defence system. Riyadh has also hinted that it wants to build a canal that would physically turn Qatar into an island - including a nuclear dump.

11. Lebanon: The PM who resigned, then didn't

In November 2017, Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri was summoned to Riyadh, from where he made a shock annoucement that he was resigning. Observers believe this was as punishment for his apparent inability to counter Hezbollah.

For nearly two weeks, Hariri remained in Riyadh - although he has publicly denied being held against his will - before he left after France put pressure on the kingdom. He then rescinded his resignation.

Hariri has since met with bin Salman and King Salman on several occasions, fueling speculation that Riyadh is still financially influencing the prime minister's Future Movement party, which it has long backed. In April, Saudi Arabia renewed a $1bn credit line to Lebanon.

Hezbollah accused Saudi Arabia of trying to interfere in legislative elections in May by reviving the anti-Iranian March 14 political alliance, allegations that Riyadh has denied.

But Hariri dismissed interior minister Nouhad Machnouk, while his chief of staff and cousin Nader Hariri quit: both men are reportedly regarded unfavourably by Saudi Arabia.

12. Khashoggi death

After multiple denials, Saudi Arabia confirmed on 19 October that Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist, had been killed inside its consulate in Istanbul.

In a statement on Saudi state television, the country's chief prosecutor said a fight broke out between Khashoggi and "people who met him" in the consulate. The brawl resulted in Khashoggi's death, the prosecutor said.

Bin Salman insisted earlier this month that Khashoggi had left the consulate. "Yes. He's not inside," he said in an interview with Bloomberg published on 5 October. "My understanding is he entered and he got out after a few minutes or one hour."

Multiple sources within the Turkish authorties say that he was murdered on the orders of bin Salman. Khashoggi was once part of the Saudi establishment. But in recent years he had become critical of the kingdom's rulers, and in September 2017 moved to Washington amid fears of a new crackdown on dissenting voices.

Other information released by the Turkish authorities, including CCTV images, suggested members of bin Salman's security detail were in Istanbul on the day of Khashoggi's death.

The kingdom has been the target of global criticism, including from allies in Europe. One casualty has been the Future Investment Initiative conference, intended to showcase bin Salman's Vision 2030 economic strategy to global players. It has suffered multiple no-shows, including Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world's largest fund manager, and IMF chief Christine Lagarde.

13. Egypt: Buying islands and land

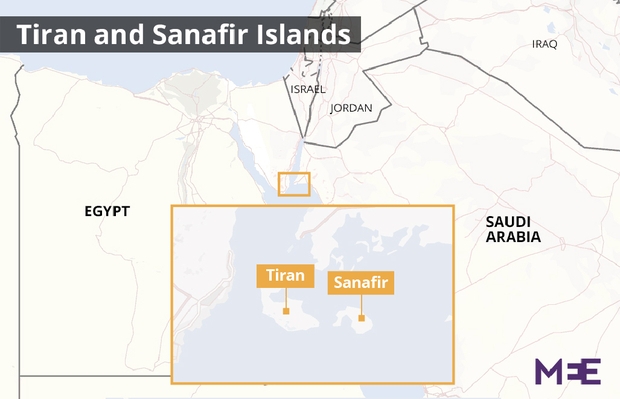

During a visit by King Salman ben Abdel Aziz to Egypt in April 2016, the two countries signed economic agreements worth approximately $25bn. Part of the deal included the sale to Riyadh of the two strategic Red Sea islands of Tiran and Sanafir, which sparked protests across Egypt (Saudi Arabia hopes to use them as part of a bridge between the two countries).

Riyadh has extended its economic ties even more since bin Salman became crown prince in 2017.In March 2018, Cairo and Riyadh signed a $10bn agreement to develop Neom, a cross-border mega city project launched by bin Salman as part of his Vision 2030 strategy to diversify the kingdom's economy. Some of the project will be built in the southern Sinai on land which Saudi will rent on a long-term lease.

Egypt has backed Saudi's blockade on Qatar and supported the kingdom in its diplomatic spat with Canada.

But the two nations are apart on the war in Yemen, in which Cairo has refrained from participating, and on Syria, where Egypt has said it backs the armed forces of President Bashar al-Assad as key to the country's stability.

14.Turkey: Point on the 'evil triangle'

While relations appeared to have improved with the accession of King Salman in January 2015, they splintered again after a Saudi-led coalition of Arab states states blockaded Qatar, another ally of Turkey, in June 2017. The Middle East has since echoed to a war of words between bin Salman and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan

In March 2018, the Saudi crown prince accused Turkey of being part of a "triangle of evil” along with Iran and "terrorist organisations" and said the president was looking to recreate the Ottoman Caliphate.

Al-Shorouk, an Egyptian newspaper, quoted the crown prince as saying "the contemporary triangle of evil comprises Iran, Turkey and extremist religious groups".

Erdogan, for his part, accused bin Salman in November 2017 of trying to "weaken Islam" through his attempts to introduce a "moderate" version of the religion and said that the crown prince did not have exclusive ownership of the religion.

"They [the Saudis] say we will return to moderate Islam, but they still don't give women the right to drive," Erdogan said. "Is there such a thing in Islam?" Riyadh eventually lifted the driving ban in June 2018.

15. Iraq: Will it come into Riyadh's political orbit?

The kingdom has long wielded influence over several pro-Saudi Iraqi politicians. But many observers were still shocked when, in July 2017, bin Salman met in Riyadh with Muqtada al-Sadr, a popular Shia cleric, former resistance leader and frequent critic of foreign states trying to pull political strings in Iraq.

Many Iraqis despise Saudi Arabia, which they believe was behind the rise of Islamic State in the Iraq: rumours of a visit by bin Salman in March 2018 sparked mass demonstrations across Baghdad.

The US has long hoped that money from Saudi Arabia would be able to support reconstruction of Iraq: Abdul Aziz Al Shimmari, the Saudi ambassador to Baghdad, has promised that a border crossing between Saudi and Iraq would soon be reopened.

Reports also suggest that negotiations are ongoing for Saudi to alleviate the water and electricity crisis in Basra - a province heavily dependent on Iran for its electricity.

In May 2018, Riyadh paid $300m in cash to Iraqi politicians to boost their chances in the final weeks of the election, two Iraqi sources familiar with the transactions told MEE, to prevent Iranian-backed candidates from coming to the fore.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.