'Leaving hell to live in hell': The bribes and checkpoints from Gaza through Egypt

GAZA STRIP - Scraps of cardboard, bags or the bare floor are where travellers rest their heads on their way through Rafah, the border crossing that has become the only functioning portal between blockaded Gaza and the outside world.

They find little in the way of water, food or respite from the heat on the first leg of a journey through Egypt thousands have made in recent months, where they face treatment many say is humiliating: long hours spent in a series of humid, neglected waiting rooms and days on stuffy buses through the sweltering desert.

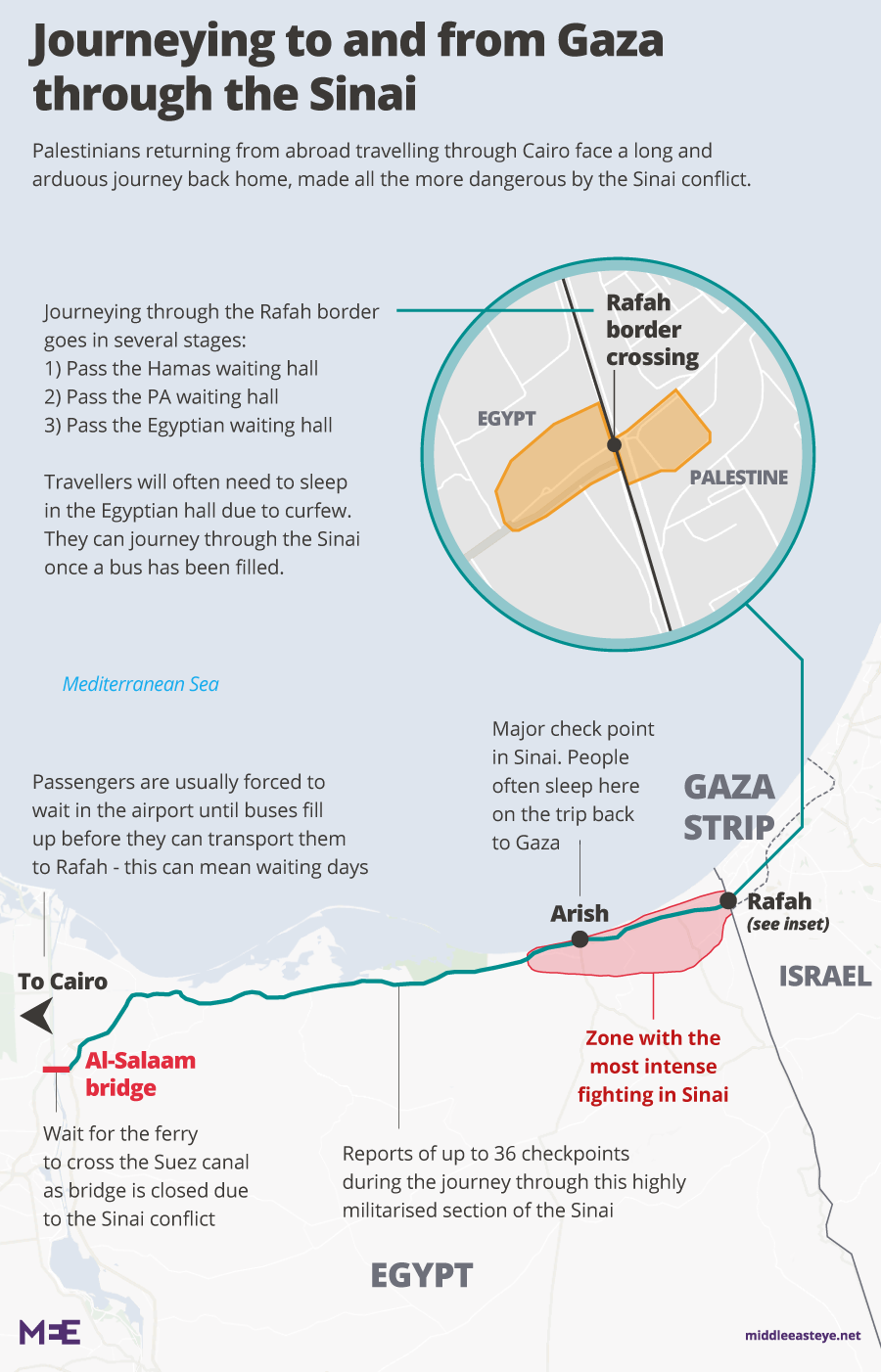

To leave the Gaza Strip, its Palestinian residents spend almost a day in Rafah before buses carry them through the Sinai desert, then cross the Suez Canal by ferry and onwards to hospitals in Egypt, while some use Cairo as their gateway to healthcare or studies or work further afield.

In reality, the process is not so smooth; it stutters and stalls and very few ever come close to actually making the trip anyway, frustrated at the first stages because the border is usually closed and the waiting lists to get across too long.

It feels like crossing an enemy's territory

- Ibrahim Ghunaim, Palestinian

The way to skip those lists is to pay someone, usually on the Egyptian side. Those bribes have become increasingly common over the past six months, when the border has been open for periods unprecedented in recent years, encouraging Palestinians leaving Gaza, and those hoping to return, to make the crossing.

“The people who want to leave Gaza – they left hell to live in a hell in the Sinai desert,” says Ibrahim Ghunaim, a Palestinian rapper who left the blockaded enclave to focus on developing his craft, stunted in Gaza by his inability to travel for performances.

Crossing the desert took him four days of waiting at and passing through checkpoints in the barren and militarised Sinai.

“It feels like crossing an enemy's territory.”

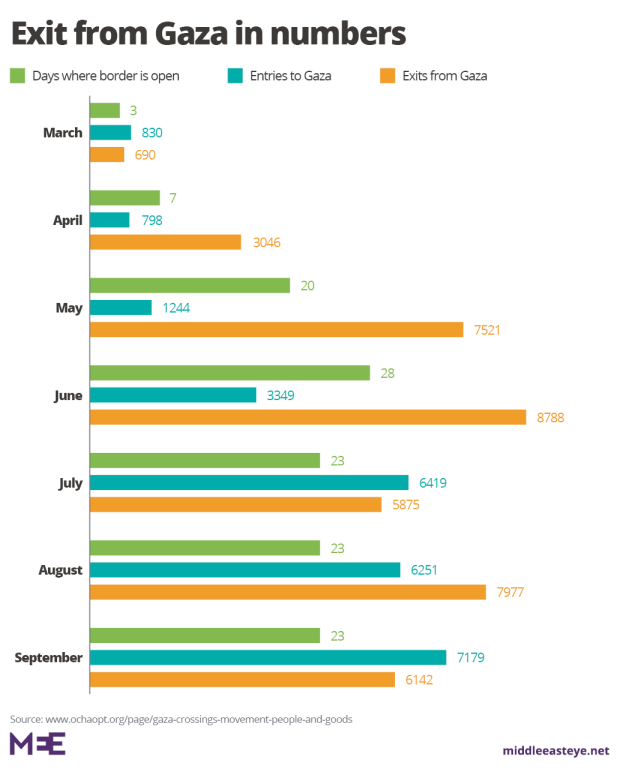

Since May the border has mostly remained open; a total of 133 days compared to 36 during the whole of 2017. The number of people crossing both ways has increased with every month, from 1,500 in March to more than 14,000 in August.

A catalyst for the change was the Great March of Return, weekly Friday protests since late March seen as the culmination of the pressure felt by young Palestinians in Gaza, where unemployment is more than 50 percent and electricity runs for less than four hours a day.

More than 200 Palestinians have been killed and thousands wounded during those protests, when Israel has routinely deployed snipers with live fire and used tear gas and rubber-coated bullets.

The living dead

The cast on Arafat Abdo’s foot and the crutches he hops around on mean he is regularly mistaken for one of Gaza’s thousands of walking wounded - the protesters shot in the leg with a sniper’s bullet. He actually simply sprained his ankle but the injury makes a big difference to him as a hip-hop dancer, a career path he already struggled with in Gaza.

He meets with his friends in the middle of Gaza City, in a hall of flaking paint, coffee and card games near a former prison once operated by all of Gaza’s recent rulers - Britain, Egypt, Israel and then Hamas - until it was bombed out in the 2008 war by Israeli forces. They are all part of the same creative collective of dancers and artists and they all feel their talents are wasted in the enclave.

“The main thing I want right now is to leave Gaza,” says Abdo. Graduates find jobs in short supply and alternatives, like his dancing, do not always find cultural acceptance.

“People don't understand it, they ask ‘what do you do?’"

The reasons for leaving are varied. Many are students who have won places at universities abroad and even confirmed visas but have not been able to leave Gaza, while others travel for work or medical treatment. Some however are simply lured by the idea of opportunity beyond the border, even when they have nothing lined up.

“There is a generation of youth, their souls are destroyed. They don't want to offer anything to society because they have nothing to offer,” said Abdo’s friend, Mojahed Elsusi.

Their collective, called al-Watan, or the nation, created a play around the concept of the enclave’s population as mummies because, they said, “the people inside Gaza are the living dead”.

The recent opening of Rafah and the informal bribe-based system suits many of them. The formal waiting list run by Gaza’s interior ministry is weighed down by high-priority medical cases that make it hard for many of the most desperate, including some of the long-term ill, to exit.

The only other alternative is the Israeli-run Erez crossing. Officially, it is more regularly open but only to certain people. Permits are mostly issued for health reasons or in some cases for businessmen or Palestinians employed by international agencies. In reality, the numbers of all types of permits have dwindled in recent times.

Some have been rejected on the basis of being related to Hamas members and there have been several high-profile arrests of people already granted permits who are apprehended while crossing through Erez, including senior aid workers in international organisations.

The sense that Erez is almost impassable for most of Gaza’s population has made Rafah all the more important in the collective imagination. Talks involving Hamas, whether with Israel, the rival Palestinian Authority or before that the exiled strongman Mohammed Dahlan, have often teased the opening of Rafah.But years of talks have never delivered on that promise and instead Gaza’s travellers have had to wait for the limited days when the border has been opened and on the system of payments that increase the chances of getting through.

“Even if I have to collect garbage from the streets for a year to raise the money, I'll do it,” says Elsusi.

The 'coordination'

Detailing how they left Gaza, travellers come quickly to the topic of the tanseeq, or “coordination”, their way of alluding to the bribes that ease the crossing through Rafah.

The money is collected by mediators in Gaza, an anonymous travel agent who works near Rafah and has facilitated some of these payments explained to Middle East Eye, then transferred to Egyptian officers they are in contact with. Sometimes the intermediaries are travel agents, at other times people who simply have the right connections.

“He didn’t have an office for tourism but he had an office selling doors and glass. But it was [actually] for travel,” said Mahmoud*, describing how he was directed to a man who could help him get through Rafah, having had to twice miss out on fellowships because the border had been closed.

He negotiated a payment of $1,200, down from the $1,500 that has become the average rate. Some reported paying almost double that, especially in the early days of Rafah’s opening, when travellers were still unsure about whether there would be enough time to get out, and the travel agent confirmed payments in the past of up to $4,000.

The length of Rafah’s opening has encouraged more like Mahmoud to get out of Gaza. When the large sums required are beyond their means, they borrow it or sell off belongings to make their escape.

“I actually didn’t have $1,200 but I borrowed like $500 from my friend and until now I really haven’t been able to give it back to him,” he said.

Mahmoud said he feared the whole process and disliked that it was illegal but had no choice unless he gave up his final opportunity to take up the fellowship. Many Gazans feel the same, which has helped the informal system to flourish.

"It's not affordable, it's a big [amount of] money, [but] it's essentially been accepted to pay that because people are in extreme need to travel abroad, because they are very sick, because they are about to lose a scholarship or a permit to work abroad," an official for an international agency, who was not cleared to speak to media, told MEE.

But there are also concerns about what impact that process is having on other travellers, who cannot afford to pay and have to rely on the formal process implemented by Hamas.

An October report by the United Nations’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) highlighted that after months of increased access at Rafah the number of people on the waiting list had remained at 23,000, only a 7,000 reduction from the previous figure.It described the official procedures at the border as “confusing and obscure” and pointed out that people who had been registered for more than eight months were still waiting, while more recent applicants for travel had passed through in less than a month. It also noted that the amount of people who had been able to exit during the more limited, sporadic openings of Rafah in the past had halved.

The bribes help Palestinians trying to leave Gaza to exit the enclave but do not necessarily change the nature of the crossing.

"They think they'll cross with VIP treatment but they're shocked by the treatment they face, even with the coordination, because they are Palestinian,” said the travel agent. “The treatment they face is like any other citizen, they witness the injustice and the insults.”

Images of the chaos at Rafah are repeated during every opening of the border, people waiting in queues and on buses. Even those who have reached the top of the Hamas-run waiting list are unsure about when exactly they will cross, relying on lists that are unofficially posted on Facebook pages.

Those who pay can skip that, but still have to go through Hamas and then Palestinian Authority waiting halls before entering the Egyptian section, where the fortunate sleep on plastic benches and others on pieces of scrap cardboard while they wait for border officers and intelligence agents to hand out stamped passports, call in interviewees and turn away the unfortunate.

They added people could also be deported back to the country they had travelled from if Rafah was closed - adding that one of the major benefits of the border’s more consistent operation was the end of this practice.

Yet another waiting room awaits in Rafah, for Palestinians who have already passed through Cairo and the Sinai and have almost returned home. They must arrive before 11am but usually cannot exit into Gaza until the night.

“Why must I wait for 12 hours when you only need to stamp my passport and let me enter Palestine? It should take less time, no more than one hour,” said Khalid*, who returned to Gaza in September after going to Egypt for medical treatment, describing how he was told by Egyptian officials that they only process returnees to Gaza once they have dealt with hundreds leaving.

While the longer openings at Rafah have led to an increased number of Palestinians leaving Gaza, it has also encouraged those previously unsure about making the return journey.

There was an instant spike in the number of people leaving Gaza from May, but a more gradual rise in the number of returnees has since overtaken, with more than 7,100 entries into Gaza compared to 6,100 exits in September. In contrast, the numbers leaving Gaza made 77 percent of the traffic through Rafah in May and June.

The travel agent said during one trip returning from a conference abroad, he had planned to arrive in Gaza in time to celebrate the Eid religious festival with his family, even paying an Egyptian official to leave the airport and skip the wait for a collective bus to the border.

But Rafah was closed and he had to spend a month living in a hotel in Cairo. When he did travel to Rafah, he arrived at dawn but had to wait the whole day in the border’s waiting room.

"No water, no food, no services, children ill from the heat, no fans, and the Egyptian police officer is drinking his tea, watching over us," he said.

“Then at night, they started stamping the passports and throwing them in the air,” he says, imitating the officer’s nonchalant tossing action.

“A three-day business trip cost me more than 50 days of suffering and trouble.”

Days in the desert

In times more peaceful, the road across the Sinai Peninsula cuts through a barren, dry landscape that stretches for hours. But conflict in the Sinai, where the Egyptian army has taken on militants allied to the Islamic State group (IS), has elongated that journey by forcing travellers through dozens of military checkpoints.

They can reportedly number up to 36 and take Palestinians through the most dangerous part of the Sinai, where fighting is concentrated in the peninsula’s northeastern corner between Rafah and Arish. All Palestinians stop in Arish, both on their way back to Gaza, when they have to sleep there to wait out the Sinai curfew and on their way towards Cairo. It is the site of the main checkpoint in the region, as well as a frequent target of militant attacks.

Satellite images show how much of the landscape Palestinians from Gaza travel through has been transformed by the insurgency, including during the past year when Egypt launched Operation Sinai 2018 to “clear Egpyt's territory of terrorist elements”.

Where traffic once flowed through northern Sinai towns like Sheikh Zuwayd, between Rafah and Arish, the roads have been cleared of even parked cars and major junctions turned into checkpoints narrowed with earthen berms and stationary armoured vehicles.

Experiences at these checkpoints vary. Ghunaim said they were “treated like animals.”

“You feel that your brothers, the Arabs, are shitter than Israel. Muslims are against us. The biggest side of the siege around Gaza. You feel like you are nothing around the world,” he said.

“Sometimes when the Egyptian army knows that we are Palestinian people they make things easy for us,” says Khalid. “It's something we appreciate.”

The journey’s delays are compounded by the 2013 closure of the al-Salaam bridge over the Suez Canal, forcing everyone to now take a ferry across the waterway to mainland Egypt. Collectively, Palestinians say the time spent stopped at checkpoints and waiting for buses and ferries has turned a bus journey of around seven hours from Rafah to Cairo into one that can take up to four days.

The wait in Cairo

After his four days waiting for buses and ferries and at borders and checkpoints, Ghunaim had only a day to spend in Cairo before leaving from the airport for Tunisia, where he has worked with local artists on his music.

For the Gazan people in Egypt, their lives are really a mess

- Mahmoud, Palestinian

But many have to wait much longer. Some for visas that are troublesome to obtain in a country where they have little status, even when they have invitations to work or study abroad, while others simply try to work out what to do next.

Mahmoud spent three weeks in Cairo after his journey through the Sinai, finding a room in an apartment shared by other Palestinians who had paid the tanseeq. Many of them were struggling to work out what to do next, he said.

“If you really want to leave Gaza, you should leave and know what you're doing. It was really a sad truth,” he said.

“They want a change because the Gaza situation is unchangeable. They just want to leave to see Egypt to try and find new opportunities... some of them go through the Egyptian airport to Europe and seek asylum but most of them are sent back to Gaza because the Cairo airport refuses to let them get on the planes because they don’t have visas.

“For the Gazan people in Egypt, their lives are really a mess.”

*Some names have been changed to protect the identity of the source.

This article is available in French on Middle Easte Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.