From the Algerian hinterland to Unesco: The incredible saga of rai

The scene takes place in Oran, in western Algeria, during a rai festival in 1985. As the end of the evening approaches and the group on stage, Raina Rai, sings its most famous hit, “Zina”, a good part of the public begins to whistle and boo.

Why this sudden hostility? Because the song includes a verse that is unacceptable to parts of the Oran public: “Oh Zina, art and rai were born in Sidi Bel Abbes [a city of western Algeria].”

Rai had emerged from the ghetto to establish itself as the most fashionable musical genre in Algeria before breaking through internationally

By booing Raina Rai, the Oran public was publicly and vocally challenging this version of the origins of rai, at a time when different regions of the country were embroiled in rivalry over the paternity of this style of music. But the dispute was exclusively Algerian, even limited to a part of the country’s west.

Indeed, Morocco was never cited as the land of rai; hence the perplexity over the controversy born a decade ago, and widely relayed on social networks, granting Morocco its paternity.

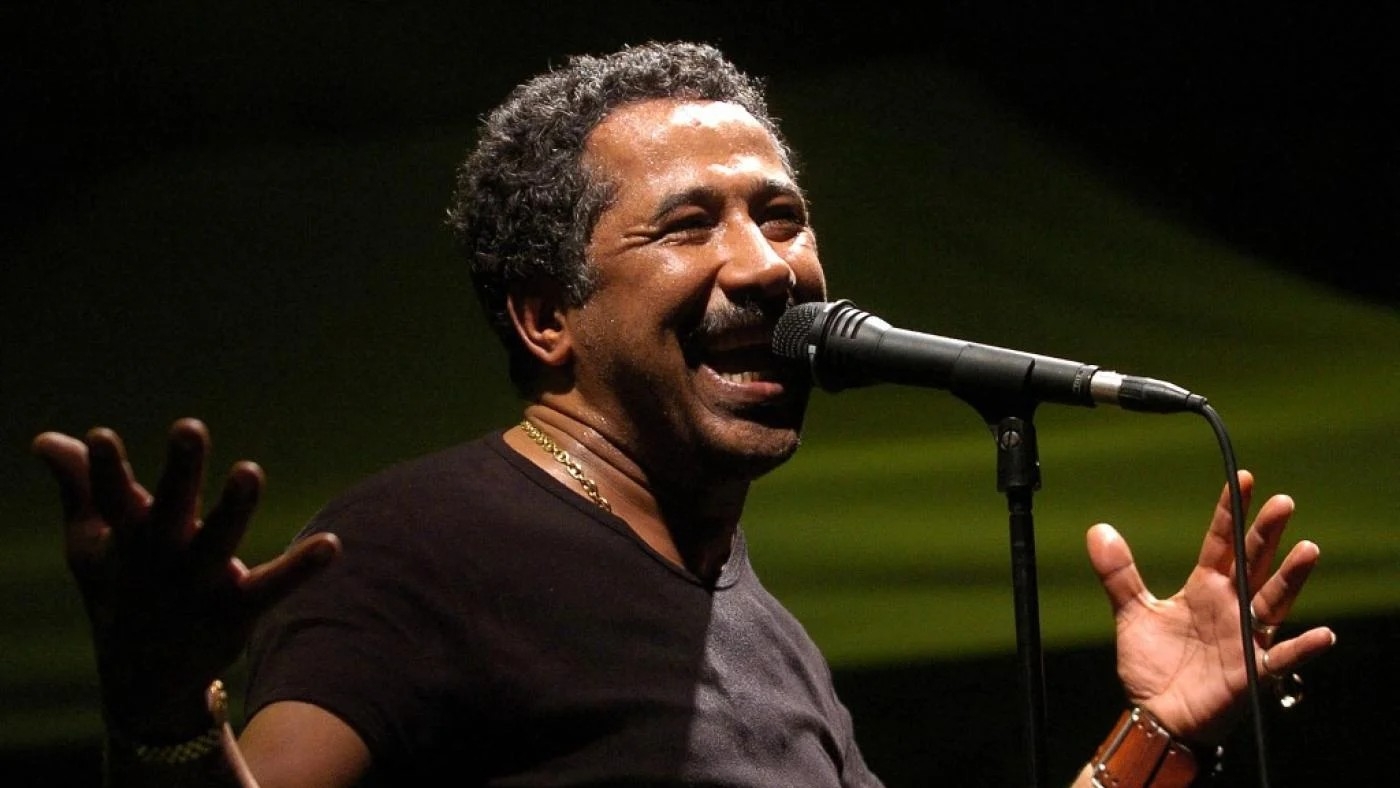

By the end of the 1980s, rai had emerged from the ghetto to establish itself as the most fashionable musical genre in Algeria before breaking through internationally, becoming an artistic but also cultural, economic and political issue. Many claimed paternity amid the fashionable trend of the Cheb (young people) who emerged in the 1980s - such as Khaled, Sahraoui, Hamid and Fadela - a generation that has now largely reached its sixties.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In this rivalry, the advantage was Oran’s, with its renowned underground life, cabarets and financial power. Considered Algeria’s second city, Oran was a major hub where artists, creators and wealthy people converged, attracted by its lively nightlife. It was also the city of the major star, Khaled.

A timely shift

Sidi Bel Abbes, of which Raina Rai was the flagship group, contested the supremacy of Oran, arguing for the precedence of the Zergui Brothers - singers who achieved short-lived fame after trying to introduce new instruments into rai while preserving its traditional tonality.

If Oran was a port city, open to emigration and to the Mediterranean, Sidi Bel Abbes, closer to the rural world in which rai had long existed, was more influenced by the traditional poetry that this musical genre conveyed.

Ain Temouchent - a city even further west than Oran and Sidi Bel Abbes, which saw the emergence of the most famous rai trumpeter, Bellemou Messaoud - also wanted to establish itself as a pioneer of the genre. Bellemou and the Zergui Brothers both played an essential role in the evolution of rai by introducing modern instruments into a genre traditionally based on the flute.

Until the early 1970s, rai was traditional music, intended for a rural audience, and therefore inaccessible to city dwellers and international audiences. This suddenly changed during the second half of the 1970s.

🔴 BREAKING

— UNESCO 🏛️ #Education #Sciences #Culture 🇺🇳 (@UNESCO) December 1, 2022

New inscription on the #IntangibleHeritage List: Raï, popular folk song of #Algeria 🇩🇿.

Congratulations! 👏

ℹ️ https://t.co/n5nd2IfvLJ #LivingHeritage pic.twitter.com/OMVUx3K6Fb

By introducing modern instruments championed by a new generation, rai offered suburban youth a musical genre adapted to their aspirations and ways of life, making it possible to express the state of mind of a conservative society held prisoner by taboos.

Algerian society, which was 80 percent illiterate and rural at independence in 1962, had by then become largely educated and was urbanising at a frantic pace. The post-independence generation had become the majority, and they had a different view of the state, its institutions and political life. But they were excluded from decision-making centres, forced to express their rejection of the established order in a disorderly manner through rai, in stadiums, and also through rampant Islamism.

This shift did not happen without artistic damage. Rai had become a jungle where everyone pirated everyone. The concept of copyright was unknown. It was not until the end of the 1980s, with the international breakthrough of rai, that things began to change.

In addition, most traditional hits are covers of heritage texts, some dating back a century or more, or songs that have fallen into the public domain. Conversely, many modern hits, carried by rhythm and quality composition, suffer from the crude poverty of their lyrics. Very few from the previous generation succeeded in adapting to these changes: Cheikha Rimiti, the immortal “granny of rai”, was the exception that proves the rule.

Promoting the genre

It is thus on this specific terrain - sociological, cultural and political - that rai made its final evolution to being consecrated by Unesco, which registered it on 1 December as part of the world’s “intangible cultural heritage”.

But this short history would be incomplete without mentioning the role of a few people who pressed the right button at the right time to promote rai. Publishers Rachid and Fethi Baba Ahmed, from Tlemcen, played an essential role in this regard; the former was assassinated by armed Islamists in the 1990s, as was crooner Cheb Hasni.

The famous Algerian talent scout Boualem Benhaoua of Disco Maghreb, who French President Emmanuel Macron visited during his last trip to Algeria, also helped many young people to emerge. But the man with the strangest background in this field was Colonel Hocine Senoussi, a trained pilot and veteran of the war of liberation (1954-62), who was appointed in the 1980s as head of the Office Riadh El Feth, an Algerian cultural and commercial complex.

A supporter of an open society and of the country’s youth in a single-party era, Senoussi appeared as a godfather for this musical genre. He offered it a kind of salutary institutional coverage when, it should be remembered, rai was boycotted by public media - considered vulgar and unhealthy, inciting depravity and debauchery.

This escalated to the point of caricature, as evidenced by the fate of Cheba Zahouania. This rai star, who started singing in the 1980s, initially did not appear in public, content to record cassettes amid a reported family dispute. Since then, things have changed a lot and she has become one of the most courted stars, with her videos on YouTube racking up millions of views.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article has been translated and condensed from the MEE French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.