America's exceptionalism will ultimately be its downfall

If what has happened to America during the past 20 years - the "war on terror", the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the 2008 financial crisis, Donald Trump’s election, the Covid-19 pandemic, the assault on the US Capitol and, ultimately, the humiliating exit from Kabul - feels like deja vu, that's because it is.

The fall of Kabul to the Taliban takes the mind back to Saigon and the 1970s, another difficult decade for America.

Back then, as now, the US had been polarised by widespread protests and had been humiliated after the Vietnam war, with America's European and Asian allies puzzled by its behaviour. The US's unilateral decision to remove the dollar from the gold standard hugely disrupted the global financial system.

The decade after the turbulent 1970s saw America preside over the most transformational event of the 20th-century’s second half: the end of the Cold War

The Watergate scandal put an abrupt end to Richard Nixon’s so-called imperial presidency. Two oil shocks, at the beginning and end of the decade - partly attributed to US mishandling of the Yom Kippur War and the Iranian revolution, including the humiliating US hostage crisis - set in motion a global recession and widespread concerns and anxieties about American power.

Yet in the decade following the turbulent 1970s, America reinvented itself, presiding over the single most transformational event of the 20th-century’s second half: the end of the Cold War and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union (only hastened by the USSR's fatal mistake of invading Afghanistan in 1979). America's unipolar era had arrived.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A few years later, radical Islam and 9/11 offered America another challenge. What followed is well known: an era of US hyperpower that may have just symbolically ended in Kabul.

China is now replacing radical Islam as America’s enemy number one; a chilling reminder of another die-hard attitude of western (American) liberal interventionism: its pathological need for an enemy to justify and protect its way of life, identity and hegemony.

Beijing threat

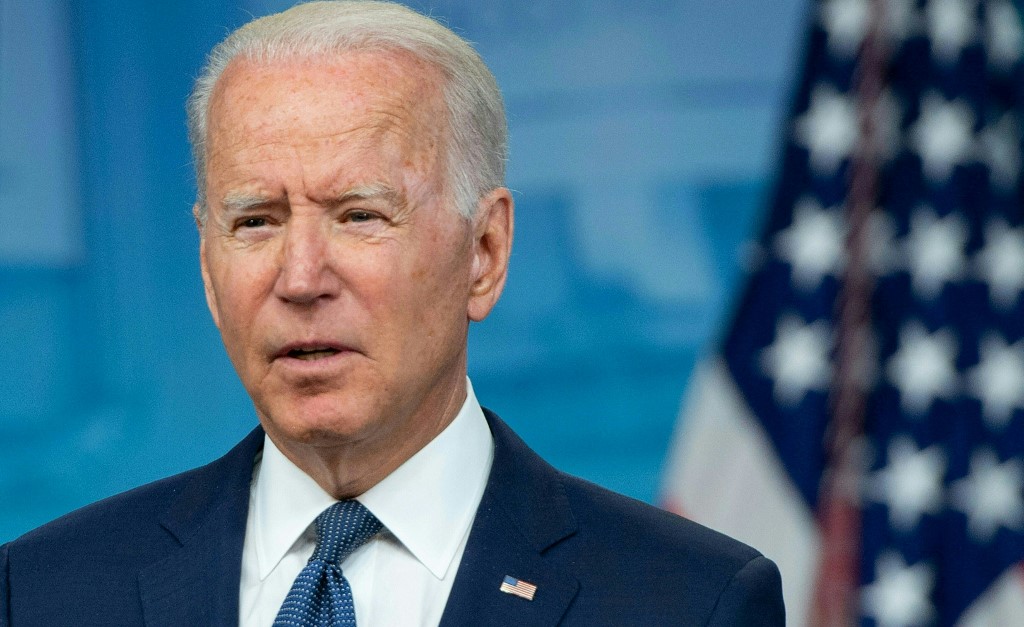

Some thinkers, and the current American president, Joe Biden, are now busily justifying the withdrawal from Afghanistan as a better way to address the more compelling threat represented by Beijing and its refusal to accept a world order based on rules established by America.

In a recent essay, the neoconservative Robert Kagan claimed: “In the real world, the only hope for preserving liberalism at home [in the US] and abroad is the maintenance of a world order conducive to liberalism, and the only power capable of upholding such an order is the United States.”

If such beliefs were only held by arch-neocons like Kagan, it might be fine. But unfortunately, they are also held by the Biden administration, as witnessed by its first Interim National Security Strategic Guidance document.

“When we defend equal rights of all people," it read, "we ensure that those rights are protected for our own children here in America.”

In essence, these are all manifestations of American exceptionalism.

Henry Kissinger explained it as the belief that American principles are "universal and that the governments that do not practise them are not fully legitimised. A notion so much rooted in the American thinking… that it induces [them] to think that a part of the world lives in an unsatisfactory, provisional, situation and that one day it will be redeemed [by America]". The net result is a latent conflict between the US and much of the world.

There is now a growing feeling that the US's unipolar moment is not only ending but has been squandered. Long before Kabul’s fall, many in the international community had been asking if a major new era of world history was upon us and a new world order in the making. And, if so, according to which rules and decided by whom?

Global thinkers

Recently, the Economist invited some global thinkers to address the topic of American power.

Francis Fukuyama emphasised that America “overestimated the effectiveness of military power to bring about fundamental political change, even as it underestimated the impact of its free-market economic model on global finance”. While he correctly pointed to mistaken calculations, he ignored the core roots which may have driven them.

Niall Ferguson framed America’s demise with the British imperial experience, but he succeeded only in asserting banalities, such as that “the retreat from global dominance is rarely a peaceful process” and in blaming Barack Obama’s renunciation of global policing as the trigger for Russian intervention in both Ukraine and Syria.

If American power is to be defined by its relationship with China over the next decades, it is essential that the US avoids repeating its historical mistakes

Henry Kissinger explained what went wrong in Afghanistan by emphasising only America's “inability to define attainable goals and to link them in a way that is sustainable by the American political process”.

Robert Kaplan asserted that, in the era of climate change and of the fourth industrial revolution, where conflicts revolve around big data, artificial intelligence, 5G, cyberwar and quantum computing, geography still matters, and it still helps the US.

Hardly any of them addressed the big elephant in the room where US power is concerned: American exceptionalism. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this was mentioned by one of the few non-western thinkers the Economist consulted - the Indian novelist Arundhati Roy.

If American power is to be defined by its relationship with China over the next decades, as Peter Beinart warned recently, it is essential that the US should avoid repeating its historical mistakes.

Hard and soft power

American power has always involved a fine-tuned combination of hard and soft power which, through deterrence and inspiration, paved the way to Cold War victory.

Over the last four decades, China has been very smart in its use of soft power, such as through its massive Belt and Road Initiative. Washington has not only lost its skills in blending hard and soft power, but it has also been too keen on using the hard one. When it did opt for soft power, it used sanctions buttressed by the weaponisation of the dollar and the US Treasury’s financial blacklisting of foes and friends alike.

As Obama once said of the US: "Just because we have the best hammer, does not mean that every problem is a nail."

Rebuilding America’s power means rebuilding its soft power, with less emphasis on relentlessly emphasising the US as the only country which can guarantee peace, freedom, economic growth and prosperity. Pretending to sustain a rules-based world order only on a binary choice - either you are with us, or you are against us - is not the best recruiting tool.

Quite useful also would be the dropping of the conviction that any country questioning the liberal and globalised world order is evil and immoral, an example of fanaticism typical of a retrograde civilisation and, above all, that such questioning always constitutes a threat to the security of the United States.

Most importantly, restoring American credibility requires the abandonment of the frequently practised hubristic belief that the rules of such a world order apply to all nations but the US.

Arnold Toynbee said that the encounter between the West and the world has been modern history’s capital event.

Now, after five centuries of western dominance, marked by the Renaissance, the great geographical discoveries, the Enlightenment, the political, industrial and scientific revolutions and, since 1917, progressively led by the United States, the world as we have always known it might become more complex and multipolar.

The rise of Eurasia, climate change, pandemics and the fourth industrial revolution mean that the West might not occupy centre stage in the future. The 21st century is seeing a tectonic historical shift.

Instead of framing it as an epic clash between democracy and authoritarianism, for the sole purpose of maintaining its more and more unsustainable hegemony, America would do better to manage this process constructively and pragmatically.

To make a start, it must drop its flaunted exceptionalism.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.