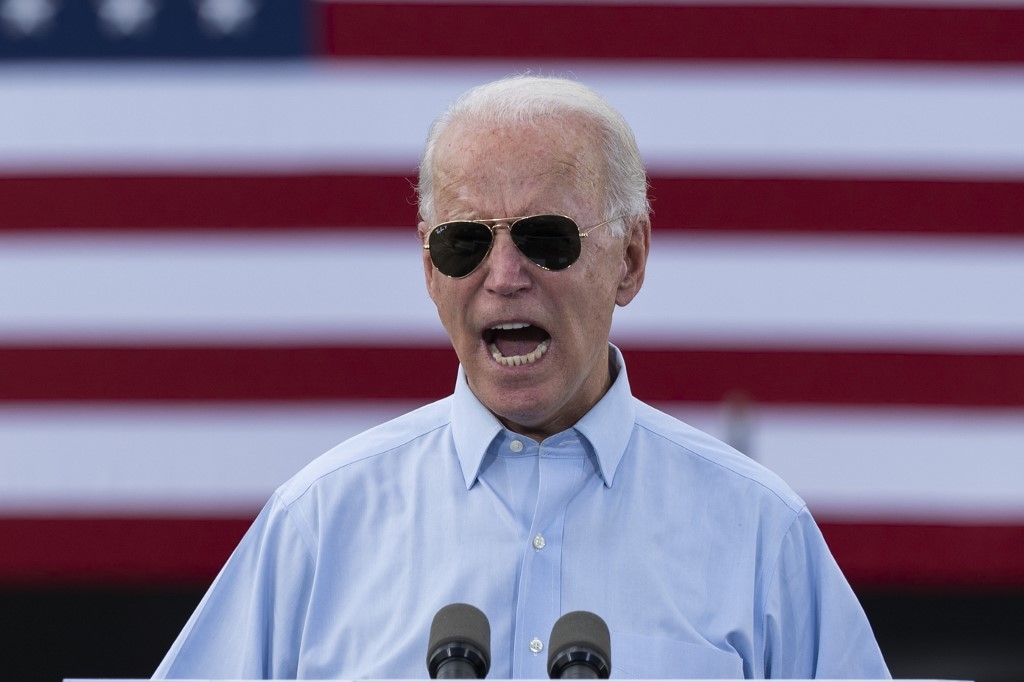

Can Joe Biden avoid creating a Trump on steroids in 2024?

This week, Americans will choose their next president. The winner may not be declared even hours after the polls close. Although analysts are predicting that a blue wave will sweep Democrat Joe Biden to power, what happened to then-frontrunner Hillary Clinton in 2016 should engender caution.

In addition, President Donald Trump has already indicated that he may challenge a defeat, and the winner could be decided by a Supreme Court that he successfully reshaped. Former president George W Bush already trod that path against his opponent, Al Gore, in 2000.

Let's assume that the worst - battles in court and on the streets - does not happen. Let's try, instead, to imagine how the country's standing in the world should change under a Biden administration.

Four years in denial

Relief will ripple around the world after the rollercoaster we have all endured over the last four years. But are we really so sure that the root causes that put a man like Trump into the White House in the first place have been addressed, and that in four years' time a man even more toxic than Trump - such as Senator Tom Cotton - would not step up to challenge a moribund Democrat president?

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The blue wave turfing Trump out of the Oval Office would be pointless if Biden and his advisers believe, to quote the recent encyclical by Pope Francis, "that the only lesson to be learned was the need to improve what we were already doing, or to refine existing systems and regulations". If so, a Biden administration would be part of the Trump problem, and would spend four years in denial.

A president who listens rather than tweets will be better placed to win hearts and minds, and to confront the challenges - whether real or imaginary - presented by rival powers

While a change of approach is crucial for domestic US politics, it is also needed in foreign policy. A paradigm shift is required.

Sure, Biden might already have in his back pocket better policies on global issues. He will re-engage the US in common fights to deal with existential threats: climate change, pandemics, trade and tech wars. He will lead a concerted effort to kick-start a global recovery after the Covid-19 pandemic. Reinforced multilateralism will be necessary to achieve such goals.

He could repair the transatlantic rift, not only within Nato, but with the EU as well; he could recommit the US to the World Health Organization, the Paris climate agreement and the Iran nuclear deal, and he may have a more nuanced and detached view of the Abraham Accords.

Abandoning exceptionalism

A president who listens rather than tweets will be better placed to win hearts and minds, and to confront the challenges - whether real or imaginary - presented by rival powers and trends, including China, Russia, Iran, Turkey and Islamic fundamentalism.

But nothing meaningful will be achieved if the US does not abandon its obsession with being a global leader; its belief in its own exceptionalism. Although Biden believes that the US must lead again, he may soon be forced to confront the reality that those days have gone forever.

Of course, the country will continue to provide a crucial contribution towards shaping a new, fairer and less hubristic multilateral world order. But the US in 2021 will be quite different from the self-proclaimed victor of the Cold War in 1991. What was true at the time will not necessarily be true again.

The biggest mistake a Biden administration could make would be to continue Trump's ineffective and dangerous policy against China, the obsession with Russian interference in the US political system, or the ludicrous notion that Iran possesses such capabilities.

Sinophobia, Russophobia and Islamophobia are useful tools for demagogues and lunatic populists, but they are of as much use as a chainsaw to a dentist. They hold no value for a US elite committed to reshaping a fairer and more effective global order.

Serial mistakes

As authoritatively admitted by a former insider, the things dividing western societies were not created by Russia. Do Biden and his team really believe in Russiagate, as Bush believed propaganda about Iraq's weapons of mass destruction? Do Biden and his team really believe the rise of China has resulted only from unfair trade practices and intellectual property theft by Beijing, as Trump posits - or that the main problem we face is "the aggressive state capitalism of modern autocracies"?

A large part of the China and Russia "challenges" resulted from strategic US mistakes since the end of the Cold War - far before Trump nurtured any presidential ambitions. The Iranian and Turkish ones are the consequences of serial mistakes carried out in the Middle East. These are outcomes for which the Clinton, Bush and Obama administrations hold the lion's share of the blame.

The US should stop looking for excuses abroad for its own serial mistakes, both internal and external. As noted in a recent Foreign Affairs essay, the US should stop basing its foreign policy on the systemic search for "monsters to destroy" around the world. Above all, it should stop creating its own enemies to feed the military-industrial-media-congressional complex.

Biden should abandon the notion that new global players such as China, and old ones such as Russia, will accept a new US leadership, regardless of the premises upon which it is built. On the contrary, it seems that a point of no return has been reached as far as Russia is concerned, and a similar situation is approaching for China.

As for Iran, restoring the nuclear deal - as Biden has hinted he would - would help, but there is a question of sequencing. It was the US who walked away from the international agreement, not Iran.

New international order

A new international order will not be the liberal one we have known under US leadership for decades, with its heavy baggage of weaponising the dollar, indiscriminately sanctioning dozens of countries, waging a global war on terror with no legal restrictions, and too frequently resorting to the use of force.

The US and its allies, whether they like it or not, should adapt to a world where they cannot call all the shots, and where their narrative of events is constantly challenged.

Regeneration depends on the acknowledgement that there are fundamental problems with the way the US wields power

The four years of Trump were not a temporary blip. The West is collapsing, and with it, some of the most powerful and dominant institutions in Washington, where a moral convulsion is taking place. Regeneration depends on the acknowledgement that there are fundamental problems with the way the US wields power.

Democracy faces bigger threats than Russia or China. If liberty is conceived, as it has been in the US for the last three decades, as small government without excessive taxes on the rich, and if this neoliberal order has grown far more powerful than democracy, we will have a populist revolt of the sort we have been witnessing all over the western world. Add the consequences of Wall Street's financial recklessness to this mix, and we have the best answer to what went wrong in the last few decades.

While the US political establishment that identifies with the Republican Party is and will remain beyond redemption, Biden should grab the opportunity of a victory to distance the country from previous policies, both domestic and foreign. Democrats failed to do this in 2008 and 2016. Repeating this mistake in the years ahead would be unforgivable.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.