Collapse of the Middle East order is under way. The future is up for grabs

The political order of the Middle East is in the process of collapse. For those struggling for a future of dignity and democracy across the region, there’s no hope of reform of the existing system of power. That is the verdict of two activists, Iyad el-Baghdadi and Ahmed Gatnash, in their new book The Middle East Crisis Factory.

However, this is not a statement of despair, but one of defiance from the generation of the 2011 uprisings. “There is no hope that the collapse can be stopped," they write. "We gave up all hope in that order long ago. We have to place our hope beyond that order. It’s collapsing anyway - let it come crashing down so we can have a shot at a life of liberty.”

The writer-activists see the battle for human rights and democracy across the Middle East since 2011 as moving beyond traditional nationalism, anti-imperialism and Islamism

Part history, part human rights manifesto and part advice manual for western governments, the book describes how a history of western intervention, cynical alliances with dictatorships, and the failure of post-colonial governments has led to this point.

Baghdadi is a Palestinian entrepreneur and human rights activist who grew up in the United Arab Emirates and is now a political refugee in Norway. Gatnash is a Libyan political exile based in London.

Baghdadi is a former associate of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, who was murdered in 2018 in Istanbul by a team of Saudi government agents. He is himself now under Norwegian police protection after coming under threat from the long arm of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s death squads.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Brutal transition

The authors see the current point of transition from post-colonial regimes to an order that might offer hope to millions denied a future as one akin to Europe’s bloody transition to modernity a century ago. Europe had to undergo two devastating world wars and genocides that left more than 60 million dead before a semblance of stability and prosperity arrived.

The authors envisage a transition in the region that will likewise take decades, and will not be smooth, having already in the past 40 years seen wars, invasions and genocides that have killed millions and seen millions flee as refugees.

The titular 'crisis factory' is the triangle of post-colonial authoritarianism, western support for tyrants and military intervention, and extremism

The titular “crisis factory” is the triangle of post-colonial authoritarianism, western support for tyrants and military intervention, and extremism. Each of these forces and structures feeds into each other in a destructive cycle that inhibits and prevents the emergence of civic and democratic governance across the region.

The writer-activists see the battle for human rights and democracy across the Middle East since 2011 as moving beyond traditional nationalism, anti-imperialism and Islamism.

The Syrian uprising, and the Assad regime's response to it, is a prime case of a symbiotic relationship between authoritarianism and terrorism, the authors argue. The regime ruthlessly suppressed peaceful protests while freeing Islamist militants deployed against US forces in Iraq to operate within Syrian territory at the outset of the uprising in 2011. Much has been written about this undeclared co-dependency, yet the complicity between regional governments that enabled and armed these hardline groups, including Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey, is neglected, echoing a common narrative in western reporting of the war.

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s brutal rise to power in Egypt also coincided with the increased activity of militant groups in the Sinai peninsula, marking another example of the “crisis factory” and the way tyrants need the threat of terrorism to reinforce their shaky legitimacy.

Regimes that invite intervention

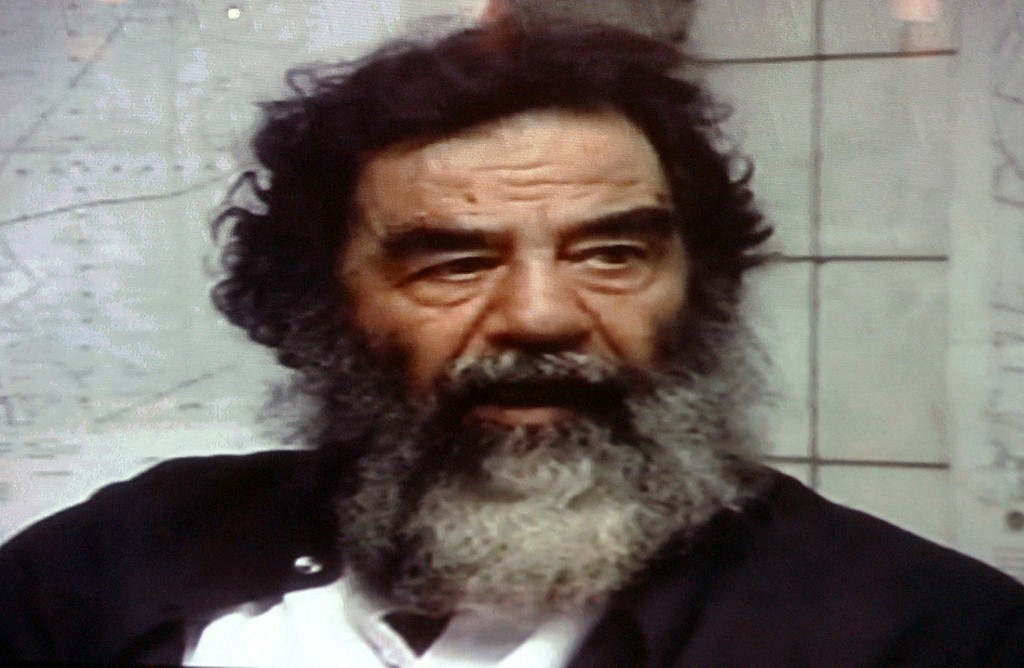

The Baathist regimes in Iraq and Syria are examples of dictatorships that saw themselves as anti-imperialist and yet, the authors point out, through their actions and industrial-scale abuses, ultimately exposed their countries to intervention and foreign occupation.

Such regimes have given western powers justification for war and intervention, leaving the region in ruins and chaos, as occurred following Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, leading to the US-led war of 1991, and the later invasion led by president George W Bush in 2003. Of course, the latter’s justification for invading Iraq was non-existent weapons of mass destruction.

The thesis that there is a symbiosis between the forces of tyranny, western neocolonialism and extremism is bold and arresting. The question arises as to whether the authors are deploying it fairly in all cases.

In the case of Saddam, the authors argue that the dictator’s continued defiance of western powers, following the imposition of devastating sanctions after his invasion of Kuwait, was reckless and ultimately led to the next war. They point out that Saddam was offered an opportunity to step down and leave Iraq by the UAE’s Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan al-Nahyan, but refused. But this proposal, on the eve of the US invasion in 2003, was not a realistic one that Saddam would have embraced. As the book states, it took US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld a matter of hours after the 9/11 attack to propose an invasion of Iraq, which had nothing to do with the al-Qaeda operation.

In the wake of the 2011 uprisings, western liberal rhetoric is contrasted with the cynical realpolitik that prioritised stability over human rights.

The authors berate the US administration of Barack Obama for signing a nuclear agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran that sidelined its abuse of human rights, while allowing Iran to continue its interference across the region, from Syria to Yemen. This argument is remarkably close to the one used by Donald Trump when he unilaterally withdrew from the agreement in 2018.

Alternatives to intervention

The authors rightly oppose the history of military intervention in the region and also the blanket use of economic sanctions that cause immense suffering, while failing to dislodge regimes such as Iran’s or Syria’s.

A more effective approach, they argue, is smart sanctions targeting individual leaders’ assets, which are less hurtful to the people being oppressed, such as the Magnitsky Act – used against Russia’s Vladimir Putin and his cronies.

The other important tool available both to human rights activists and legal groups is universal jurisdiction legislation, which has been used to bring individual officials of the Assad regime to court in countries such as Germany and Spain.

Baghdadi, an Emirati Palestinian, places the Middle East conflict within the same triangulated framework, arguing that Israeli colonialism has been aided to some extent by the choices of Palestinian leaders, including Yasser Arafat and Hamas, in favour of armed attacks and terrorism. They draw a direct parallel between the way US intervention in Iraq “feeds terrorism” and “how Palestinian violence served to justify Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian Territories”.

This critique seems deeply flawed and echoes those of liberal Zionism, comparing armed resistance to the violence of the Israeli occupation and its refusal of all genuine attempts to find a peaceful end to the conflict.

Violence breeds violence, but we must at least identify where the violence begins. This is not simply a loop, it has a structural cause, which is settler colonialism and imperialism, which then leads to resistance.

Violence breeds violence, but we must at least identify where the violence begins. It has a structural cause, which is settler colonialism and imperialism

In the case of Hamas, following the wave of attacks against Israeli civilians in the Second Intifada, it has changed strategy, favouring electoral and popular mobilisation, and also seeking diplomatic options to end the conflict, all of which have been shut down by Israel and its western allies. In the case of the Great March of Return in 2018, as in multiple Israeli attacks on Gaza since 2008, it was met with Israeli snipers and air strikes.

The authors barely acknowledge this evolution, although they do identify Benjamin Netanyahu’s long record of weaponising terrorism against all forms of peaceful activism, in a similar fashion to regimes across the region.

The authors bring their personal knowledge of the uprisings of 2011 to their commitment to a new pan-regional politics that moves beyond the Arab nationalism of old, and the later surge of political Islam and jihadi terrorism. They embrace a heterodox non-violent and non-sectarian politics of human rights, and reject the racist idea that Arabs, Iranians, Kurds or Imazighen are not ready for democracy.

Counter-revolution

The counter-revolution opposing this is led by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Abu Dhabi’s Mohammed bin Zayed and its allies such as Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. The Iranian-led axis is also implacably hostile to this project.

Activists across the region have faced not only the threats of these entrenched forces, and that of terrorism, but also the “ensconced racist western attitudes about who we were as a people, and what we deserve to have, or even aim for, in terms of governance, dignity and human rights”.

Middle East Crisis Factory offers many insights, one being that colonialism and occupation do not always come from outside but can also be imposed from within, when a dictatorship treats its own population, or that of its neighbours, as the colonial other to be caged and repressed, in a continuation of earlier colonial regimes.

Baghdadi is associated with the Oslo Freedom Forum, founded by wealthy Venezuelan-Norwegian Thor Halvorssen, and funded by Google billionaire Sergey Brin and PayPal founder and conservative libertarian Peter Thiel.

This may offer a clue to the book’s partial infusion with western think tank narratives on the region’s politics.

As part of a new generation of activists that will not easily surrender the agency it discovered in the 2011 uprising, they should also guard against that agency being co-opted by the billionaire class.

The Middle East Crisis Factory by Iyad el-Baghdadi and Ahmed Gatnash is published by Hurst on 8 April for £14.99.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.