Despite challenges, Turkey’s Syria policy remains unchanged

The Arab Spring started out as an indigenous process, driven by domestic demands, aspirations and forces. The motto of the protesters - bread, dignity and freedom - was a testament to the domestic-driven nature of the Arab Spring. And yet the way the Arab Spring has evolved has largely been decided by regional and international powers. Nowhere has this has been as clear as in the context of the Syrian imbroglio.

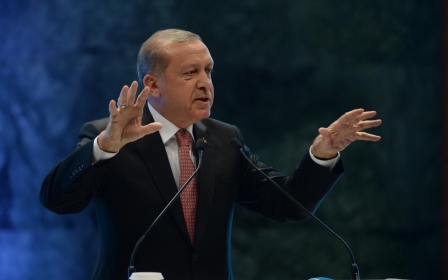

All the major players have made themselves heard on Syria. In most analysis of Syria, we take into account the positions and demands of all regional and international powers with the exception of the Syrian people. The more the Syrian conflict sucks in third parties, the more we pay attention to their activities and statements instead of realities on the ground for a very simple reason: a significant level of realities on the ground are being decided by the activities of regional and international powers. This is well-reflected in the media buzz surrounding Russia’s military build-up and in Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's recent statements on the Syrian crisis, which have since been corrected.

Speaking to journalists in Istanbul, after his trip to Russia to attend the opening ceremony of Moscow's Grand Mosque, and in the company of Russian President Vladimir Putin, Erdogan said: “We can have a process without Assad, or something like going with Assad during a transition period.” This remark immediately caught the attention of Turkish and international media, with analysts and pundits rushing to the conclusion that this remark was a harbinger of change in Turkey's purportedly "failed" Syria policy. The fact that it came after President Erdogan met President Putin, and in light of Russia's major military build-up in Syria, it appeared to give plausibility to this argument.

Yet it didn't take long for observers to realise that this was a hasty and immature judgement, as Erdogan soon rectified his words. He denied any change of heart in Ankara, insisting that Turkey did not see any future role for Assad in Syria, even a transitional one, and that no change had occurred in this regard.

Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu was also unequivocal in his position on Assad and reiterated Turkey's position that there could be no place for Assad in Syria’s future.

During his recent visit to Brussels, and speaking on the issue of the refugee crisis, Erdogan mirrored Davutoglu’s remarks. To thoroughly tackle the refugee crisis, he said, the fulfilment of the following three criteria was vital: to enlarge the train-and-equip programme for the legitimate Syrian opposition; to create a safe zone for people fleeing from the regime of Bashar al-Assad; and to declare a no-fly zone. All these public statements, coupled with those of senior policymakers in Ankara, clearly reflect that there is no change in Turkey's stance on the Syrian crisis.

Ultimately, Turkey still has the same priorities in Syria. Namely, it wants a Syria without Assad that keeps the unitary structure of the Syrian state (meaning that no separate administrative arrangements should emerge - particularly for the Democratic Union Party (PYD) dominated Kurds in the north, until the dust of the Syrian crisis settles - and which exists without any zones of influence dominated by regional and international powers.

Challenges facing Turkey’s policy

Turkey's preference and the current Syrian reality, however, are far from being in accordance. Despite all the atrocities that the Assad regime has committed and all the red lines that it has transgressed, Assad has managed to hold onto power, though in a reduced Syria, thanks to aid of all forms provided by Iran, Russia, Hezbollah, and Iraq.

Syria is unfortunately already divided into four sphere of influence and authority. The power and sovereignty that is normally ascribed to a legitimate state is being shared by four primary forces: the Assad regime, ISIS, the moderate Syrian opposition, and the Kurds, with other groups and factions contesting to establish their own spheres of sovereignty. The more protracted this crisis becomes, the further the fragmentation of Syria becomes a real possibility, if not reality itself.

Moreover, the barbarity of ISIS was used as a smokescreen to conceal the genocidal face of the Assad regime. Assad is farcically suggested to be a partner in combating radicalism, which is a sure recipe for disaster and further radicalisation.

Putin’s suggestion that in order to fight radicalism the Syrian state’s authority and sovereignty needs to be restored misses the point as to why the Syrian state was crumbling in the first place. It was the suffocating authoritarianism, illegitimacy, ineffectiveness, and oppressive nature of the Syrian state that led its people to rebel against it in the first instance. There is no change in this respect.

In fact, on top of this now lies hundreds of thousands of deaths as a result of the regime’s almost genocidal campaign against its own people. In this regard, propping up the Syrian “state” in its current form means restoring a crumbling Iron Fist regime, which will need an incessant supply of manpower and the means to commit further violence in order to make up for its lack of legitimacy.

On top of this, Turkey sees the determination of the pro-Assad camp in keeping the president, but moreover the regime and the interests it represents, in power. The danger of transforming the Baathist regime to form the backbone of the post-Assad state structure is very real.

In contrast, the nominally pro-opposition camp - in other words the US-led West and regional powers such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar - is yet to come up with a well-defined position on Syria, much less a plan to put the necessary means and commitments behind their position. This reduces Turkey's options and makes a significant chunk of its strategies and options contingent upon the positions and activities of others. This in turn always keeps the door of an undesired recalibration of foreign policy towards the Syrian crisis a real possibility, no matter how unpalatable this might be.

Lastly, Russia's military build-up and its military presence on the ground reduces the possibility of the creation of Turkey’s much desired no-fly zone or safe haven, though the necessity for both have not diminished. Turkey's options vis-a-vis Russia are limited. As a growing economy with an acute need for different sources of energy, Turkey currently relies on a prickly Russia and Iran for its energy. This puts Turkey's energy security at risk and significantly reduces its room for manoeuvre vis-a-vis Russia in Syria.

Erdogan's remarks on his way back from Moscow were more of a reflection of him thinking out loud rather than a consequence of a well-conceived and pre-planned strategy. Hence Turkey’s Syria policy remains unchanged for the time being, despite facing increasing challenges. Ultimately, whether these challenges will force the government to overhaul its policy will be contingent upon the results of Turkey’s November 1 snap election.

- Galip Dalay works as a research director at al-Sharq Forum and senior associate fellow on Turkey and Kurdish Affairs at Al Jazeera Centre for Studies.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Syrian woman reacts after her home were damaged by the Russian air strikes in Maasaran town, Idlib, Syria on October 07, 2015. (AA)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.