Saudi Arabia's bot army flourishes as Twitter fails to tame the beast

One of the Middle East’s oldest and most prolific disinformation networks is still going strong on Twitter - and no one seems to know why.

The so-called Diavolo network, which mostly promotes content related to the conservative satellite news station Saudi 24 and its sister channels, has been responsible for spreading sectarian hate speech, antisemitism and conspiracy theories about the murdered journalist Jamal Khashoggi, among other things.

Highly coordinated effort

You only need to search Twitter for a hashtag relating to a country in the Middle East to find one of these bot accounts. They typically copy-and-paste the same content, and feature a video clip with the distinctive Saudi 24 logo in the bottom right corner.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The associated profiles are designed to look relatively plausible, with profile pictures often featuring real people. Although the exact numbers are hard to deduce, my analysis suggests that the network likely consists of up to 3,700 automated or semi-automated accounts.

Two samples were used for this study. Both were generated by downloading around 20,000 tweets containing the phrase ‘محلل قناة"24" (Saudi 24 Analyst) - which is a commonly used phrase by the bot network.

Similarities in account creation date, the platform used by the account, number of followers and similarities in the content shared by the accounts all factor into determining whether or not the account can be flagged as suspicious. The actual size of the bot network is likely bigger, but this sampling method yields the data with the fewest false positives.

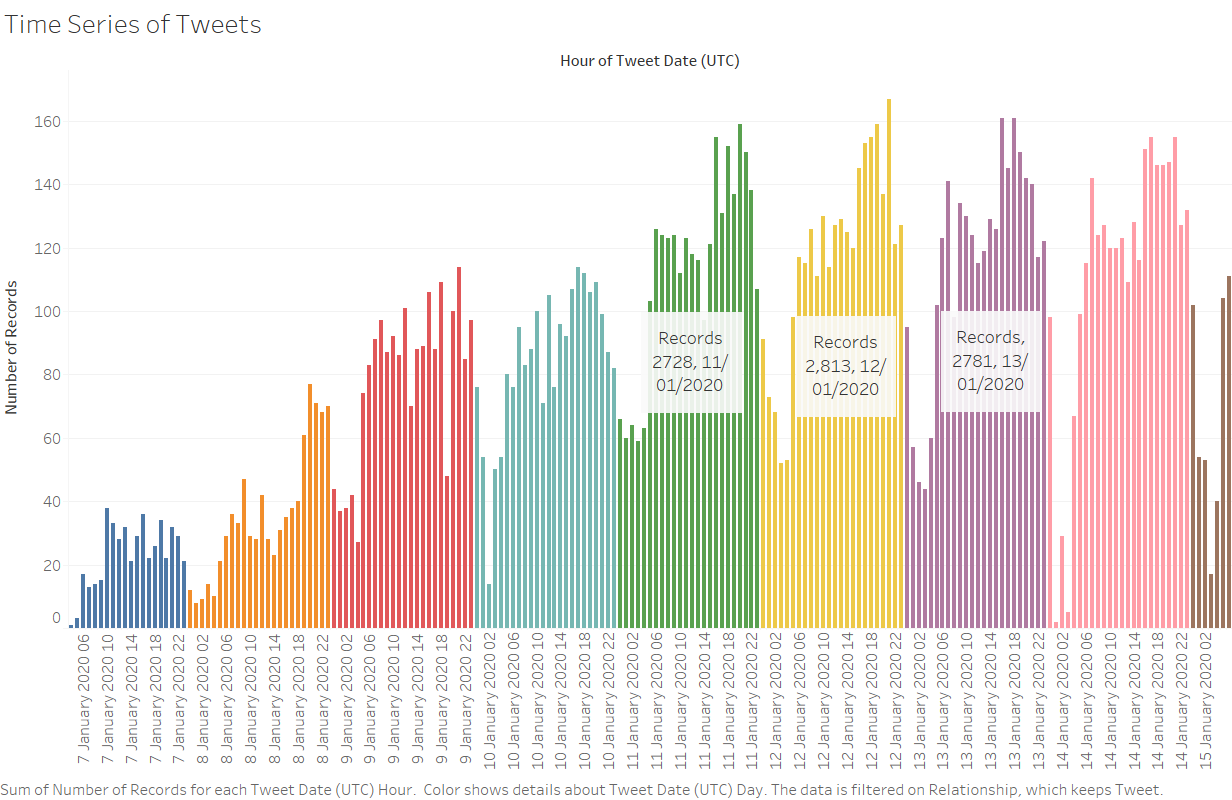

The network itself is constantly active, producing upwards of 2,500 tweets a day

An analysis of accounts, based on commonly repeated words among the network, suggests a highly coordinated effort.

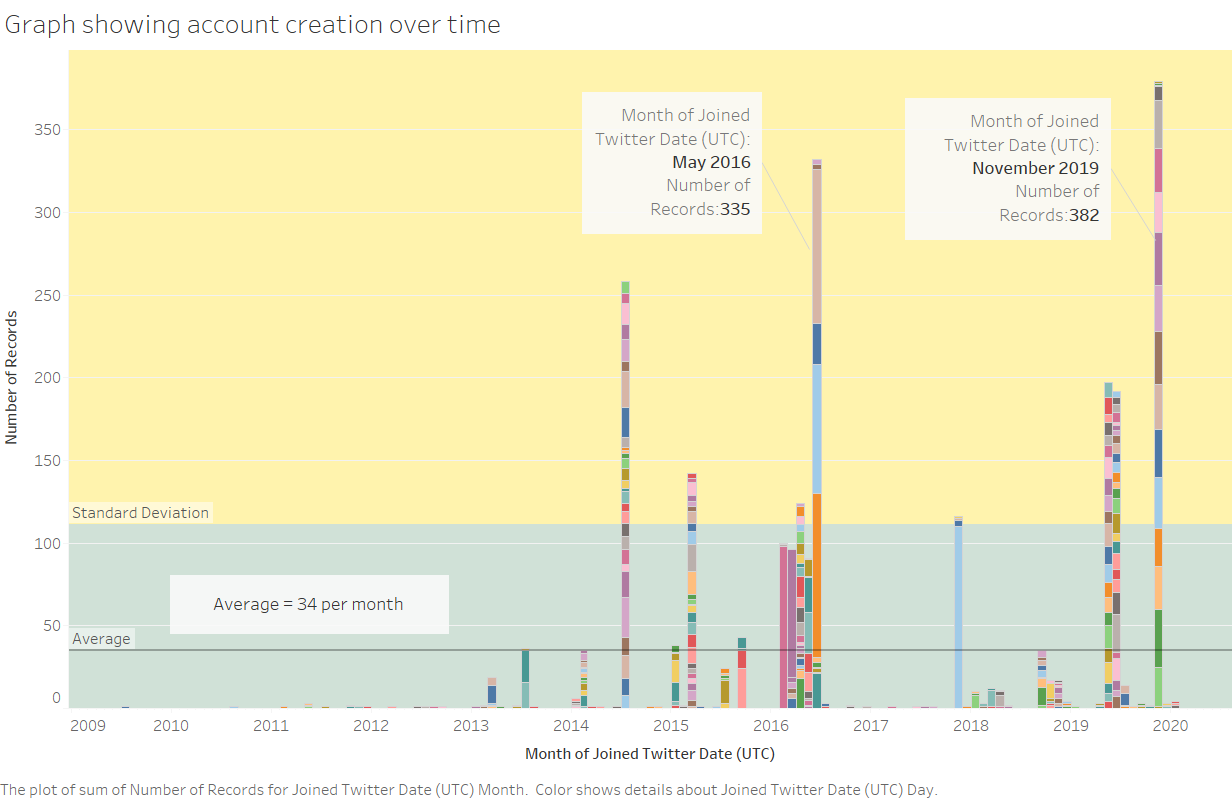

On average, 34 new Twitter accounts have been created each month since 2009, but on occasion, there has been a surge. In May 2016, a total of 335 accounts were created and last November 382 were established. If these accounts were organic, one would expect a more even distribution of creation dates.

While some bot networks are only active sporadically, the network itself is constantly active, producing upwards of 2,500 tweets a day.

Trending topics

In terms of topics, the network consistently focuses on issues related to Iran, Turkey and Qatar. According to my analysis, around a third of all tweets in the past week have contained the hashtag #Iran, while #Turkey, #Qatar and #Saudi each came in at around 17 percent.

Back in 2016, the Saudi 24 network was engaged in spreading anti-Shia hate speech in Arabic. This is perhaps no surprise, given that one of its connected entities was the Safavid Plan, a channel devoted to promoting anti-Iranian news and conspiracy theories. After receiving complaints, Twitter suspended 1,800 accounts, but the network then was much larger and this did little to disrupt its activity. At the time, I estimated the network to involve tens of thousands of accounts.

Although the network has endured several culls since then, it is still going strong, spreading pro-Saudi propaganda and disinformation.

The network also jumps on trending topics, especially when it seeks to defend Saudi Arabia from criticism.

In 2018, the network was highly active in spreading now-debunked conspiracy theories about Turkish involvement in the Khashoggi murder. On the anniversary of the crime last October, the network spammed the #JamalKhashoggi hashtag with videos promoting Saudi businesses, at a time when the Aramco IPO was making headlines.

And after a Saudi recruit shot and killed three US military personnel in Florida, the Saudi 24 bot network spammed the #floridashooting hashtag with messages of Saudi support for combating terrorism.

The network is mostly for broadcasting, and accounts tend not to interact with each other. It was identified by myself and researcher Bill Marczak in 2016 after we followed a trail of metadata breadcrumbs.

Diavolo, meaning “devil” in Italian, was the name of a software programme used to automate tweets through the application TweetDeck.

Twitter's blind spot

Given Twitter’s highly publicised culls of Arabic Twitter accounts spreading “political spam” from both the UAE and Saudi Arabia, it seems incredible that this network remains active.

It is hard to quantify the network’s impact, but videos shared on Twitter frequently get thousands of views. Nonetheless, it’s almost certainly guilty of platform manipulation, which Twitter defines as “the use of Twitter to mislead others and/or disrupt their experience by engaging in bulk, aggressive, or deceptive activity” that could include spam, malicious use of bots or fake accounts.

Platform manipulation is likely to remain a tacitly accepted form of control in the Middle East

The continued existence of the network raises questions about Twitter’s apparent blind spot with regards to the Saudi-connected weaponisation of Twitter. Saudi moles who infiltrated Twitter were recently charged by the US government over spying for Riyadh.

Yet, even after Twitter learned of the breach, CEO Jack Dorsey met Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Twitter has also not adequately explained why it hid the archives of Saud al-Qahtani, a former royal adviser whose account was suspended for platform manipulation.

Despite Twitter’s recent culls, without proper account verification and transparency around the specific relationships the tech company has with particular countries, and the conditions those countries place on allowing Twitter to operate, platform manipulation is likely to remain a tacitly accepted form of control in the Middle East.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.