Why Egypt's civilian opposition is to blame for seven decades of one-man rule

Egypt’s military first seized power in 1952 and again in 2013. Unlike coups that have taken place in other parts of the world, such as Latin America, in both the 1952 and 2013 coups in Egypt, there was a one-man rule backed by the army.

The politicisation of the military during these key years has had significant implications, not least the manner in which the president governs in relation to the military establishment.

For the past 70 years, every Egyptian president has been a member of the military, with one exception of course, the late President Mohamed Morsi, who was elected in 2012 and overthrown a year later. The aspiration of these military presidents helped pave the way for a mode of governance that enshrined personal rule.

These individuals were always protected by their constituency, namely the military, which itself was reliant on support from foreign powers, due to the functional role the regime played in the Middle East at the behest of these foreign interests.

A new political order

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

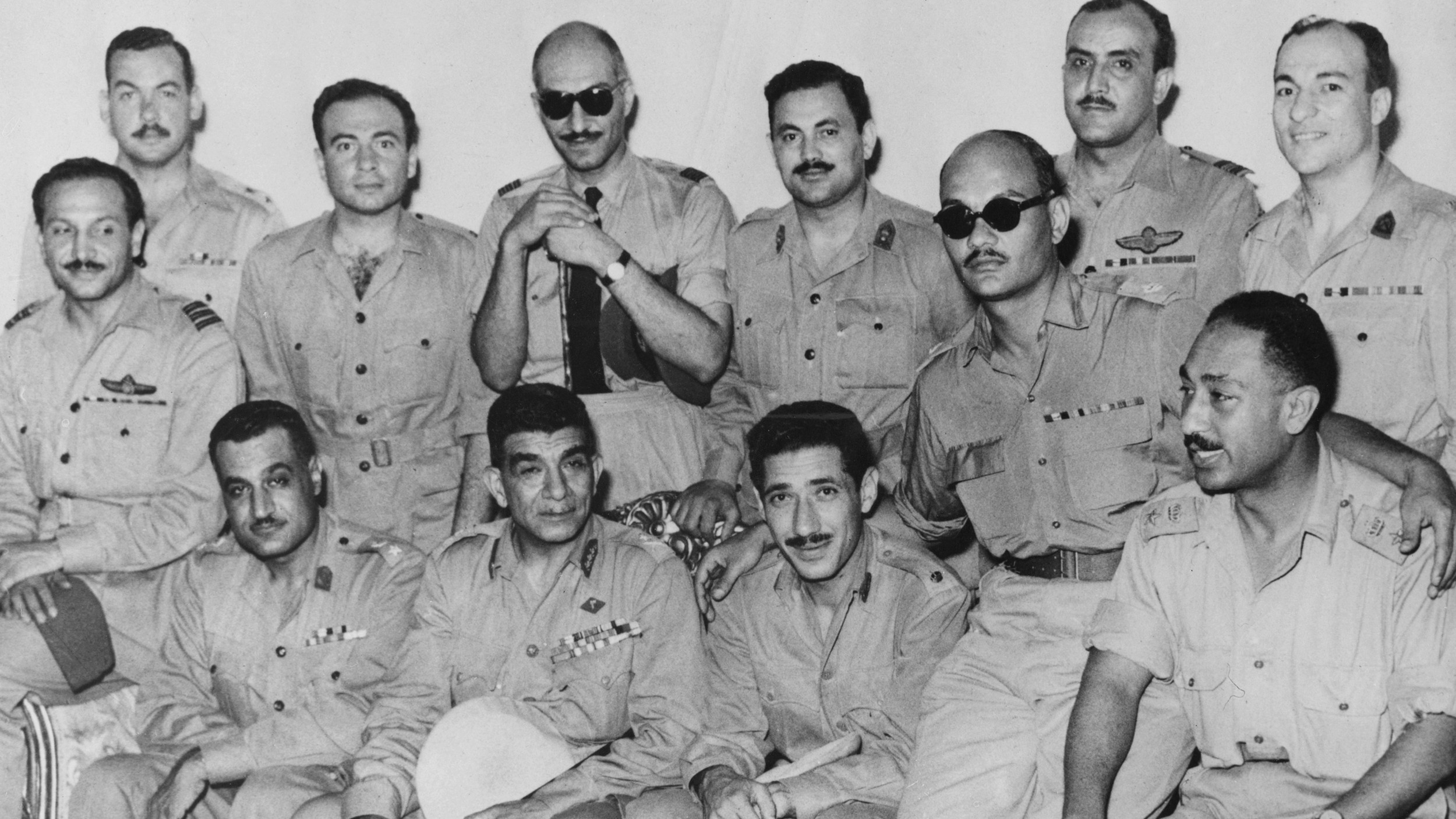

After the Egyptian military’s Free Officers Movement overthrew the monarchy on 23 July 1952, contradictions emerged within the movement’s ranks.

The official leader of the Free Officers, Mohamed Naguib, called on the officers to return to their barracks and hand over power to civilians. However, another officer, Gamal Abdel Nasser, regarded their class as the most worthy of ruling the country.

While the officers, led by Naguib and Nasser, initially allied themselves with the Muslim Brotherhood movement, they began consolidating power and dissolving other political parties during this brief alliance.

The first was al-Wafd, which had led most parliamentary governments before 1952. Workers and communist movements were also suppressed.

The Nasser-led contingent followed up these actions by expelling Naguib and abolishing the Muslim Brotherhood. These moves enabled Nasser to construct a new political regime based on personal rule and military intervention in politics and governance.

His regime relied heavily on backing from the Soviet Union and sloganeering, nominally upholding "free Palestine" and "the struggle against reactionary Arab regimes" to maintain populist support and silence voices calling for democratic reform.

The relationship between the president and the military requires further research to determine who controls the other: the president or the army?

In his quest to consolidate his grip on power, Nasser even clashed with other members of the officer corps, like Defence Minister Abdel Hakim Amer. It took Nasser well over a decade to finally gain control of the army, which only occurred following its resounding defeat in the 1967 war with Israel.

Nasser promised to establish a modern democratic state in what became known as the March 1968 Declaration. However, the declaration was merely a formality. The same repressive measures led by security and intelligence agencies persisted.

In 1969, the regime established the army’s Central Security Forces, which operated under the Interior Ministry. This agency was tasked with suppressing protests and political opponents.

Military business

Although Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, is often most remembered for the ways in which he diverged from his predecessor, Sadat’s rule merely continued many of the practices Nasser had begun.

Sadat similarly eliminated political rivals he felt threatened his rule, even going so far as to regularly replace military commanders to ensure loyalty and prevent a potential coup, which he felt a long-serving commander could plan.

Sadat also hired civilians and reduced the number of military ministers in general. Indeed, Sadat’s divergence from Nasser’s rule involved a similar process of replacement: switching out Soviet backers for American ones, though Sadat’s reliance on global powers was considerably higher than Nasser’s.

Sadat also embraced a policy of liberal, economic “openness” that would allow a small elite to acquire exorbitant wealth. Openness has had severe consequences for the military, whose leadership has chosen to participate in economic affairs.

In 1981, the Public Service Programs Organisation was founded, granting the army financial independence from the national budget. This allows the military to operate its economic programmes with no civilian oversight, and protect the economic interests of a group of military generals who run large corporations.

Under Hosni Mubarak, the army’s economic activity vastly expanded, resulting in a very different military with a broad spectrum of privileges

The 1979 peace agreement with Israel, signed under Sadat’s rule, reduced Egypt’s national spending on the military, subjecting the army to American dependence for money, weapons and training. The US justifies aid to Egypt as an investment in regional stability, based mainly on cooperation with the Egyptian army and on maintaining the Egyptian-Israeli peace.

The army’s strategic direction has changed, and it has an interest in preserving its economic interests, and the regime that protects it.

Under Sadat’s successor, Hosni Mubarak, the army’s economic activity vastly expanded, resulting in a very different military with a broad spectrum of privileges. It became an army that would not get directly involved in politics. Rather, it protected the regime against internal opponents, especially Islamists. It also represented a strong and independent economic player. The military business was exempted from paying any fees or taxes and protected from any accountability.

Lessons not learned

There are two significant lessons to be drawn from the previous era.

First, any political movement’s alliance with the military to silence and suppress another civilian-led movement harms both movements.

The politicisation of the military has had devastating consequences on civilian-led movements and attempts to transition to a democracy. The army, the only organised force, has used these transitory moments to enter and fill the void left by the repression of these movements.

Second, the military’s intervention in politics ultimately serves only to create an authoritarian regime based on "personal rule". A deal is struck whereby the army protects the regime in exchange for the ruler guaranteeing the military a large degree of privilege for itself and its affiliates. In fact, the autocratic ruler harms both the polity and the army.

Close ties between the Egyptian and American armies ensure that the military remains loyal to the regime (and vice versa). Civil politicians have learned nothing from this history. The same cycle was repeated in the aftermath of the 2011 revolution.

While Egypt’s political landscape changed for some time following the 2011-2012 elections, a strong relationship between the Egyptian and American armies remained.

The then-ruling military junta, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), was able to reach an agreement with the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists to pass the "transition road map". That enabled the SCAF to govern, preserve its privileges, and even unilaterally codify them into a series of laws and the 2012 constitution.

The SCAF then allied with a movement calling to remove the Muslim Brotherhood from power in 2013. The defence minister at the time, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, rose to power and, like Nasser and Sadat before him, eliminated his SCAF rivals and established his personal authority, supported by the intelligence and security agencies. Sisi then broadened the military’s privileges to prevent further coups.

Considering the extensive privileges granted to the military in the 2019 constitutional amendment, along with several statutes, the current relationship between the president and the military requires further research to determine who controls the other: the president or the army?

Civilians bear primary responsibility

Sisi’s consolidation of power would not have been possible without generous regional support and favourable geopolitical conditions.

Sisi’s consolidation of power would not have been possible without generous regional support and favourable geopolitical conditions

The great international powers have prioritised their economic interests and arms deals with Egypt over human rights and democracy, and the regime has used anti-“terrorism” rhetoric to strengthen its rule and suppress human rights.

Security ties between Israel and Egypt have grown increasingly strong, as both armies coordinate to fight “extremists” in the Sinai.

Egypt’s civilian opposition forces bear the primary responsibility for the country’s repeated failures to achieve a democratic transition. They overlooked two critical facts. First, every president selected through means other than free elections has only ever been concerned with consolidating personal power and preventing a coup by appeasing the military. And second, Egypt has an important geostrategic position that makes any political change more than just an internal process.

Until political movements recognise these crucial facts and respond accordingly, Egypt’s political process is doomed to repeat a now seven-decade-long cycle.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.