Egypt under Sisi: Anatomy of a military regime

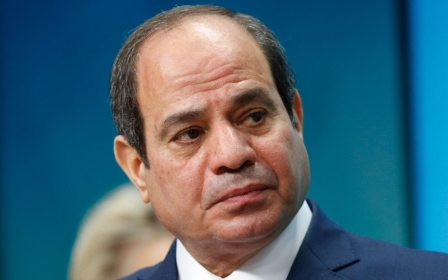

Chronicling the militarisation of the Egyptian state under Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Maged Mandour, in his book Egypt Under el-Sisi: A Nation on the Edge, provides a detailed account of the economic, legal and political structural changes introduced since Sisi came to power after the 2013 coup.

Mandour examines the nature of the military regime and presents two main arguments.

The first counters the scholarly assumption that the 2011 uprising created a revolutionary situation without revolutionary outcomes. Mandour contends that the uprising did indeed result in a revolutionary outcome, though not the one desired. It led to an unprecedented intensification of the state's militarisation, marking a significant departure from Gamal Abdel Nasser’s military legacy.

The second argument suggests that despite the consolidation of Sisi’s regime, it remains vulnerable to change due to economic rather than political pressures.

Drawing on Samuel E Finer’s (2002) classification of military regimes, Mandour categorises Sisi’s rule as a direct military regime, unlike the dual/indirect systems of Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak. The first four chapters explore the distinctive characteristics of Sisi’s military regime.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Chapter one traces the state’s political evolution and the military’s status up to the 2013 Rabaa massacre, focusing on its ideological discourse of hegemony.

Chapter two discusses the militarisation of various state branches, while chapter three addresses the use of violence for public repression. Chapter four examines the militarisation of the economic sphere and the rise of aggressive military capitalism.

In each chapter, Mandour highlights how Sisi’s regime has intensified its military grip over public and economic spheres compared to its predecessors since 1952. In the final chapter, he explores the future prospects of the current regime and the possibility of a democratic transition.

Reflections

The book’s main theoretical contribution lies in its application of Finer’s categorisation throughout the chapters.

Mandour’s examination of the Sisi regime’s ideological foundations and the legal and economic tools of militarisation is a delight for readers interested in modern Egyptian politics. However, the book's theoretical analysis is where it falls short.

While the author’s explanation for why Sisi’s regime fits Finer’s category of direct military rule is well-argued, his use of Antonio Gramsci’s concept of passive revolution as a second theoretical pillar is insufficiently explored and somewhat ambiguous.

Mandour acknowledges that key elements of Gramsci’s definition do not fit the current Egyptian regime, such as reliance on a non-ruling elite to govern and the existence of a non-hegemonic society, raising questions about the relevance of Gramsci’s concept to the discussion.

Despite recognising this limitation, Mandour concludes that the coup brought about elite-driven radical changes without popular participation - a point that could be better supported by existing literature on authoritarianism and military rule in the Middle East, rather than the notion of passive revolution.

The book occasionally references other key scholarly works, such as Gramsci’s definition of the state and Timothy Mitchell’s Rule of Experts on the nature of capitalism. However, these insights are limited and remain almost unexplored. The absence of extensive theoretical discussions could be justified by the book’s journalistic nature and motivation to address non-specialised readers.

The book's most significant reflective section appears in the final chapter, where Mandour delineates three potential scenarios for Sisi’s regime. This section transcends mere descriptive narration of state policies, venturing into analytical reflections on Egypt's prospects for democratic transition.

Here, Mandour’s argument regarding the regime's vulnerability due to its military capitalism - a concept astutely describing the military's neoliberal control over the economy - comes into play.

This chapter addresses four pivotal questions. How will the regime change? Will it collapse in a wave of mass bloodletting, akin to a Libya-like scenario? Will it gradually decay until it can no longer withstand popular pressure and then collapse? Or will it reform itself, evolving into a dual military-civilian rule system, potentially achieving long-term stability?

Mandour posits that elite-led reform is unlikely due to the profound militarisation of the state under Sisi, which has resulted in unchangeable political and economic realities. The military establishment’s vested interest in maintaining the status quo and the absence of organised opposition further solidified this regime as a political reality that could persist beyond Sisi’s rule.

Accordingly, Mandour identifies only two plausible change scenarios: an external shock, such as a regional war; or internal decay, potentially induced by external pressures similar to the 2011 uprising.

Two scenarios

While compelling, Mandour’s analysis neglects several critical issues.

The two proposed scenarios, although distinct, are interrelated in terms of an existing external threat to the regime, inducing top-down reform. In both scenarios, his analysis overlooks the impact of regional security arrangements established post-Arab Spring.

He insufficiently examines the regional transnational tools of surveillance and repression that emerged after 2011 among Arab countries, designed to sustain authoritarianism and suppress political Islam. The analysis is silent on the diminishing efficacy of protest as a mechanism for change in the Arab world, making another uprising seem far-fetched.

Furthermore, the challenges to elite-led reform do not fully consider the possibility of elite factionalism - a plausible scenario even in the most repressive regimes - or the resurgence of Islamists as a potential organised political force. An Islamist comeback is not just about the Muslim Brotherhood but a broad spectrum of Salafi groups. Even a superficial return of Islamists could suffice to introduce a counterbalancing power.

Elite-led reform might be possible through military personnel keen on establishing a civilian facade and neutralising rival military figures by facilitating a decorative return of Islamists. Unfortunately, this part of the book stands alone without sufficient elaboration from the broader literature on authoritarianism and civil-military relations.

The book’s methodology presents another shortcoming. While it relies on a rich set of media and primary sources, the author neither addresses his method of data analysis nor the criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of these sources in the book’s introduction. This omission significantly affects the book’s scholarly rigour.

Despite this, Mandour's book provides a detailed portrait of the anatomy of Sisi’s military regime and offers a foundation for future theoretical explorations into democratic transitions and reform possibilities in Egypt.

The book is a key text for Middle Eastern scholars seeking rich case studies on military-civil relations.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.