Algeria's Hirak movement won. Now its time is over

The lifecycle of the Hirak has come to an end. The movement behind the abdication of former President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in April might be alive in spirit, and may even provide a source of political inspiration for decades to come - but Algeria must face the music: the Hirak as a political movement is a thing of the past.

The time has come to look at what we have learned and to make adjustments for the country’s new political landscape, a situation requiring the examination of possible new perspectives and means of political action.

After a year of demonstrations that broke through a ludicrously immovable political impasse, the Hirak movement has died a natural death. The inspirational “revolution of smiles” not only toppled the Bouteflika regime, but it brought the former ruling elite to their knees; some were even put on trial. It was totally unexpected and achieved without violence.

This alone makes make it a milestone in recent Algerian history.

Historical significance

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

To say that the Hirak has come to the end of its natural life in no way diminishes the historical significance of the Algerian movement. Nor does it infer that the Hirak was a failure - quite the opposite is true.

It is simply a question of admitting that it is over, just as the “historic” figures who sparked the Algerian War on 1 November 1954 - Hocine Ait Ahmed, Mohamed Boudiaf, Mohamed Khider, Krim Belkacem and others - determined that the mission of the National Liberation Front (FLN) had ended with the winning of independence from France, and that the party’s role was consequently over.

The Algerian people were marching for recognition, for dignity and freedom, for the right to voice their feelings and to realise their goals

On 1November 1954, those emblematic letters, FLN, burst onto the world scene, acquiring over the course of the next decade a unique aura - a potency that few other symbols from the mid-20th century could hold a candle to, in spite of many tragedies, major events and powerful emblems.

The three letters were the embodiment of the Algerian people’s aspirations for freedom, of their desire for independence. They were the quintessential representatives of sacrifice and abnegation, of anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggle, of solidarity with the oppressed and the masses against the ruling elite.

The acronym was fraught with meaning, its value and intrinsic worth so obvious that its mere mention was, for a long time, enough to determine whether you were a supporter or a detractor, a believer or an opponent.

The FLN was more than a party. It was an identity, a label, a signature. But its remarkable aura was rapidly overshadowed, and then called into question, as the party came to be synonymous with authoritarianism.

A mindset and an objective

Soon after independence, some of the FLN’s most influential members either broke with the party or joined the opposition. Later, the FLN’s name became conflated with a dubious mix of progressive rhetoric and authoritarian policy.

Under the presidency of Chadli Bendjedid, it would - justifiably or not - become the symbol of an organisation on its last legs, of a party declaring its willingness to embrace change but incapable of implementing it. It sank for good when FLN-backed troops fired on protesters during the October 1988 riots.

In the space of two decades, the FLN had evolved from a liberation movement to an intransigent force hostile to progress, whose longevity was written into its DNA: it was above all a “system” for creating an army and a government.

The Hirak movement is an altogether different beast, born of a mindset and an objective, and lacking any organisational model whatsoever. It would be shaped by a series of rapid, historic changes that would see its natural lifecycle come to an end within months.

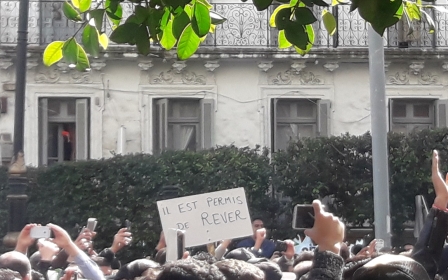

On 22 February 2019, millions of Algerians took to the streets, rising up against the humiliation of a fifth Bouteflika mandate - against the corruption, mismanagement and injustice of the Algerian political system. It was a broad indictment; a rejection of both the ruling elite and the ham-fisted opposition.

The Algerian people were marching for recognition, for dignity and freedom, for the right to voice their feelings and to realise their goals. For the first time since independence, the people had taken to the streets. Millions of Algerians of all walks of life, of all generations and persuasions, marched together to say: “Enough is enough!”

An authentic and silent Algeria

But who were these demonstrators - left-wing, right-wing, progressive, conservative, secular or Islamist? Clearly, the Hirak was not defined by one particular political or religious orientation, despite the media’s clever portrayal of the movement as non-violent, young and celebratory.

The truth is, the Hirak was first and foremost the face of an authentic and silent Algeria - an Algeria unaccustomed to taking centre stage.

The army could see what was coming. The body that had accompanied the many aberrations of the Bouteflika regime found itself forced to carry out major structural changes. Consultations began in March 2019, and conclusions were delivered by early April. Horses were changed mid-race. Power was openly seized by the military, albeit with a minimum of ceremony. Bouteflika was given the boot, and Abdelkader Bensalah was put in place.

Political currents and processes had gradually managed to supplant the Hirak movement - speaking in the name of the protesters

The army was invigorated by what it saw as its calling and its own historical significance. As a show of good faith, five major resolutions were announced: no fifth term for Bouteflika; an immediate end to his fourth term; the enforcement of Articles 7 and 8 of the Constitution vesting the people with constituent power; a peaceful transition of power with the promise of no bloodshed; and the implementation of a sweeping anti-corruption campaign.

The deal put forward by the army would have been unimaginable just two months earlier, and it appeared to meet the objectives of most demonstrators.

Algerians were struck by one thing in particular, a historical first for the country: dozens of ministers and high-ranking officials, including former prime ministers and intelligence chiefs, along with senior officials from the administration, army and security services would face trial. It was nothing less than inconceivable.

Riposte of the power brokers

But the military’s deal was rejected by the people speaking in the name of the Hirak. It is impossible here to go over the myriad rationales behind the refusal; we will mention just two.

Firstly, political currents and processes had gradually managed to supplant the Hirak movement - to emerge as its new voice, speaking in the name of protesters. New watchwords, including “transition”, “constituency” and “negotiation” (with self-proclaimed associates from within their own ranks) were imposed. These demands were perfectly legitimate perhaps, and they had been heard from within the Hirak from the very start - but they had not been met with unanimous agreement.

Next came the riposte of the power brokers, who had the most to lose with the end of the Bouteflika regime. The stakes were high, and they acted accordingly. Hoping to steer the Hirak in a direction more favourable to them, they threw their weight behind the Hirak protesters who were challenging the validity of the newly imposed military regime, led by former army chief of staff Lieutenant General Ahmed Gaid Salah.

The consensus of the early days from which the Hirak had drawn its strength was gone. Fewer people were taking to the streets. In Algiers, the number of protesters had dropped from millions to tens of thousands. The drop was even more pronounced in the countryside - and yet, it was precisely the scope of the demonstrations in small and medium-sized cities throughout Algeria that had created the unstoppable momentum of the Hirak.

Lack of political vision

Efforts to prevent the December 2019 presidential election, followed by the uncertainties of the Covid-19 pandemic, brought the process to a halt. The Hirak is no longer a popular street movement; it has been usurped by a handful of activists and diehards. Many had challenged the ruling elite of the Bouteflika regime, but they were overwhelmed by the dynamics of the popular movement.

Why are they so desperate to see the Hirak continue? For some, it offers political legitimacy, which is all they have left. For others, it emerges from their inability to envisage a long-term militant strategy; they prefer to proceed in swoops and incursions, to seize every opportunity to strike.

Others still rightly believe that Algeria failed to cash in on the movement to give the country a new direction, and they are still hoping to change course

Others still rightly believe that Algeria failed to cash in on the movement to give the country a new direction, and they are still hoping to change course.

But the main reason resides in the country’s inability to envisage a different kind of political future - a future where concrete, well-thought-out projects can be elaborated and set down. This requires reflection, consultation, negotiation and compromise - qualities sadly lacking in Algerian political life.

Be that as it may, it is perfectly legitimate to lay claim to the spirit of Hirak today, just as it is to appropriate the spirit of 1 November or of the 1956 Congress of Soummam (a meeting of the principal leaders of the Algerian war for independence).

But to lay a claim to the Hirak movement itself is tantamount to behaving like the FLN stalwart, Mohamed Cherif Messaadia, who appropriated the FLN acronym 25 years after Algerian independence.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article was translated by Heather Allen and condensed from the MEE French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.