Facebook and Twitter can't uphold standards with offices in repressive Middle East countries

Last week, activists and journalists launched a campaign on Twitter, calling on the platform to relocate its regional office in the Middle East from Dubai.

In today’s digital reality, freedom of speech and expression are increasingly determined by social media companies

Using the hashtag #Change_Office_Twitter_Dubai, many activists said Twitter "manipulated" their tweets and removed hashtags criticising their governments. The campaign was launched following the deletion and suspension of hundreds of accounts of political opponents and activists.

In today’s digital reality, freedom of speech and expression are increasingly determined by social media companies

Recently, Facebook rescinded a policy banning false claims in political advertising. The move raised a few eyebrows. But questionable Facebook acts are not new: its crackdown on Palestinian content, reportedly via an algorithm that targets terms such as “resistance”, “martyr”, and “Hamas” - no matter the context - results in the removal or blocking of posts, the banning of users’ accounts, and, in the worst cases, arrest.

In response, activists have launched a campaign with the hashtag #FBblocksPalestine.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A digital reality

In today’s digital reality, freedom of speech and expression are increasingly determined by social media companies entrusted to manage the precarious balance between open communication and censorship of hate speech. Yet without a code of conduct ensuring protection of human rights, these private companies too often cave to pressure from governments and allow their channels to be used as instruments of repression.

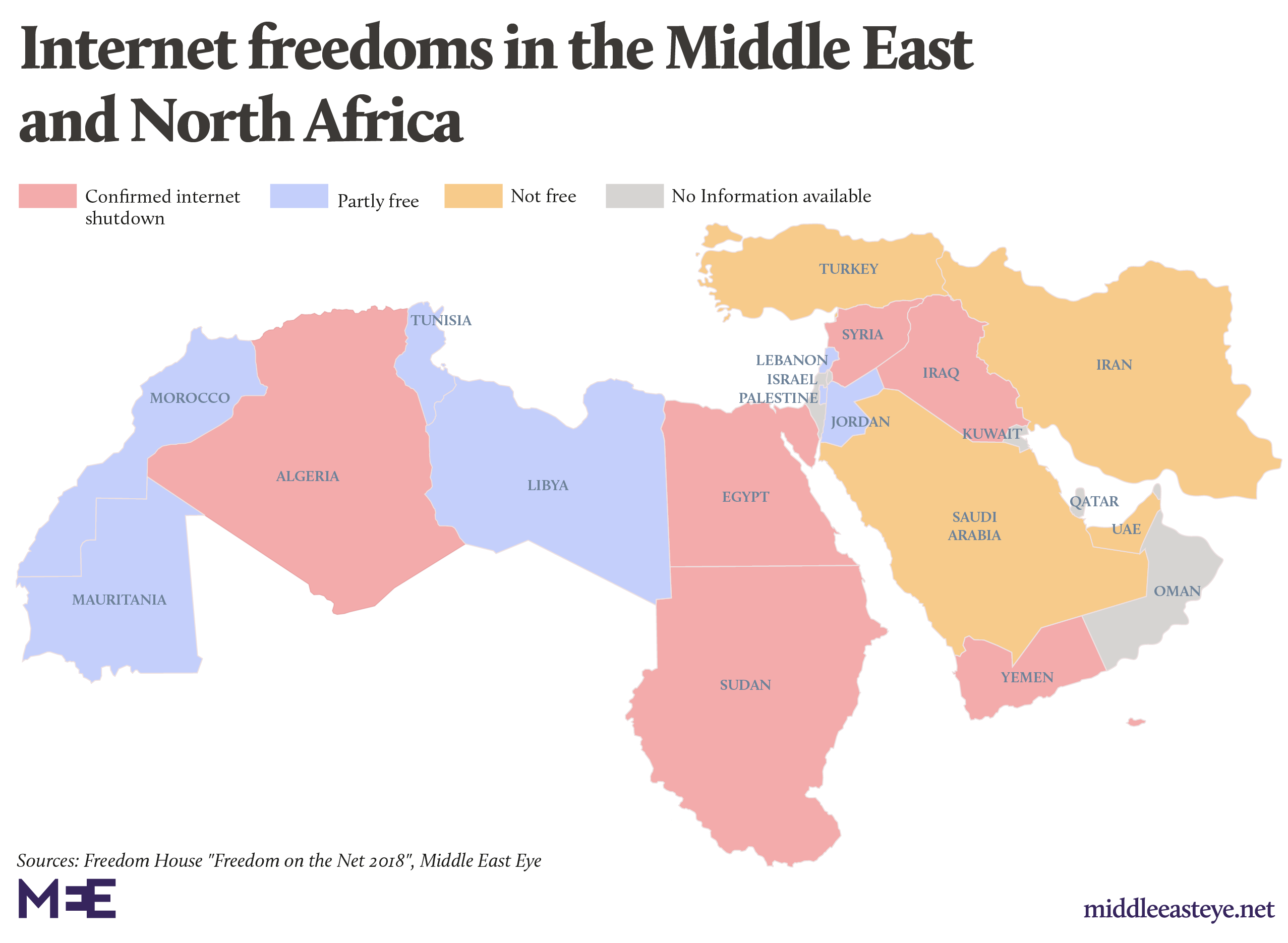

This is particularly true when digital giants locate headquarters or regional offices in countries guilty of crushing freedom of expression.

Analysis conducted by ImpACT International for Human Rights Policies, a London-based think tank, shows that when Facebook and Twitter locate offices in countries such as Israel, the UAE and Saudi Arabia, the companies can be enlisted by the governments to silence dissenters and political opponents.

The most recent and egregious examples are found in Israel, where Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Intel are among more than 300 multinationals that have opened research and development facilities. Facebook, for instance, opened a regional office in Tel Aviv in 2013.

Three years later, a team from that office met with Israeli Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked and Public Security Minister Gilad Erdan, who spearheads the fight against the boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement. The aim of the meeting, according to a statement released by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's office at the time, was improved "cooperation against incitement to terror and murder”.

In reality, what resulted was a concerted effort to suppress Palestinian social media activity focused against the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the blockade of the Gaza Strip.

Staggering racism

In 2017, a report by the Israeli Ministry of Justice said its cyber unit documented 2,241 cases of “objectionable” online content shared by Palestinians and succeeded in removing 70 percent of it.

Last year, 7amleh, the Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media, reported that Israeli authorities arrested around 350 Palestinians in the West Bank on charges of “incitement” because of their posts on social media - up from 300 arrests in 2017.

In contrast, critics point out that violent threats and other harassment on social media by Jewish Israelis rarely attract scrutiny. 7amleh documented a “staggering” increase in incidents of racism and hate speech in pro-Israeli social media, calculating that an inciting post is made against a Palestinian every 66 seconds.

The group counted 474,250 posts that insulted or advocated violence against Palestinians. In all posts about "Arabs", one out of 10 contained hate speech or a call for violence such as rape and murder.

No immunity

Twitter is also not immune to influence by repressive host governments. For example, one day before Twitter opened its regional office in the UAE, prominent economist Nasser Bin Ghaith was arrested for tweets critical of his own government as well as of the Egyptian regime, an ally.

Bin Ghaith was arrested in Abu Dhabi and taken to an undisclosed location, where he was denied access to his family, lawyer, and medical treatment for nearly eight months until he was granted his first hearing. He was sentenced to 10 years and is serving to this day.

With the risk posed by the location of social media companies real and growing, ImpACT is calling for global digital media companies to adopt standards protecting users’ human rights, including freedom of dissent and expression.

Recognising the power of governments to control behaviour within their borders, the organisation also calls on governments to pledge respect for these standards, and for citizens and international bodies to pressure them to do so and monitor their compliance.

However, government participation will take time and will likely be uneven. These companies must thus avoid locating headquarters and regional offices in countries that violate human rights standards, and instead move to those that respect them, such as Scandinavian European countries.

Official repression

Recently, both Twitter and Facebook have taken steps in the right direction. On the day of the Israeli elections, Facebook blocked a “chatbot” from Netanyahu’s right-wing Likud Party account for violating electoral rules, after a message spread by his campaign warned that Arab-Israeli politicians “want to annihilate us all". However, the chatbot function was up and running again very quickly.

Likewise, Twitter suspended the account of former Saudi royal court adviser Saud al-Qahtani, albeit nearly a year after he was sacked over his suspected role in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Twitter also reported that it deactivated 271 “propaganda” accounts linked to Saudi Arabia’s “state-run media apparatus”, as well as others in the UAE and Egypt working to amplify the same pro-Saudi messages.

These are early, encouraging actions, but - given these companies’ past track records - they are not enough. The global marketplace has evolved to the extent that multinational companies must place human rights on par with profits. Hatred, violence and suppression of healthy dissent must not be enabled or allowed to flourish.

The first step is to demand that global companies acknowledge the power wielded by governments and locate their offices away from the reach of official repression.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.