Internet, interrupted: How network cuts are used to quell dissent in the Middle East

As protests against corruption and lack of jobs quickly spread across Iraq last week, at least 165 were killed by security forces. But as unrest grew, demonstrators not only faced tear gas and bullets, but an hours-long internet blackout covering around 75 percent of the country, according to monitors.

Facebook, Twitter, Whatsapp and other platforms were initially blocked, but as mass protests gained momentum, the restrictions developed into full network outages.

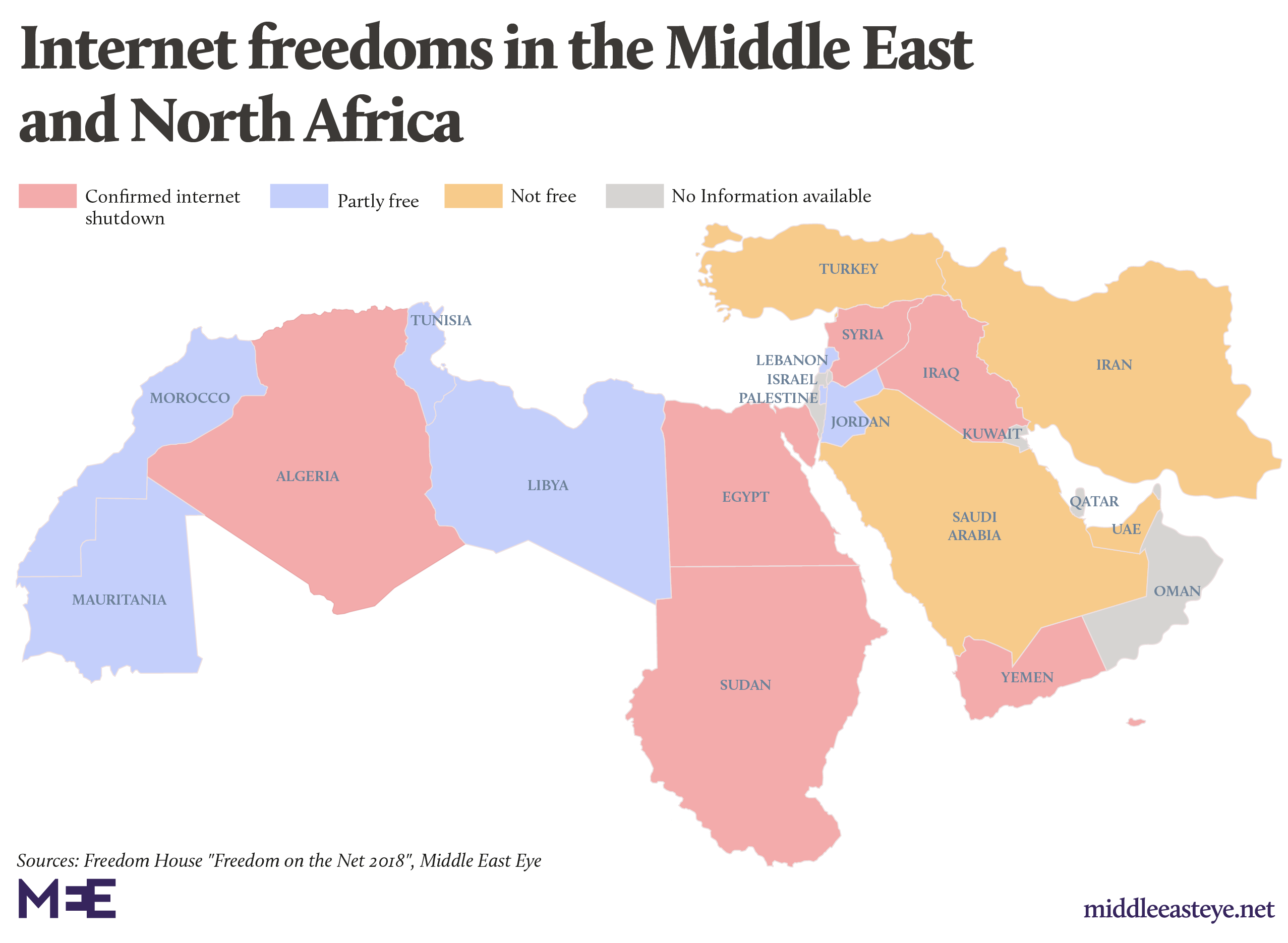

It’s not just Iraq. Across the globe, governments have been increasingly resorting to network shutdowns and access restrictions as a means of disrupting dissent and limiting information accessible to citizens - and repressive governments in the Middle East and North Africa region are no exception.

A rapidly spreading tactic

As a wave of renewed protests against Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi spread across the country in mid-September, Egypt’s major internet service providers restricted access to international news sites which covered the protests, including the BBC and Al Jazeera, as well as social media platforms including Facebook.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In Kashmir, network services have been disconnected for nearly two months since India’s unilateral move to annex the territory in August. Both India and Pakistan have severed access to internet, as India has enforced sweeping draconian restrictions on seven million Kashmiris, including curfews and an increased military presence.

In China, the lead-up celebrations of the 70th anniversary of the communist party’s rule on 1 October saw the country’s “Great Firewall” of censorship further reinforced. Authorities aggressively blocked VPN servers, which many, especially foreigners, rely on to contact their families and to surf foreign websites.

Meanwhile, Sudan has experienced major internet shutdowns throughout the year as mass protests unseated autocratic ruler Omar al-Bashir and continue to oppose military rule.

Sudanese activist Hatim Eujayl told Middle East Eye that the internet shutdowns were particularly extensive on 3 June, when Sudanese forces staged a deadly crackdown on a mass Khartoum sit-in.

“We’d seen social media get blocked before, certain websites restricted,” Eujayl said. But on that day, Sudan witnessed a complete network cut off. ADSL - provided to government offices, banks and very few individuals - was the only remaining connection, prompting many activists to linger around banks to try and get access to the internet.

That day, the sit-in outside the military’s headquarters saw more than 100 protesters killed and a complete lockdown of the capital Khartoum, with arrests, beatings and open fire on passersby.

“The information we lost as a result of the shutdown mostly had to do with the exact nature of the massacre, the details,” Eujayl said. For the Sudanese activist, the goal of the shutdown was to prevent the Sudanese public from seeing “just what level of violence was carried out at the massacre”.

“When the internet was brought back, social media was overwhelmed with new videos… photos,” he added.

Four months later, dozens of protesters remain unaccounted for. Meanwhile, the internet blackout has had long-term consequences on the public perception of the massacre, Eujayl said. According to him, the shutdown was used to “campaign in rural areas and amplify anti-revolutionary state propaganda”.

“And it kind of worked,” he said. Citing his own family from a village in central Sudan as an example, Eujayl said residents there by and large didn’t consider the 3 June massacre a crime. State propaganda said the demonstrators had been engaged in “illegal” activity, and according to Eujayl, the villagers had no idea about the scale of the death toll.

“They didn’t have an alternative source to tell them those things weren’t true.”

A long history of censorship

As shocking as the increase in shutdowns has been to many, this tactic has a long history in many countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

Access to the internet in much of the region was long restricted to internet cafes, and in many cases was only accessible to the wealthy. For Middle East and North Africa consultant Nasser Weddady, restrictions on internet services are “as old as the internet itself”.

Under Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, internet access was initially banned and then tightly monitored. When the Libyan uprising began in 2011, long-time ruler Muammar Gaddafi cut off internet access to large parts of the country altogether, keeping them offline for six months. That same year in Egypt, Hosni Mubarak shut down the internet for five days in an attempt to prevent the planned protests against his decades-long rule.

“In Syria, access to the internet was originally limited to government officials and it was the same in Mauritania,” Weddady told MEE.

Total shutdowns haven’t been the only practice imposed on citizens. Intentionally slowing down the speed of internet services - known as "throttling" - is also a common tactic, making webpages take longer to load and limiting access to tools that need speedy internet. This renders internet surfing so frustratingly slow that people are discouraged from doing so.

Alex Gladstein of the Human Rights Foundation told MEE that it is one thing to have internet access cut off or disrupted - but things can be much worse when the internet is available, but tightly monitored, leading users to self-censor.

Restrictions on messaging and communication apps - such as blocks on WhatsApp and Viber in the UAE - force people to use local telecommunication networks for calls, which are far easier to intercept.

As connectivity has spread, restricting access became normalised, particularly in Gulf monarchies, which “threw money at the problem” early on, according to Weddady.

McAfee’s SmartFilter technology, which blocks access to content from designated sites, has been a favourite of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait and Sudan, while Canadian Netsweeper software was the favoured choice for authorities in Yemen, Qatar and the UAE to carry out similar content filtering.

According to Jillian York, the author of an OpenNet Initiative report, “virtually anyone can manipulate these systems to get content blocked, having a chilling effect on free speech”.

“Saudi can block a specific post or link in a post. They are far more sophisticated in their censorship, allowing them to police content on a large scale without having to shut everything down - they are microtargeting,” Weddady said.

Iran has also been using throttling for years, particularly in anticipation of protests, with Telegram and Instagram also being blocked before major protests.

For governments, using throttling tactics rather than complete internet shutdowns can have distinct advantages. These methods are difficult to distinguish from ordinary disruptions, and hence less likely to lead to widespread condemnation.

These targeted techniques have affected Middle East Eye, whose site has been blocked in the UAE since 2015 after publishing articles exposing surveillance and human rights abuses there. There have also been recurring reports of MEE being blocked in Saudi Arabia and Egypt over the years.

This year, NetBlocks - a civil society group focused on digital rights, cybersecurity and internet governance which has monitored internet shutdowns globally since 2017 - observed increasingly sophisticated and targeted restrictions, cutting off specific demographic populations or restricting specific types of content as a means of social control.

Meanwhile, “technical advances means we are better equipped to track these incidents now,” Netblocks executive director Alp Toker told MEE.

At the time of writing, NetBlocks itself had recently been the subject of an attack, with pages of its website offline for several hours.

Despite all this, “the reality is that it's difficult to tell if we're in the midst of a global network disruption crisis,” he added. “There has been no effort at systematic record-keeping until recently, and evidence suggests that politically motivated internet shutdowns have been severely under-reported in the past.”

A ‘human problem’

In addition to attempts to counter popular dissent or unrest, network disruptions are also used in parts of the region during exam periods to counter cheating in schools. Iraq and Algeria both employ this tactic often.

According to Toker, such shutdowns squander “tens of millions of dollars of their citizens' money, causing businesses to go bankrupt and destabilising entire industries by shutting down internet access to prevent cheating in high school exams”.

In other places, elections are a prime time for shutdowns. In Mauritania, the government cut off the internet on the day of the most recent election, with the shutdown lasting around a week.

'At their core internet shutdowns remain a human problem'

- Alp Toker, Netblocks executive director

“They [the government] said they were worried about hate speech and racial tensions,” Weddady said of the Mauritania shutdown, adding that the move was a way for the government to navigate post-election unrest.

Network disruptions have a widespread impact on the economies of affected countries; the more mature the online ecosystem, the greater the cost of internet shutdowns.

According to a 2016 report from Deloitte, in places with "medium" levels of internet connectivity, the average GDP impact of shutdowns amounts to $6.6m per 10 million inhabitants, and $23.6m per 10 million inhabitants in highly connected countries.

But shutdowns and disruptions mean more than monetary losses. “An internet shutdown might cast the integrity of an election in doubt or lead to loss of life,” Toker told MEE. “Disrupting telecommunications infrastructure tends to increase violence and engender mistrust between authorities and the citizenry rather than quell unrest.

“At their core internet shutdowns remain a human problem, which can only be addressed through transparency, public interest journalism and technical advocacy,” he added.

Solutions emerge

In many countries, the only or most accessible options for getting online are government-owned or sanctioned - but this control is increasingly being challenged.

In Sudan, the network disruptions didn’t stop protesters. Eujayl pointed at how the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), one of the leading organisations in the protest movement, changed its strategy during the internet cuts, directing protesters to advertise demonstrations on its behalf.

“Protesters would go door to door, they’d make handouts and flyers… they [the SPA] would announce activities weeks in advance, giving protesters time to advertise,” Eujayl told MEE.

People are already finding ways to circumvent restrictions, using apps like Firechat - an "off the grid" messaging app - that don’t require internet access. Wireless mesh networks have also become a major part of pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong.

“The potential of decentralised internet has not been realised,” Gladstein said. “[But] we are seeing healthy global competition for private non-governmental internet service providers, and in ten years we will have a bunch of options for getting on the internet.

“The ability of a dictator or even a democratically elected government to disrupt access will become impossible as internet access proliferates and hardware gets cheaper,” he added, sounding hopeful.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.