Sudan's diaspora fights to fill information black hole created by internet blackout

Thousands of Sudanese, both inside and outside the country, wait anxiously for the next ding on their phones alerting them to new videos arriving through Telegram, the messaging app being used to document the violence rained down on protesters over past weeks.

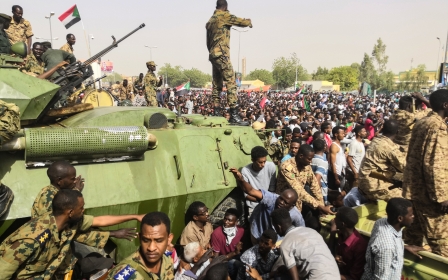

The Telegram channel, named Military Council Violations, emerged after Sudanese forces killed at least 128 people while forcibly dispersing a sit-in at the heart of the capital Khartoum on 3 June, then closed off the internet as they tore through the city, forcing its protesting residents into hiding.

The team behind the documentation effort have been collecting, verifying and then disseminating footage of previously unseen angles of the crackdown which, they hope, could be used as evidence in an investigation.

The volunteers had participated in the protests, but many of them were outside the country when the crackdown started and felt moved to act.

“We couldn't believe what we saw, all the Facebook Lives had sounds of loud screaming, continuous shooting, fires spreading. We watched as two of our friends were shot!” the Telegram team told Middle East Eye through email.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

“We didn't do anything for a whole 24 hours. After a while we knew the military had cut the internet services and was working to erase traces of its crazy crime from the media. At that time we decided to take action.”

The Telegram group are not the only ones, with many in the Sudanese diaspora organising to fill the information gap left by the internet blackout.

Dozens of campaigns have been launched to help document violence, raise awareness about the country’s protest movement and rally support for doctors trying to treat hundreds of injured with limited supplies.

A small minority of people have been able to stay online because their internet services had not been cut or because they could use the international roaming services of foreign mobile providers.

That has helped the Military Council Violations team and others collect some of the footage from the crackdown that was not immediately uploaded during the protest’s dispersal.

Within a few hours, thousands were joining the channel and sending them material which would often end up on other pro-protester accounts on popular social media platforms.

The videos show the moment Sudan’s paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) started firing on protesters, the chaos inside on-site clinics trying to treat the wounded, uniformed RSF members burning tents, and the mass arrests of protesters. More than two weeks later, more footage is still emerging.

Not all of the footage is from the sit-in. Some of it shows RSF forces, also known as the Janjaweed after the militias they were formed from, attacking residents in other parts of Khartoum where, until protests began to return to their previous numbers this week, many had been hiding inside their own homes.

If people get tired of the trend, this is not a trend to us, we’re fighting

- Ebaa Elmelik, co-founder of Media for Justice in Sudan

The internet blackout meant news of what was happening, and where, has played on the nerves of Sudanese living abroad, often unable to contact their family and friends inside the country.

The Sudanese Abroad Students and Alumni Association (SASA) was initially set up when protests against now-ousted president Omar al-Bashir began in December 2018, aiming to connect networks of Sudanese youth abroad, but this month’s crackdown has turned it into a de-facto fact-checking service.

“When the massacre happened on 3 June we shifted our focus to verifying news,” SASA member Ola Idris told MEE. “We had some people on the ground who were sending videos and always calling us telling us what was happening.”

The group used the family connections of members to phone directly and get accounts from inside Sudan, and raised money to ensure people inside Sudan had phone credit to communicate with them.

Idris said the group had to take on the role because they were worried the violence would not be covered otherwise, especially with the internet blackout.

She also pointed out that the military council raided media offices before the sit-in's dispersal and expelled Al-Jazeera. In the past few days, the Sudanese Journalists Network has also condemned mass firings at state news agencies.

“They think that if you cut off the internet there isn’t a way to document the atrocities inside and they could get away with it and not be held accountable,” she said.

“The diaspora was quick to make sure they used their connections with their family or whatever to make sure it got out.

“It was basically a bridging point between the youth in Sudan and the youth outside.”

Forced into action

Even as the internet was cut, interest in Sudan, where protests had gone almost six months with limited coverage, spiked because of the deadly crackdown against the sit-in.

But with many of the Sudanese social media users who had for months been most active in providing updates on the protests now silenced, many in the diaspora felt compelled to take up the task.

“I think it forced a lot of us in the diaspora out of feelings of helplessness and into more action,” said Ebaa Elmelik, co-founder of the campaign Media for Justice in Sudan, who are calling for members of the diaspora to go out in public and educate people by holding up signs inviting others to ask them about Sudan.

In one dramatic example, awareness about Sudan spiked when a campaign by the friends of Mohammed Mattar, an engineering student who was killed on 3 June, started a campaign to turn their social media profiles blue in respect to his favourite colour.

And after singer Rihanna posted in support of Sudan, a raft of others began doing the same, though there were also questions about whether some of the celebrities were confusing the message.

“I welcome and appreciate all celebrity efforts to shed light on Sudan," said Elmelik.

"However, we ask that celebrities advocate for the actual demands of Sudanese people instead of taking the 'Pray for Sudan' shortcut.

“We’re telling the world what we most need now and we’d like them to show real support for that.”

Elmelik said their campaign was inspired by discussion corners at the sit-in, which lasted almost two months before being destroyed, and hoped to utilise the large Sudanese diaspora to engage people about the glimpses of Sudan they might have been getting through social media, such as through the “Blue for Mattar” campaign.

'This revolution will win'

The diaspora has been involved in supporting the Sudan protests since the very beginning, but the dispersal of the sit-in, and the internet blackout that cut off activists inside Sudan from the rest of the world, has strengthened the resolve of many.

Idris said that support is going to remain long-term, even if the engagement of others on social media fades with time.

“It’s really important to know Sudan is not alone because the diaspora is part of Sudan,” she said. “If people get tired of the trend, this is not a trend to us, we’re fighting. This revolution will win.”

The team running the Military Council Violations channel said they hope they can build on the work they have been doing.

They have already expanded by setting up Facebook and YouTube pages, and translating all of their captions into English, and hope the work they are doing can provide the evidence for future investigations into the violence.

“We want the world to name things by its names, they are not RSF, they are Janjaweed militia,” they said, referring to the militia accused of war crimes in Darfur, which forms the main part of the paramilitary force putting down protests.

They have begun researching which international bodies might be approached for an investigation and what standards of evidence are required.

“We hope our channel becomes a source of evidence, documenting those crimes for related parties from international humanitarian communities and investigating bodies, and gathering more global empathy and spotlighting our great peaceful uprising.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.