The Fate of Abraham: Why the West should rethink its relations with Islam

Peter Oborne is a born-again journalist.

Brought up, as he says, in the British establishment, in a prosperous part of the Home Counties, his father an army officer, his grandfather a war hero. Privately educated at one of our better public schools and Christ’s College Cambridge, his early writing career followed a predictable path as a political correspondent for such bastions of the Tory establishment as the Daily Mail, the Telegraph and the Spectator.

Oborne became increasingly uneasy about the demonisation of Muslims that followed the terrorist attacks in 2001

Somewhere along the line, however, he began to notice that the world was not quite as he had been brought up to believe and, therefore, to stray off message.

I sympathise.

Although not quite from the same drawer as Oborne, I, too, was born into a middle-class, Home Counties family and privately educated. My road to Damascus (probably the appropriate term considering the subject we are about to discuss) came earlier than his.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Even in the isolation of my Catholic boarding school, with only The Times and the Daily Telegraph to rely upon for information about the outside world, I managed to work out that there was something wrong with the official version of the war in Vietnam and my outlook changed from that moment on.

Oborne’s "road to Damascus" came later in life. A deeply moral man, with a profound sense of right and wrong and a questioning intelligence, he became increasingly uneasy about the demonisation of Muslims that followed the terrorist attack on New York’s Twin Towers in 2001.

In 2015 he resigned his comfortable billet as chief political commentator of the Daily Telegraph and has since ploughed his own furrow.

The result is this magnificent work documenting relations between Islam and the West.

A magnificent work

The early chapters recount the history of relations between Muslims and three of the great imperial powers: the US, France and Britain. Until the mid-20th century contact between the US and the Islamic world had been limited to fighting off Barbary pirates and suppressing Moro tribesmen in the Philippines.

The first Muslims came to the US 400 years ago as slaves, and until the 9/11 attacks their influence on US politics and culture was marginal.

America first began to engage with the Arab world in the 1930s when, following the discovery of vast oil reserves, it supported the Arab tyrannies and the shah in Iran. The role of the CIA in the overthrow of Iran’s first elected government and decades of unconditional support for Israel placed it irrevocably on a collision course with much of the Arab world.

British and French engagement with the Muslim world stretched back much further to the days of their respective empires. In Britain, the post-colonial era resulted in relatively large-scale migration by Muslims to the UK where - by and large - they lived in relative harmony with the indigenous population.

The French, however, had to be prised out of their empire.

The vicious Algerian civil war resulted in large-scale migration to the motherland by former colonialists whose extreme-right views have poisoned the well of French politics ever since.

Native Algerians who served the colonial regime also fled to France in large numbers, resulting in the growth of a large, impoverished, resentful and resented Muslim underclass. The 9/11 terrorist attacks were the spark that lit the prairie fire.

The West's new enemy

The influential American political scientist, Samuel Huntington, had long predicted that the vacuum which followed the collapse of the USSR would be filled by a clash of civilisations, notably between Islam and the West.

The Christian right, neo-conservative think tanks and redundant cold war warriors rapidly took control of the narrative about Islam, often with tragic consequences

The rise of Al Qaeda and the attack on New York and the Pentagon appeared to be the fulfilment of that prophecy.

Oborne argues that it was nothing of the sort. "Not a single one of the world’s fifty Muslim-majority countries has declared war on the US. Nor have we seen an Islamic coalition forming."

He goes further: "Many credible analysts in the Arab world hold the US responsible for the conditions that allowed terror groups like Al Qaeda to flourish – and Islamic State to exist in the first place – when they invaded and occupied Iraq and destroyed state institutions. Huntington mattered very much. His thesis that the civilised world was fighting "radical Islam" provided the Western military-industrial complex with the idea of a global, systematic, multinational enemy. It has helped create wars and provoked hatred in the United States and among its allies across the globe."

One of the most interesting chapters documents how, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks in both the US and the UK, the usual suspects – the Christian right, neo-conservative think tanks and redundant cold war warriors - rapidly took control of the narrative about Islam and extremism, often with tragic consequences.

One small example: Tahir Alam, a highly motivated British citizen of Pakistani origin, who, as chairman of governors, played a leading part in turning round a failing secondary school in Birmingham.

He was denounced and disgraced on the basis of inaccurate and anonymous allegations about "Operation Trojan Horse", a non-existent plot by Muslim extremists to "Islamicise" local schools. Particularly depressing was the ease with which government agencies, politicians and the media fell for it.

The West, says Oborne, needs to rethink its relations with Islam. Recent western analysis has been beset by intellectual and moral error. "The intellectual error has been to think about Islam in terms of the Cold War…"

"The moral error has been to suppose that the West is engaged in an existential conflict with Islam (or Islamism), as it had been against the Soviet Union."

He goes on:"The strategy was wrong in itself. It also awarded a legitimacy to movements such as al Qaeda and Islamic State. These terror groups had always argued that Western support for democracy was a sham. Western policy since 9/11 has validated that al-Qaeda analysis. Both sides have a shared contempt for democracy, human rights, the rule of law and due process. In their different ways both accept the Marxist doctrine that the end justifies the means, up to and including barbaric methods like torture and civilian casualties."

When it comes to democracy, western governments speak with a forked tongue. Although their leaders regularly profess their love of free elections and human rights, they have all too often – as during the cold war – allied themselves with tyrants.

Egypt is only the most recent example.

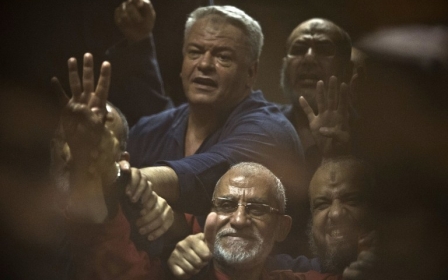

No sooner had the Muslim Brotherhood won power in 2012 in the nearest thing to a free election that Egypt has ever known than alarm bells began to ring. When, inevitably, the Egyptian military overthrew the elected government, imprisoned the president and began arresting, torturing and murdering its supporters, the West stayed silent.

On the contrary the military dictator, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, has been received with honour in western capitals. The flow of arms and aid continued. How do we suppose this looks to the average Egyptian listening to western leaders prattling on about democracy and freedom?

A great service

This is an impressive work, scrupulously documented and written with beautiful clarity.

There is, Oborne argues, no inherent reason for three of the great religions of the world – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – to be at war with each other. They all worship the same God as the Old Testament prophet Abraham.

If I have any quarrel with the author’s analysis, it is that he tends to imply that the blame of the present sad state of affairs can be laid almost entirely at the door of the West

All three religions originated in the Middle East and venerate many of the same historic holy sites. We have to start somewhere, of course, but given recent history, it will not be easy to put the genie back in the bottle.

If I have any quarrel with the author’s analysis it is that he tends to imply that the blame for the present sad state of affairs can be laid almost entirely at the door of the West. To be sure much of it can, but how can one explain the ferocious cycle of sectarian violence or the tit-for-tat slaughter in northern Nigeria? All the great religions contain the virus of extremism.

Nor do I quite buy the suggestion that the fault lies mainly or entirely with the West. To be sure much of it does, but there are aspects of Muslim culture that need to be challenged. The treatment of women and girls, for example.

And how did it come to pass that those who planted bombs in the London Underground or who murdered the MP David Amess were British citizens, born and bred in this country with access to all the advantages that life in a prosperous liberal democracy can confer?

I once knew a famous journalist who had reported from almost all the wars and battlefronts of the post-war era. "Every day," he said, "I get up and thank God that he never made me an expert on the Middle East."

Generally speaking, that has been my sentiment, too. Oborne has rendered a great service by going where other mainstream journalists and commentators fear – or perhaps can’t be bothered - to tread.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.