Why 'political Islam' can be a gateway to democracy

The post 9/11 "war on terror", which fuelled a dramatic upsurge in Islamophobia across the West through the stigmatisation of all Muslims as potential terrorists or "jihadist sympathisers", has now been dramatically expanded into a war not just against actual terrorism, but also "Islamism", "political Islam" and non-Muslims labelled as "Islamo-leftists".

In certain countries, especially France - which since the first 1989 "headscarves affair" has sadly become the West’s laboratory for Islamophobic experimentation - those witch hunts have even morphed into official state policies.

These are often replicated by other western countries. After France, Denmark announced that it was launching an “investigation” into the alleged spread of “Islamo-leftist” activism in its own universities.

By discouraging or even banning legitimate and positive forms of civic and political engagement, our governments risk encouraging the very phenomena they claim to want to combat

Justified by problematic “conveyor belt” theories of radicalisation and “gateway drug” concepts advanced by certain hyper-mediatised (and overrated) academics, and based on simplistic and broadly debunked notions of “Islamism” as the “antechamber” to violent armed jihadism, this type of demonisation now aims to censor, ban and criminalise everything presented as “political Islam” - even when it’s not.

Far from limiting itself to violent extremist action, this all-out enterprise brings together governments, mainstream media, think tanks and certain sectors of academia in a highly deleterious securitisation of Islam and Muslims, who are conceived as an existential threat to national security, and more generally, “western civilisation”. It proceeds via gross confusion among religious conservatism, fundamentalism, radicalisation, “political Islam”, Islamism, non-violent extremism, and jihadist terrorism (whether real or potential).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The consequence of that fallacious continuum among qualitatively different phenomena is that mere religious orthopraxy, such as an emphasis on prayer rituals or Islamic dress, is immediately perceived as the “gateway” to jihadism, and treated as such. But this only seems to apply to Muslims. Islamophobic double standards ensure that Jews, Christians and others remain untouched by such gross generalisations and false equations.

Systematic assault

More recently, this eradicationist approach has targeted peaceful civic engagement on the part of Muslims, even when it is carried out entirely within the democratic institutions and frameworks of our societies.

The exclusion of veiled mothers from school trips on the pretext that their hijabs would violate the “separation of church and state”, and the banning of anti-racist NGOs, such as the French Collective Against Islamophobia, on the grounds of it being an “Islamist” organisation, are only two recent examples of this systematic assault on the basic rights of Muslims.

As explained by journalist Myriam Francois, this expanding and worsening “problematisation of Islam” and Muslims stems from a refusal to extend civic rights and equal treatment to certain minorities: “Instead, an underlying and unresolved racism refuses to fully recognise Black and Arab French men and women as equals. Rooted in white supremacy and dressed up as ‘defence of the nation’, it is whitewashed nationalism with a socialist twist.”

Prominent philosopher Jacques Ranciere goes further, analysing this new war on Islamism as an attempt to “criminalise all social struggles and civic actions in favour of discriminated minorities and immigrant groups by presenting them as potential auxiliaries of jihadist terrorism”.

Such policies are not just gravely anti-democratic, but also profoundly counterproductive, since civic engagement in the life of one’s nation - including politics - is a well-known factor in both the inclusion of minorities and the pacification of frustrations, which may otherwise find outlets in more radical forms of engagement.

Research has amply demonstrated that civic participation, even when fuelled by a sense of religious duty to contribute to one’s society, far from representing the “threat” that some have dreamed up, is actually a powerful factor of integration, helping to consolidate one’s sense of belonging, place, citizenship and identification with the nation.

By discouraging or even banning legitimate and positive forms of civic and political engagement, our governments risk encouraging the very phenomena they claim to want to combat, such as “radicalisation” and “Islamist separatism”. By preventing Muslims from becoming political actors, governments can only make them feel excluded and unwanted, generating frustration, anger and disillusionment.

Radical differences

As rare voices have the courage to assert in today’s climate, rather than being banned or viewed with paranoid suspicion and fear, “political Islam” - including the critical varieties that might not fit well within the normative political cultures of the West - should be encouraged, engaged with, or at least tolerated.

After all, that is what democracies and free societies are supposed to be about, recognising that dissent and challenges to the existing order are not just legal and legitimate, but healthy. On the other hand, criminalising certain political Islamic movements is probably the worst course of action, as such discriminatory policies are precisely what groups such as the Islamic State (IS) hope for on the part of western societies, pushing more Muslims into their arms out of anger and frustration.

Fallacious presentations of “Islamism” as monolithic and universally toxic for democracy - its alleged antithesis - ignore the diversity of Islamist movements, the radical differences and irreconcilable divergences that often separate them, and the dramatic historical mutations of certain movements, such as the Muslim Brotherhood, Europe’s new bogeyman.

It thus bears repeating that if IS is indeed an Islamist organisation, so too is a democratic movement such as Tunisia’s Ennahda and its leader, Rached Ghannouchi. Yet, the gap between the two is so vast that they are indeed not just “different”, but irreconcilable - even if they are all “Islamists”.

The blissful ignorance among many segments of society of the ample research on Islamist movements, not to mention the diverse forms of “political Islam”, ensures that those terms simply mean “bad”, “barbaric” and “dangerous” - and that whoever is labelled as such can be targeted for elimination by state powers in the name of “democracy” and “defence of the nation”.

According to Jocelyne Cesari, one of the world’s top scholars on Islam, the false narrative that political Islam leads to violence and extremism ignores the fact that if Islamism can, under certain specific circumstances, be a gateway to radicalism, it can also "be a gateway to a more democratic and pluralist worldview”.

Ruptures and reforms

In her book Islamism in Power, Anne-Clementine Larroque has shown that once in power, Islamist parties or movements tend to moderate and even reform themselves, while establishing ruptures from more radical groups, especially jihadists, which are “the kiss of death”. This observed pattern invalidates the simplistic “political Islamism = armed jihadism” equation, or the gateway drug pseudo-theory that one leads to the other.

Other top experts on Islam, including John L Esposito, arguably the world’s leading scholar on the topic, have shown that the genuine search for social, economic and political justice is at the heart of the Islamist project - and that this “yearning” is one of the main characteristics shared by most parties and movements.

The AKP also pulverised the false cliche that 'with Islamists, it's one vote, one time', since Erdogan and the AKP have regularly submitted themselves to the rule of the ballot box

Several cases of Islamists in power show that if given the chance, they are perfectly willing to live by democratic rules. Ennahda in Tunisia, whose conduct could teach lessons in civic spirit and democratic behaviour to western parties, is by no means the only one, or the “exception that confirms the rule”, as the anti-Islamism hysteria would have us believe.

Before Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s autocratic turn after the July 2016 failed coup attempt and the subsequent massive purges, the ruling AKP was also - and could become again - a model of democratic behaviour. It brought into the country’s mainstream political life millions of Turks who had largely been excluded from it, while giving historically marginalised minorities, especially the Kurds, unprecedented rights and recognition.

The AKP also pulverised the false cliche that “with Islamists, it’s one vote, one time”, since Erdogan and the AKP have regularly submitted themselves to the rule of the ballot box, even at the cost of losing major elections.

Progressive Islamism

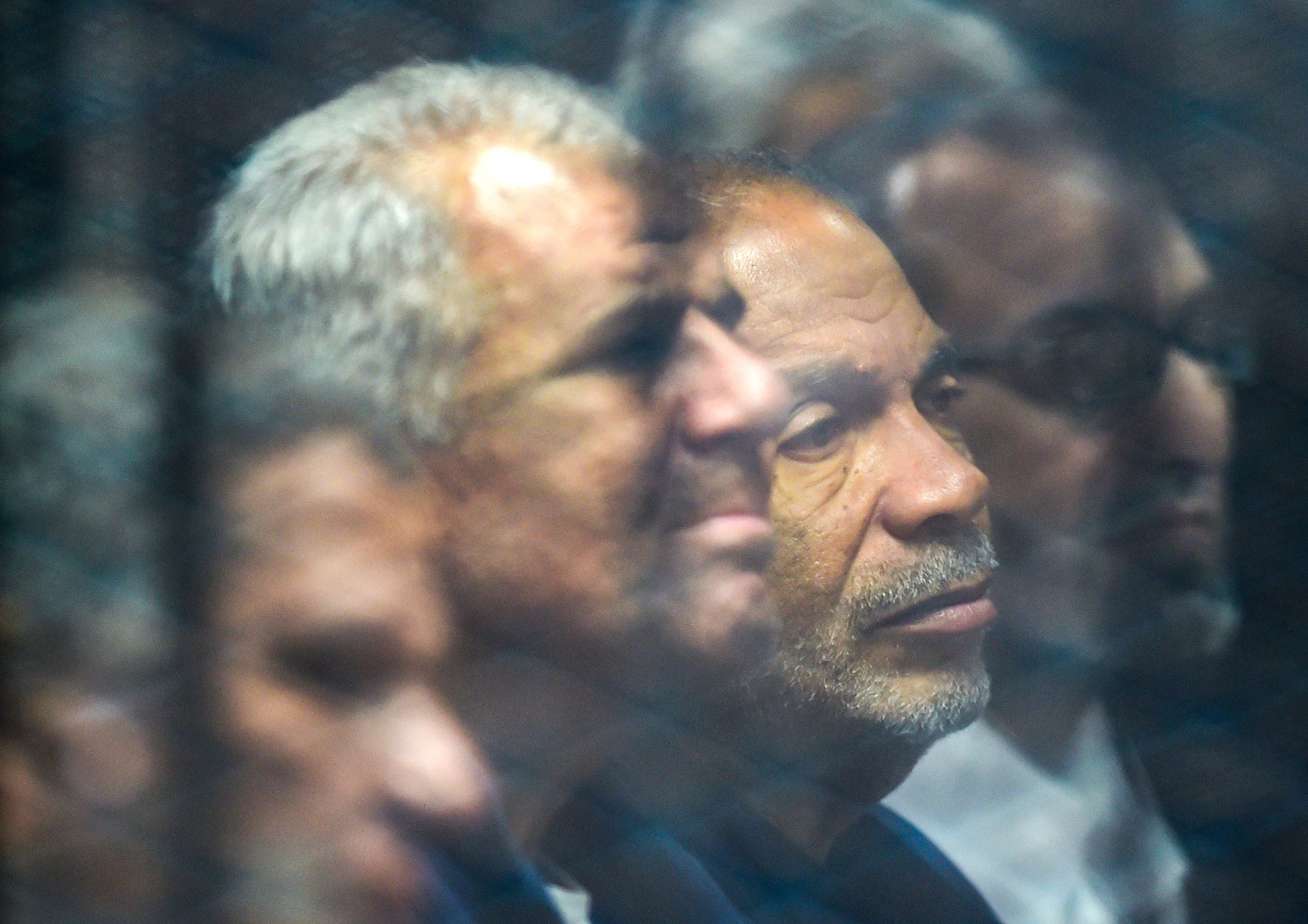

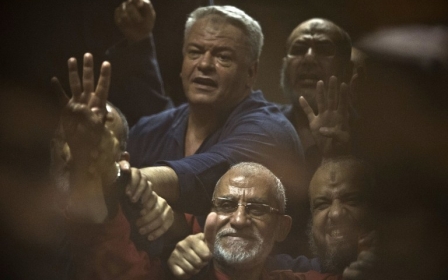

Another important example is Egypt under former President Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. Brief as their tenure might have been, given the premature interruption by the 2013 military coup of General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi - incidentally, one of the world’s worst totalitarian despots and proven mass murderers, who the US and EU support unconditionally while blaming “Islamists” for not being democratic enough - the Muslim Brotherhood’s rule was characterised by a substantial and qualitative expansion of democracy.

Using the Polity IV Index, one of the main political science tools to measure autocracy, democracy and their fluctuations, researchers Shadi Hamid and Meredith Wheeler demonstrated that under Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt had indeed started its democratic transition. Though far from perfect, given the impossible situation, Egypt became in a short period of time far more democratic than it had been under previous, non-Islamist (and even anti-Islamist) regimes. It was also infinitely more democratic and hopeful than under the current regime.

The blanket and crude vilification of “Islamism” and political Islam also ignores the existence of democratic Islamist trends, such as progressive Islamism - though ignorance may make that expression sound like an oxymoron.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.