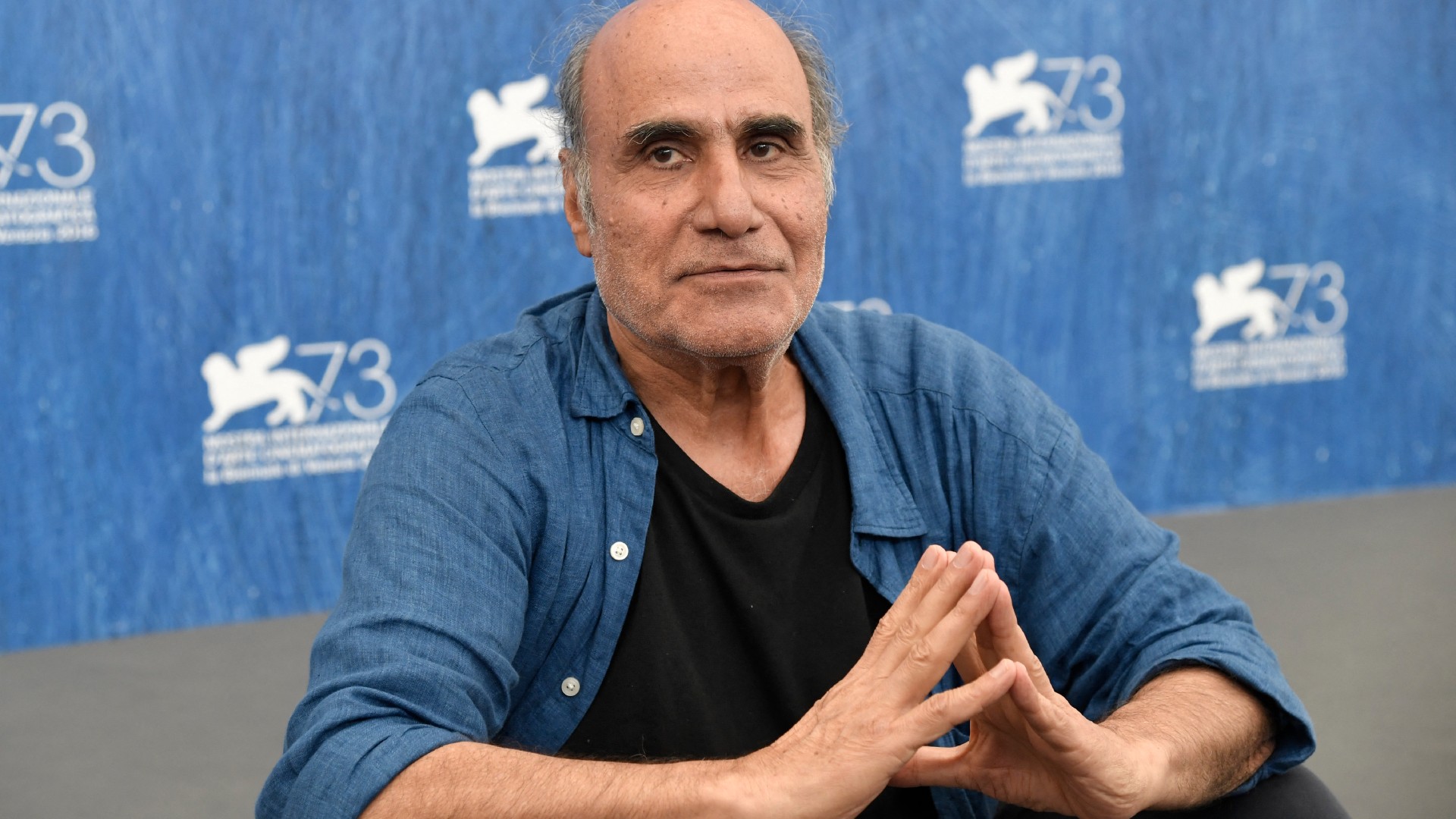

Mohsen Makhmalbaf: The precarious fate of a filmmaker in exile

I met the celebrated Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf during the Locarno Film Festival in August 1996.

I had seen a few of his films by then and was vaguely familiar with his fame and career. But after that encounter, I was so mesmerised by his works and persona that by the following summer I travelled to Tehran after an absence of some 20 years to spend time with him and his family.

What happens to the 'art world' of an artist when the world that had generated and sustained their creative urges is radically altered?

I researched the roots and fruits of his cinema on the ground and, about a decade later, I published a book on his extraordinary character and films: Makhmalbaf at Large: The Making of a Rebel Filmmaker (2008).

Today, if someone were to write a book on Makhmalbaf - and he richly deserves many more books on his illustrious career as a filmmaker - that person would have to go to London or Paris where he and his family are primarily based. There is no blaming Makhmalbaf, or any other artist who could not take the indignities of living under a tyrannical regime, for leaving with his family.

But what happens to the "art world" of an artist when the world that had generated and sustained their creative urges is radically altered?

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Artists without borders?

Makhmalbaf is not the first, nor the last, nor the only Iranian or any other artist, who has left their homeland. Among his own contemporaries, Sohrab Shahid-Saless and Amir Naderi have also left their homeland never to return, and resumed careers outside of Iran.

Many other Iranian notables, including poets and novelists, have settled in Europe or the US. In their later careers, however, they have managed to create an aesthetic rendezvous between their national and post-national art world. This crucial factor remains precarious in the case of Makhmalbaf.

To be sure, there is nothing wrong with getting to know a filmmaker somewhere far away from their homeland. There is, in fact, a certain advantage to that prospect.

I met Makhmalbaf in Locarno while he was screening one of his masterpieces, A Moment of Innocence (1996), as the Locarno Film Festival that year celebrated the pre-eminent Egyptian filmmaker, the late Youssef Chahine, with a major retrospective.

Two other Egyptian filmmakers were in Locarno that year too: Yousry Nasrallah and Osama Fawzy, as was the eminent documentary filmmaker Mohammed Shebl (who suddenly passed away the following October) - and, much to my surprise and delight, the legendary Egyptian actress Hind Rostom.

Such occasions outside Iran or Egypt or any other particular country give filmmakers and those who care about their artwork chances to meet and understand each other’s work better.

That year in Locarno I assumed an ambassadorial role and invited Makhmalbaf, Chahine and other Egyptian filmmakers to dinner. They scarcely knew each other’s work. The Egyptian most knowledgeable about Iranian cinema was the legendary film critic Samir Farid (1943-2017) who was also present at the festival that year. We had a casual debate about the new directions in Iranian and Egyptian cinema.

The rise and fall of Makhmalbaf

The spectacular rise and the eventual fading of Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s powerful cinema from the horizons of his homeland is a curious lesson on the precarity of national cinema.

Makhmalbaf emerged like thunder, a flash of bright light out of the blue catching almost everyone by surprise. He was an active revolutionary figure in his youth, and was captured, tortured, and imprisoned for four years before the 1979 revolution.

He came out of prison and devoted himself to the artistic aspects of the revolution he endorsed and soon began writing fiction and making films in the spirit of the new Islamist age.

Soon the tragic death of his young wife, who was active in his career, turned him into a devoted father. He married his sister-in-law, Marziyeh Meshkini, a gifted filmmaker in her own right, and the two of them raised and educated his three children as young filmmakers. His elder daughter, Samira Makhmalbaf, was the youngest filmmaker who at the age of 17 premiered her first film, The Apple (1998), at Cannes. I flew to Cannes that year and on many other occasions to celebrate with them.

Makhmalbaf’s rise to fame was on the bedrock of a new revolutionary environment and its ideological battlefields with the ancient regime. His earliest films, such as Repentance (1983), Two Sightless Eyes (1984), and Boycott (1986) were all deeply committed to the spirit of the Islamist revolution.

But with films like The Cyclist (1987), The Peddler (1987), and Marriage of the Blessed (1989), he parted ways with the ruling regime and eventually found his independent vision and provocative take on the art and craft of filmmaking. Through his film Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1992) he wrote a love letter to the history of Iranian cinema and sought to be a bona fide member of it.

Beginning with Time of Love (1991) Makhmalbaf had moved outside Iran for more appealing locations in Turkey, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and eventually, Afghanistan, where he finally made his widely celebrated film Kandahar (2001), which became an iconic antidote to the war propaganda of the Bush administration during the US invasion of Afghanistan.

Makhmalbaf arguably made his best films while he lived in Iran, and then his equally compelling output was evident when he turned Afghanistan into a metaphor for the rest of the world. His Afghan Alphabet (2002) about the fate of children was commissioned by Unicef, but when ready Unicef refused to endorse it because of its abusive handling of the veiling habits of young Afghan girls.

Makhmalbaf arguably made his best films while he lived in Iran, and when he turned Afghanistan into a metaphor for the rest of the world

Makhmalbaf’s sojourns into film festivals and his political opposition to the ruling government in his homeland eventually took him out of the country.

The films he has made outside of Iran are neither Iranian nor Turkish nor Tajik nor Italian - if we were still to think of aesthetics and the politics of national cinema.

Aspects of his most potent visual vocabulary are still at work but he has lost, perhaps forever, the moral thrust and visionary force of his cinema that he carried with his camera from Iran to Afghanistan, and seems to have left it there.

Many filmmakers left their homeland and continued to make films outside Iran. Some sustained their cinematic signatures, while others could not and were swept away. Makhmalbaf did manage to sustain his signature but lost the soul of his cinema when the idea of his nation disappeared from his cinematic horizon - or else became a mere metaphor.

Travel to Israel

Makhmalbaf could have continued with that paradox until 2013. Then, with a callous disregard for the global BDS movement in solidarity with Palestinians, he travelled to Israel and joined the Jerusalem Film Festival.

I was in Milan attending a festival of Palestinian art and culture when the legendary Palestinian filmmaker Michel Khleifi, who was there too, told me with incredulity that he had just heard Makhmalbaf had gone to Israel.

I was deeply saddened, embarrassed, and baffled by the news.

Makhmalbaf was fully aware of my thoughts and actions and millions like me in regards to the Palestinian cause and always compared his own commitment to Afghanistan with mine to Palestine. So this could not have been out of ignorance - nor was it out of malice.

It was out of blind hatred of the ruling regime in Iran and a public thumbing of his nose at it. He evidently could not care less what his act meant for the rest of the world.

The visit turned out to be a calamitous turn for his name and reputation as it was for Iranian novelist Jalal Al-e Ahmad (1923-1969) decades earlier when he too could not resist the power of a free first-class ticket for him and his wife. Al-e Ahmad though had the decency soon to repent the stupidity of his act and seek publicly to correct his misjudgment.

Makhmalbaf to this day continues to defend his visit to Israel.

With his visit to a military outpost garrison state built on the broken back of an entire nation, Makhmalbaf lost the soul of his cinema, the moral mystic and the bold fabric of his vision he had cultivated with ease over a long career.

He began his career with a mistake (joining the Islamist cause) and he ended with a mistake (joining the Zionist cause), but in between, he produced some of the boldest and most brilliant films of modern Iranian cinema.

Postnational cinema

After his Israeli debacle, Makhmalbaf continued to make films and some even good films, The President (2014) and Marghe and her Mother (2019).

It is not fair or right to take his misbegotten trip to Israel as an indication of his entire career, which is still fortunately unfolding. But when push came to shove he put his career and that of his family over the just cause of a historically violated people, and that fact casts an entirely darker shade on his character and cinema.

The true measure of visionary filmmakers who put their nose to the grinder and do not waver in or out of their homeland was established by Amir Naderi, who did much of his glorious work inside Iran. When the country had no more to offer him he left for New York and resumed his work closely linked to his visionary filmmaking.

For me and millions of his other fans something precious was forever lost when he turned his back on the Palestinian cause and lent his name to a brutal settler colony

Naderi never wavered, neither praised nor condemned the Islamic Republic, and stayed away from Israel (though he did not say anything public on behalf of Palestinians either). His glorious cinema, as he once told me, has something to teach us beyond all passing politics.

In Naderi’s mature and still unfolding work, or that of Abbas Kiarostami or Bahram Beiza’i, the prospects of a postnational cinema sustains the best and overcomes the worst elements of a still poignant idea of a national cinema.

Makhmalbaf meanwhile continues to make films, some even good films, and he is happily welcomed in film festivals around the world.

But I, for one, have lost all but a memory of the love and affection I once so lavishly had for his pre-Israeli cinema.

I am confident his work still sparkles with his extraordinary gifts as an artist, but for me and millions of his other fans something precious was forever lost when he lent his name to a brutal settler colony.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.