What contemporary Iranian art can tell us about the world

No national art is just national art. It is a mirror taken to the world to face itself.

Throughout the 19th and much of the 20th centuries, western European and North American modern and contemporary art very much defined what “art” meant around the globe.

Throughout the 19th and much of the 20th centuries, western European and North American modern and contemporary art very much defined what 'art' meant around the globe

The rest of the world was just that - the “rest of the world” - and, as such, had to measure itself up against the yardstick of western art.

The imperial hubris and colonial conquests of this were channelled into their art and the world had to see itself in that mirror.

Art meant western art - the rest was aberration or commentary.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Orientalism, impressionism, post-impressionism, abstractionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Vorticism, Dadaism, surrealism and all similar movements in modern art were without a single exception formed mostly on the Euro-American axis of artistic creativity.

Eventually, Asian, African, Latin American and Russian artworks began to find their way into global consciousness and art festivals and biennales thought of themselves as ridiculously provincial if they did not pay closer attention to art scenes around the globe.

Soon, Venice, Documenta, the Whitney, Manifesta, Gwangju, Sao Paulo, Sharjah, Istanbul and countless other biennales began to replace and overshadow conservative museum sites in US and European cities, which now had to compete for attention with more serious and bolder curators around the globe.

Exciting and provocative

From Latin America, iconic muralists such as Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Jose Clemente Orozco revolutionised the conception of art by staging a spectacular vision of public art with a powerful political purpose.

Later on from Africa, Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu, Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui, Kenyan photographer Thandiwe Muriu, South African artist William Kentridge, Congolese painter Cheri Samba, Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj, Malian portrait photographer Malick Sidibe and Cameroonian artist Enfant Precoce put their continent on the map of contemporary art.

Not just the politics but the aesthetics, not just the message but the mediums of contemporary art began to be recast in far more exciting and provocative ways.

From the Arab world, artists such as Inji Efflatoun from Egypt, Ibrahim el-Salahi from Sudan, Dia al-Azzawi from Iraq, Palestinian artist Emily Jacir, Iranian artists like Charles Hossein Zenderoudi, Parviz Tanavoli, Parviz Kalantari and Aydin Aghdashloo, or Shahzia Sikander from Pakistan further complicated the global conception of art as we experience it today.

Iran and the world

A recent exhibition at the Asia Society in New York, “Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet: Contemporary Persians - the Mohammed Afkhami Collection”, was an unexpected opportunity precisely to revisit these seminal issues.

In this exhibition, works by more than 20 Iranian artists were collected and caringly curated by the leading scholar in the field, Fereshteh Daftari.

All of the works were in communion and critical conversation with their world and its race, gender, sectarian and political cleavages. Engaged with the fate of their homeland, these artists were equally at home in the world.

The exhibition was moderately well-received and several critical appreciations were written about it. The exhibition has been to multiple sites since 2017, when it was first at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada, and then at the Museum of Fine Arts, in Houston, in the US. It is also accompanied by an edited volume with the same title, edited by Daftari.

At the centre of the artworks collected here are the artists themselves, sometimes literally, gazing back at their beholders, demanding and exacting attention, as perhaps best evident in the work of the photographer Shadi Ghadirian - where we see the artist as both the subject and the object, the vision and the visible, of their own artwork.

Imperial framing

In this travelling exhibition, we have older artists such as Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Abbas Kiarostami and Shirin Neshat - as well as younger artists such as Afruz Amighi, Alireza Dayani or Shadi Ghadirian.

Some have passed away, others have just entered the scene; some live in Iran, others in Europe, the US or Canada. Only one lives in Dubai, Rokni Haerizadeh - no one in Latin America, the rest of Asia or Africa.

The collector himself is also evidently based in Dubai. It is basically an Iran-Europe-US-Canada axis - with the Arab mega city-state of Dubai thrown in - or, in short, what in the political parlance of the time is called “Iran and the West”.

Almost all these artists are deeply rooted in the classical and contemporary Iranian culture and yet communicative with this chimeric construct called “the West".

The artworks are deeply influenced by the political turmoil in Iran and its immediate environment - even when, as in the case of Shiva Ahmadi’s video animation Lotus, the central figure sits on a lotus flower in the familiar pose of the Buddha, before the piece evolves into issues of domestic tyranny.

Absent, however, is any indication of the global imperial framing of the works of art, of the politics of representation, the aesthetics of reception or the anxieties of displaced artworlds.

Iran, Persia, cat, caviar, California

The project has offered the curator a chance to make a strong and convincing argument about the centrality of Iranian political turmoil in its representative aesthetic imaginations.

“What unites the disparate works into a coherent theme,” the curator argues, “is the artists' coping mechanisms, which consist of subversive critique, quiet rebellion, humour, mysticism and poetry.”

But all is not subversion, rebellion or even humour. In addition, we also have fearful obsequiousness (we might even consider it cowardice) in the face of American power and hegemony. The phrase “Contemporary Persians” in the title of the exhibition alludes to something quite unsettling.

It refers much less to a “strategy of survival” than the patent attempt of post-revolutionary Iranian immigrants or first-generation Iranian-Americans, as they have dubbed themselves, to assimilate into the dominant bullying power of the racist ideologies that finally surfaced fully during the Trump presidency.

The phrase originated earlier than the 2000s, as the curator believes. In fact, it started almost a quarter of a century before then, soon after the Iran hostage crisis of 1979-1981, when a particular brand of Iranian immigrant (very much akin to anti-Castro Cubans) dissociated themselves from the ferocious fate of their homeland.

They found a new exotic niche for themselves in the vicinity of Persian cats, Persian caviar and Persian carpets, as they all gathered in certain opulent corners of California.

This is the moment when Iran became “Persia” and the Persian language became “Farsi” - all as strategies of a new generation of immigrants disowning the troubled fate of their homeland and endearing themselves to the wrong side of American identity politics.

Fierce and fearless vision

To be sure, the word “Persian” and “Persianate” are perfectly legitimate terms in the context of the long Iranian and south and central Asian history, and Persian literature. But its appropriation by immigrant Iranians after the 1979 revolution has a whole different genealogy.

The curatorial yielding to this phrase and post-dating it to a quarter of a century after it actually began is a mixed metaphor, for it both erases that history of deliberately distorting one’s identity to appease the dominant white supremacy and yet turns it into a paradoxical moment in not Iranian, but American art.

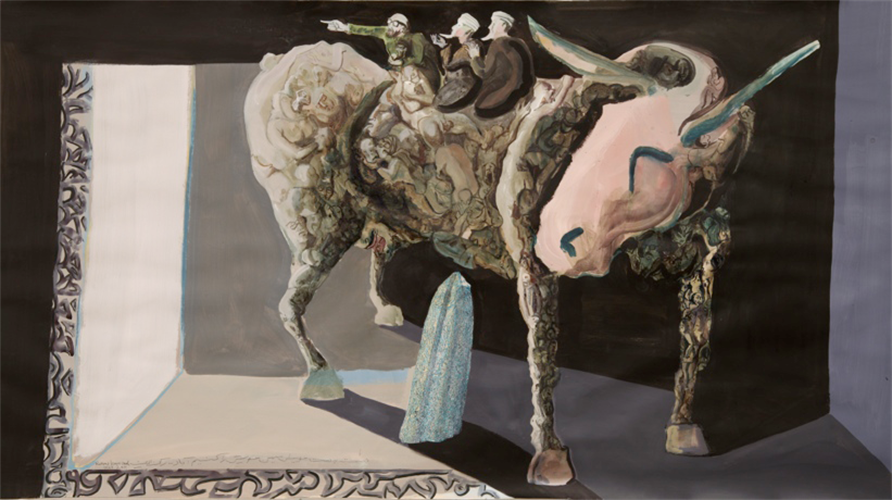

Shirin Neshat’s sudden rise to fame in the 1980s (carefully engineered by her gallery in New York) lasted for about two decades, eventually fading away and yielding to the superior work of artists such as Nicky Nodjoumi.

His steady hand and fierce and fearless vision - just like those of his peers Manoucher Yektai, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Siah Armajani and Ardeshir Mohassess - refused to cater to the Orientalist fantasies of their American and European spectators and persisted until they taught them a new way of seeing, being and imagining.

A few seminal artists wedded their revolutionary Iranian careers to the equally provocative American period: Nodjoumi and Mohassess, echoed in the abstract art of Yektai and public art of Armajani, are paramount examples of this art.

It is in this sense that artists like Yektai, Farmanfarmaian, Nodjoumi and Armajani began to cut through Orientalist fantasies and carved a powerful vista onto a new idea of American art that was equally evident in the work of filmmakers Amir Naderi and Ramin Bahrani.

There is a delicate line between calling yourself “Persian” or “in exile” for fear of a bad deal in the art market, and the superior sublimity of an artist who recasts and redefines an aesthetic culture rather than yielding to its exotic fantasies.

In their respective works, these superior artists did not yield to any Oriental ghetto for their artwork. They recast the whole contours of the art from the Global South into the heart of the Global North.

Understanding and curating that art requires a wholly different conception of our contemporary history.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.