Revolutionary art reminds us of the world we want to see

During the awful pandemic the world has endured over the past two years, it has been easy to forget what treasure and inspiration we can find on our doorstep. For me, the Department of Drawings and Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fifth Avenue, New York is one such extraordinary place.

The department houses more than one million drawings, prints and illustrated books, from the current day dating back to 1400; works which, because of their sensitivity to light and their sheer numbers, can only be on public display for a limited period.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

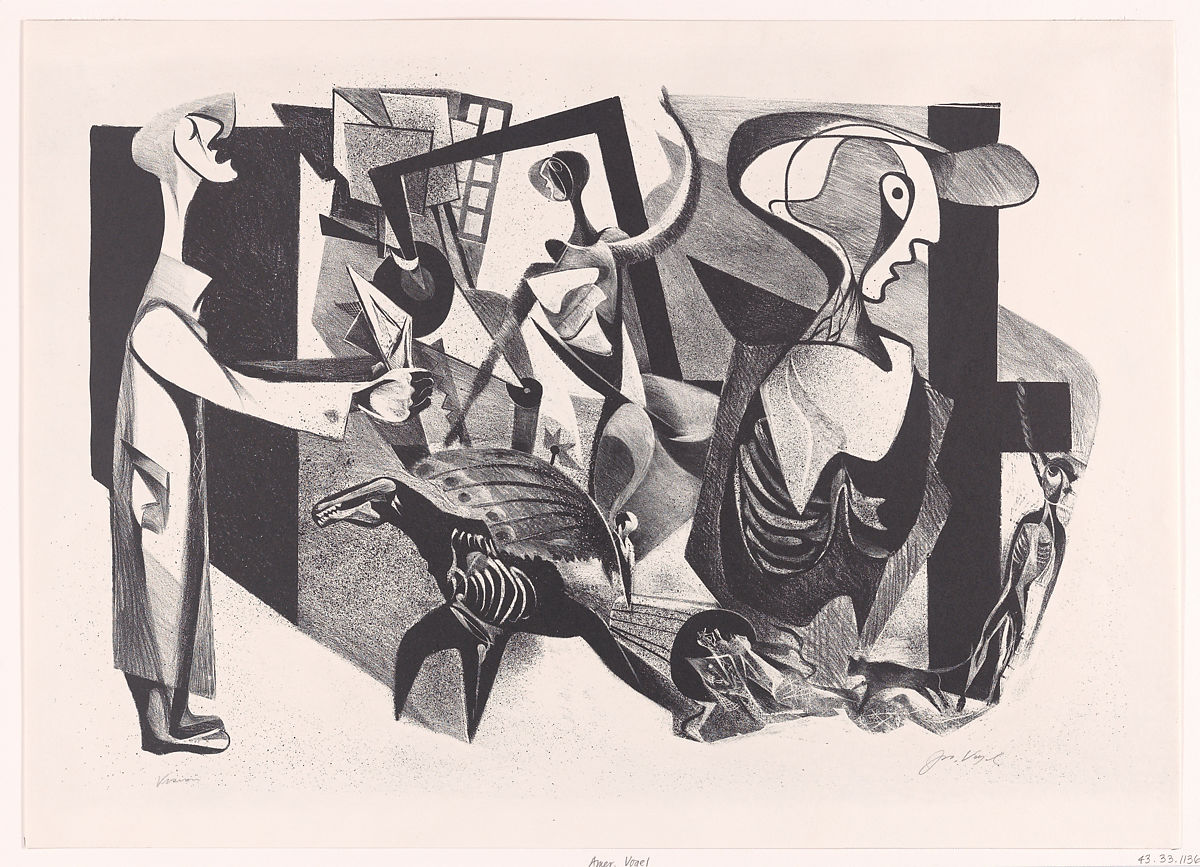

The Met is currently exhibiting a curated show from this collection, called Revolution, Resistance, and Activism, which runs until January 2022.

The exhibition showcases the crucial function of revolutionary artworks in key moments from the 18th century to the present day. We see how iconic moments in the American, French, Haitian, Mexican and Russian revolutions were depicted. Protest against slavery and other forms of racial, gender, and economic injustice are also represented.

Since the Iranian Revolution of 1978-79, I have been drawn to art inspired both by the revolution and the brutal Iran-Iraq War of 1980-88 which followed it. My colleague Peter Chelkowski and I wrote one of the earliest books on the subject - Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Last year, the New York Times published a major piece called "The 25 Most Influential Works of American Protest Art Since World War II". Among the powerful works of art were featured two Iranian artists, Nicky Nodjoumi and Ardeshir Mohassess - who had both long left Iran for a life in New York. Mohassess died in 2008. Last month, in New York, Nodjoumi held an exhibition of his most recent work.

Revolutionary dreams

The current exhibition at the Met demonstrates how artists have always used their work to bring attention to racial, gender and economic injustices. But these artworks do something even more important - they show us what those revolutionaries were dreaming of; what true justice might ultimately look like. The world has failed those dreams.

Someone in the heat of those revolutionary moments had the presence of the mind to collect and safeguard these artworks. Someone else had the political imagination to preserve them for posterity. Today, because of those known and unknown visionaries, we can look at these artworks and remember that, as Martin Luther King Jr said: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

They show us what those revolutionaries were dreaming of; what true justice might ultimately look like. The world has failed those dreams

I look at the Met's precious collections and wish there were similar archives of our contemporary uprisings, safely protected in museums in Cairo, Istanbul, Tehran, Delhi, Johannesburg, Mexico City and other major cities around the world.

What is the meaning of such collections for those who lived through the horror of Donald Trump and his followers, and what it exposed about this country?

For although he is no longer in office, this is still very much Trump’s America - with its reactionary, racist, white-supremacist legacy of the mass murder of Native Americans and the systematic slavery of African Americans. This is not something of the past, it is the prototype of American history repeated generation after generation to this day.

This is not something consigned to the past. This is American history repeated generation after generation to this day.

Power of protest

The fear of his return to run for president overwhelms any sense of relief that his attempt to claim this country in the image of his reactionary, racist interpretation of history was thwarted by Joe Biden. In the context of Trump’s America, the Met's exhibition and its artistic history of revolutionary pasts reminds us of the power and potential of protest. We must also remember that most decent Americans, of all colours, have not given up dreaming of a better future.

This battle - between the forces of racism, sexism, patriarchy, homophobia, misogyny and classist segments seeking to sustain their fragile domination and, on the other side, those fighting for a fairer, more inclusive, more equitable society - defines our age, not just in the US but globally. Viewed through this prism, the Met's exhibition could not be more timely.

Globally, revolutionary art needs archiving and protecting for posterity. The preservation of artworks depicting social uprisings against tyranny should not be the exclusive privilege of rich and powerful countries that can afford such endeavours. Poorer countries the world over have an urgent need for such archives, and their people must have access to them.

For artists such as Dia Azzawi (Iraq), Nicky Nodjoumi (Iran), Mona Hatoum (Palestine), Shahzia Sikander (Pakistan), or the late Inji Aflatoun (Egypt), such archives are crucial for our reading of their time and struggles. It would be wonderful if their work was as loved and celebrated as those of Jose Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros are in Mexico City.

Archives are not just a record of the past. They are recipes for the future.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.