Poverty, displacement and 300 storms: How 'climate violence' threatens Iraq

Iraq’s sky now rains dust and pollutants. The land between the Tigris and the Euphrates no longer gets enough rain to save the country from droughts, which have devastated local communities and agricultural supply chains, spurring a tide of migration.

The situation has deteriorated rapidly over the past two decades, with Turkey and Iran restricting the flow of water via dams and other infrastructure. Water has effectively been transformed into a political tool, while sand and dust storms are becoming more frequent across Iraq; it has been estimated that the country could experience 300 such storms a year by 2023.

This category of 'climate violence' poses a significant risk when combined with increasing poverty and unemployment

Today, as Iraq celebrates the centenary of its founding as a modern state, its ecosystem is on the verge of collapse. As water flows in rivers decline dramatically, Iraq is expected to become one of the world’s most water-stressed countries by 2040, with a forecasted rating of 4.6 out of 5, indicating extremely high stress. At the same time, Iraq is contributing to global warming, with the International Energy Agency reporting that the country accounts for around eight percent of world methane emissions.

Iraq’s environment ministry has acknowledged the ongoing climate crisis, which threatens to make Iraq unliveable over the next two decades due to excessive heat, drought, scarcity of water reserves, desertification and loss of biodiversity - all of which are wreaking havoc on food security chains.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

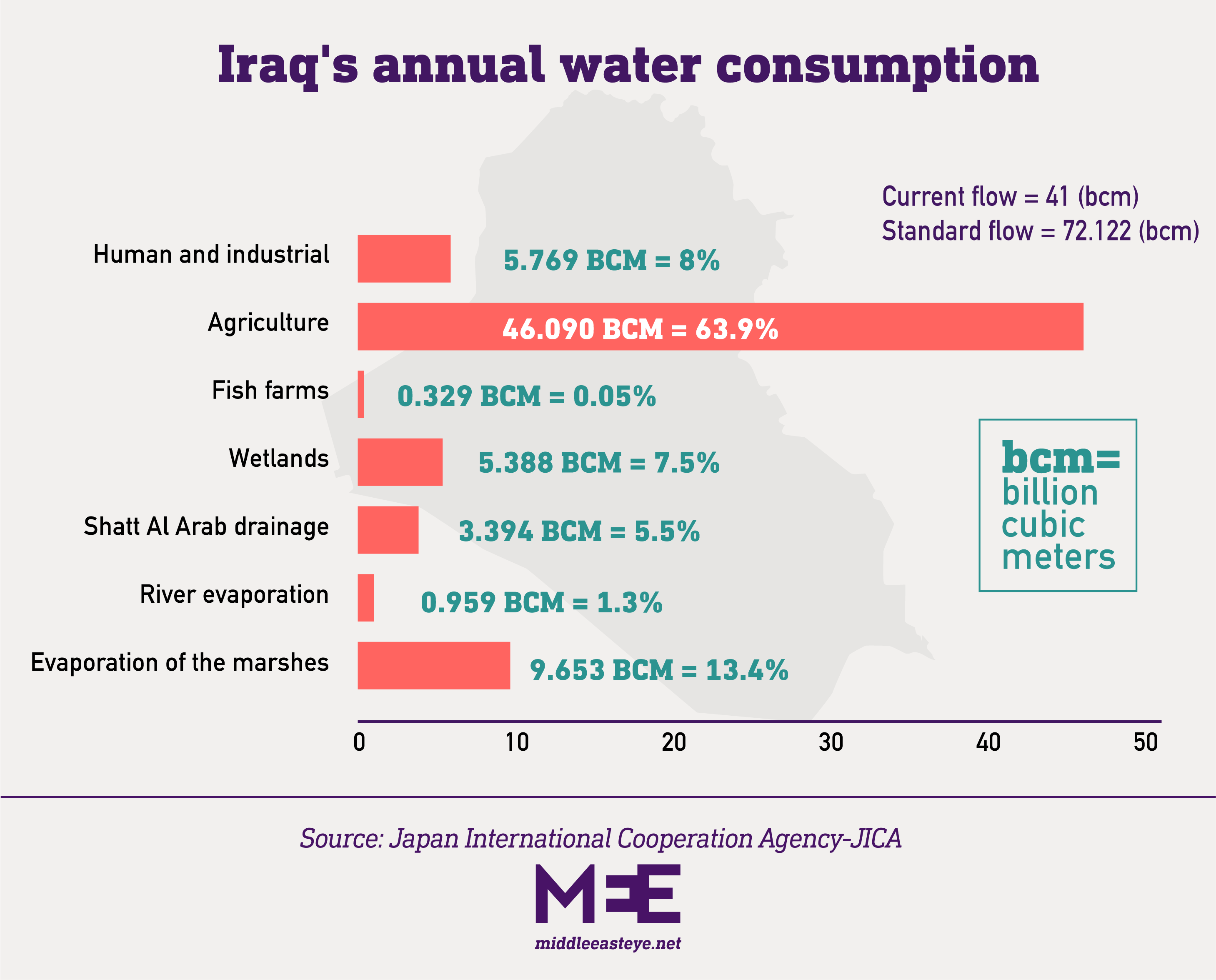

Iraq uses more than 63 percent of its water resources on agriculture, even when it often relies on imported food. According to the head of Iraq’s parliamentary agriculture and water committee, Salam al-Shammari: “Farming techniques in Iraq are rudimentary; therefore, we have a significant waste of water with a weak agricultural output.”

Rising temperatures

Agriculture contributes about four percent of Iraq’s GDP, and about 20 percent of the labour market depends on it. But amid climate change, water scarcity and increased armed conflict, agricultural production fell by about 40 percent between 2014 and 2018, according to the World Bank.

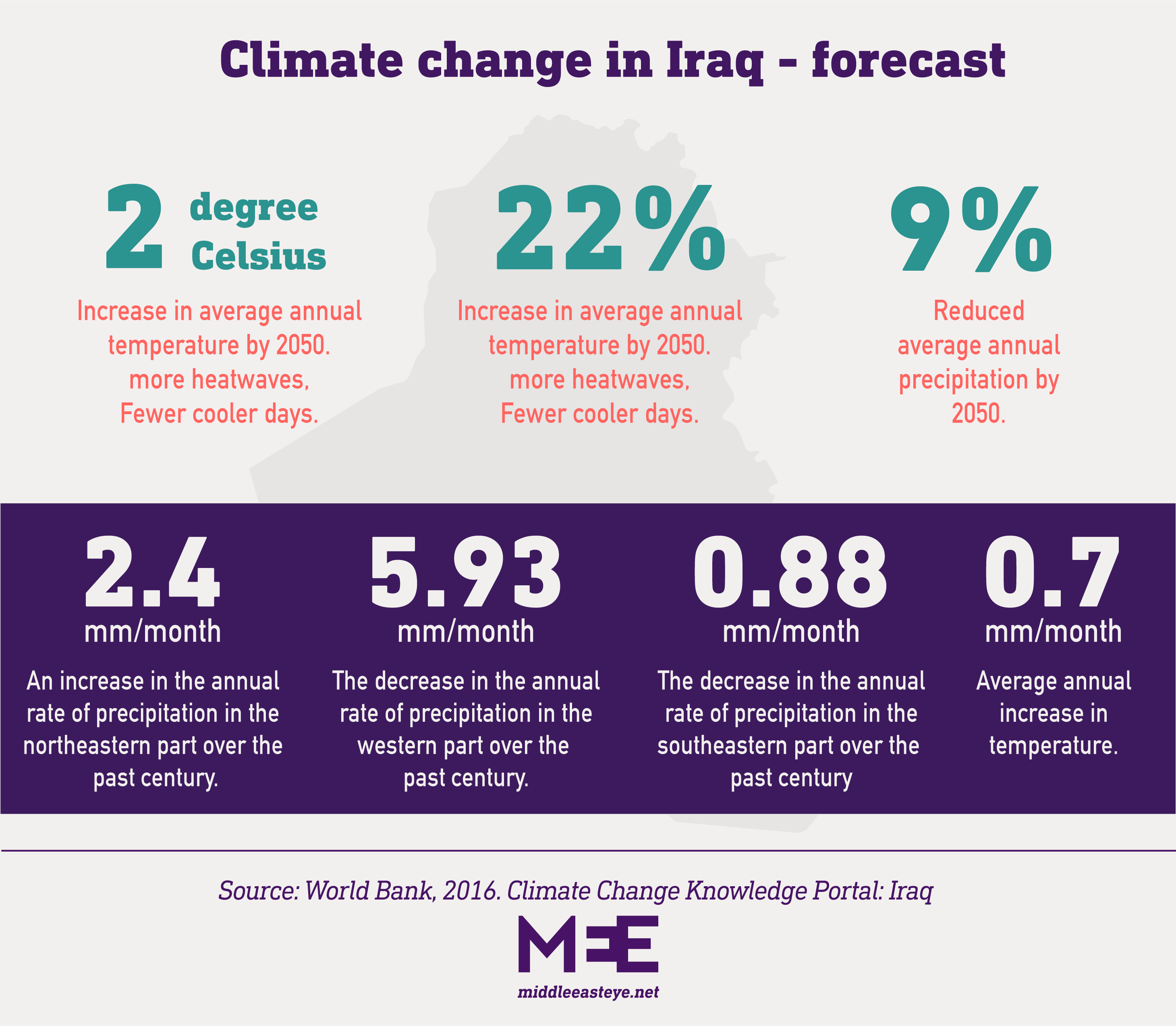

In addition to agricultural usage, Iraq loses around 15 percent of its water reserves annually to evaporation. Over the next few decades, the United Nations projects that temperatures in Iraq will rise by two degrees, exceeding the 1.5C threshold outlined in a worrying report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Excessive temperatures, often exceeding 50C in summer, have been decimating Iraq’s crops and livestock, destroying the ecological diversity of marshes and exacerbating shortages of safe drinking water. There are also thousands of fires every year.

Iraq fought to have its historic marshes added to the World Heritage List in 2016, perhaps seeing this as a way to safeguard water flows. But today, marsh dwellers are on the edge of peril. According to government estimates, buffalo numbers have dwindled to less than 200,000 from 1.2 million, as the salinity rate in various marshes has reached a “dangerous level of deadly pollution as a result of drought”, according to Jassim al-Asadi, a consultant with the Nature Iraq NGO.

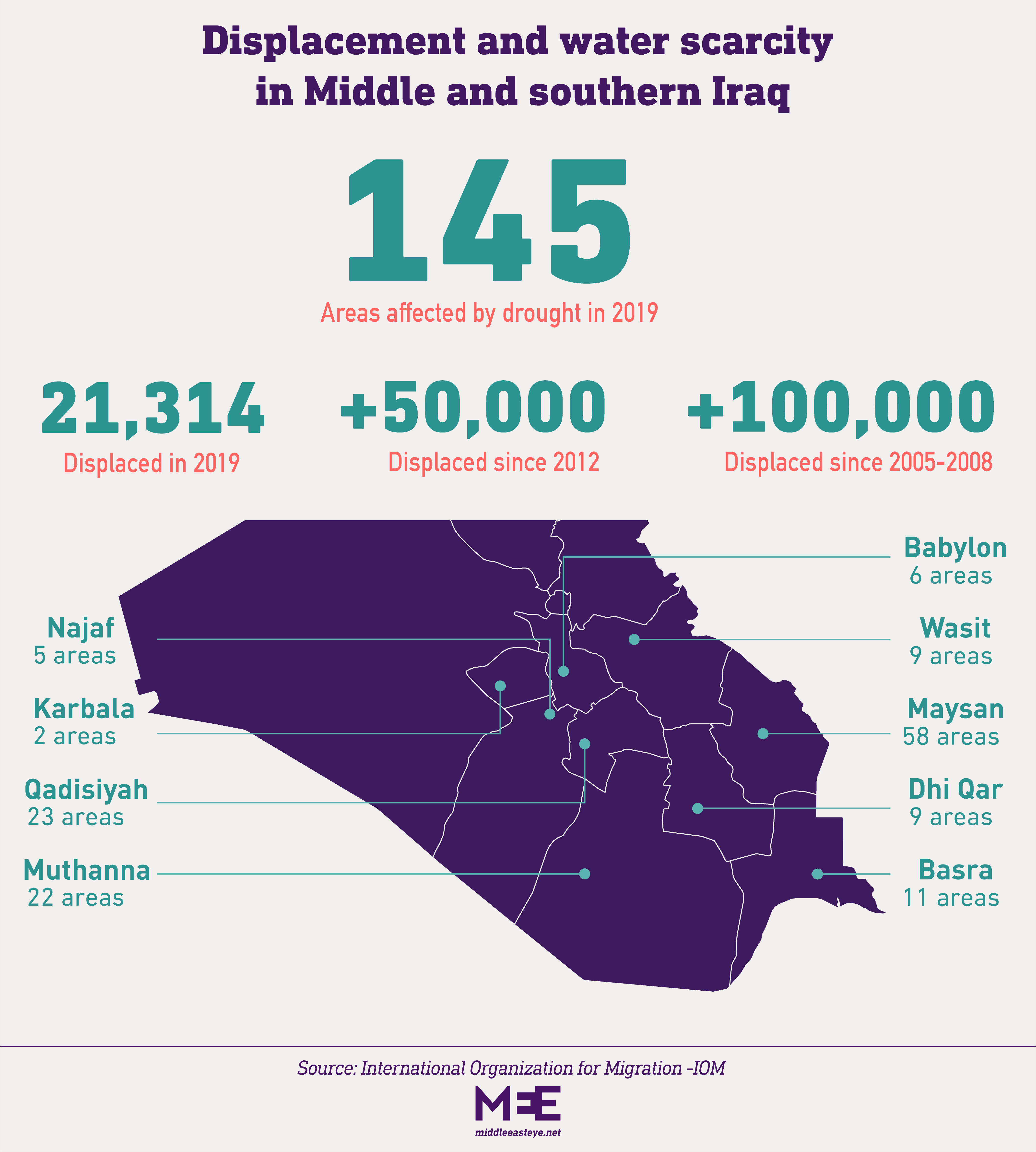

At the same time, the International Organization for Migration found in 2019 that 21,314 people from Iraq’s central and southern governorates had been displaced due to water scarcity, high salinity content in the water, or waterborne diseases. Several years earlier, in 2012, 20,000 people were displaced from agricultural communities due to drought. Families who have inhabited villages for decades are being forced to leave their ancestral lands.

“Livestock is entirely decimated, and there is not enough water, so why should farmers and fishermen remain in a dead land? Most of them have been displaced to the city, but there is no work in the city. Unemployment there is increasing day after day,” I was told by Karim Hattab, who heads the local farmers’ union in Maysan, southeastern Iraq, which has been severely affected by drought.

Weapon of war

The federal government has acknowledged that Iraq is part of a “double negative relationship between the environment and armed conflict … [which] has led to environmental pollution and serious damage that has impacts on the economy, society and the individual”.

Destruction of the local environment and water infrastructure has been wielded as a weapon of armed conflict in Iraq, particularly by Islamic State. Large quantities of water have been wasted in artificial floods; large agricultural areas have been destroyed; and valuable water reserves have been lost, forcing many to flee their homes.

This category of “climate violence” poses a significant risk when combined with increasing poverty and unemployment, population growth and a stalled economy. Yet, climate issues do not seem to be a priority for the Iraqi government. A draft law relating to national water resources management and conservation has been stalled since 2016. And Iraq was among the last countries to join the Paris climate agreement.

To remedy its environmental failures, Iraq recently launched a national strategy to combat climate change, in partnership with the UN Environment Programme. But the $2.5m in funding from the Green Climate Fund is nowhere near enough to address the scale of Iraq’s crisis.

Indeed, the Iraqi population is fighting an uphill battle to overcome severe climate change and drought, leaving millions of people facing an uncertain future in the months and years ahead.

Research for this article was done with the support of the Berlin-based the Candid Foundation

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.