Iraq war anniversary: How the US media covers up war crimes

I recently came across an article on the front page of The New York Times by a photojournalist reminiscing about his days at the height of the US-led invasion, destruction, and occupation of Iraq.

Something has happened over the last two decades since that war. Perhaps, most importantly, it is the combined consequences of the almost two years of the Covid-19 lockdown and the four-year plague of Donald Trump's presidency that I read the essay like a relic from a distant past that made little to no sense at all.

The active memory of that illegal, immoral, and deeply deceptive war has been so systematically erased in this country that this essay might as well have been a hieroglyphic tablet recently excavated from under an Egyptian pyramid.

"Twenty years ago this week," writes Moises Saman in this essay, "I witnessed the opening salvos of the United States invasion of Iraq from the rooftop of the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad. I was among the few foreign journalists not embedded with the American military who remained to cover the start of the war from the capital."

As the world last week marked the 20th anniversary of that singularly treacherous war, American media seemed to want to rush through a quick "remembrance", covering up the fact that they were central to launching it and then systematically sought to erase its deeply troubled memories.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Soul-searching journalism

The New York Times piece included some vivid pictures of the invasion and occupation of Iraq that commenced 20 years ago on 20 March 2003.

A little more than a month before that on 15 February, I was in New York, as one of the millions of people around the globe protesting the impending war on Iraq.

Saman uses this essay as an opportunity for some soul-searching about his profession: "I was driven almost entirely by the demands of the daily news, and by the need to prove myself. But events along the way began to complicate my role as a chronicler of the war, and I was forced to reassess my work as a photojournalist."

That bit of self-reflection falls far short in recognising the criminal role that the so-called paper of record and other mainstream outlets in the US played in facilitating and justifying this preposterous war.

Halfway through the piece we come across the name Abu Ghraib, the notorious prison where Saman himself was briefly incarcerated while Saddam Hussein was still in power.

From there on the author marks the changing narrative of the war as orchestrated by the US military and its American media platforms. His conclusion is marked by the scars of war on his meditative prose and politics: "Who has the power to narrate a conflict? Who determines the parameters of the frame? Which crimes or victims will be visible, and at the expense of what? I don't provide any answers. But I argue that it is essential to keep asking the questions."

One such deeply troubling question to ask by any American journalist is summed up in the ignoble name Judith Miller, a career opportunist who, as a journalist at The New York Times, played a key role in promoting the treacherous lie that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction - a deceitful untruth she had gleefully picked up from Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel who was a key cheerleader of the US-led invasion of Iraq.

Remembering Abu Ghraib

The single mention of Abu Ghraib triggered my memory in precisely the same way Saman questions: who gets to narrate the Iraq war or Afghan war or any other country at the receiving end of US and Israeli military thuggery - and by what authority and to what effect?

What this random piece in the Times and a few others that will appear over the next few weeks show is worse than collective amnesia. It is selective memorial tokenism and cliches to cover up and justify that deliberate forgetfulness.

Twenty years ago, US President George W Bush and his entire administration, with the active complacency of US media, including the most liberal, waged a devastating war against the sovereign state of Iraq without any provocation.

Saddam was not exactly God’s gift to humanity; he had waged foolhardy invasions of Iran and Kuwait with megalomaniac designs and active support of many Arab states, and a genocidal campaign against Iraq's Kurds. But the US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq was a callous repetition of those invasions on a more massive scale and had far-reaching implications for the geopolitics of the region.

Today, Putin is being formally charged by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity - and rightly so. But whatever Putin has done in Ukraine, Bush did even more so in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Putin, Bush, Tony Blair, Bashar al-Assad and a whole slew of other "world leaders" should be on the list of people the ICC investigates and condemns - if it is to have any meaningful legitimacy at all and not act as the propaganda tool of the European Union.

If there is a single word that captures the terror that the US perpetrated in Iraq and upon global moral conscience is precisely the word "Abu Ghraib": a notorious prison in which Saddam Hussein had kept and tortured his enemies and the US took over to once again violate every ounce of decency.

Members of the United States Army and the CIA photographed themselves in this prison committing sick and sadistic atrocities on the bodies of Iraqis they had imprisoned there - including physical and sexual abuse, torture, and rape.

To be sure, the illegal and immoral invasion and destruction of a whole country is not to be reduced to just one particularly notorious incident. But, there is something in that incident that has justly become emblematic of the whole moral depravity of US militarism that has always defined its politics.

Art of torture and memory

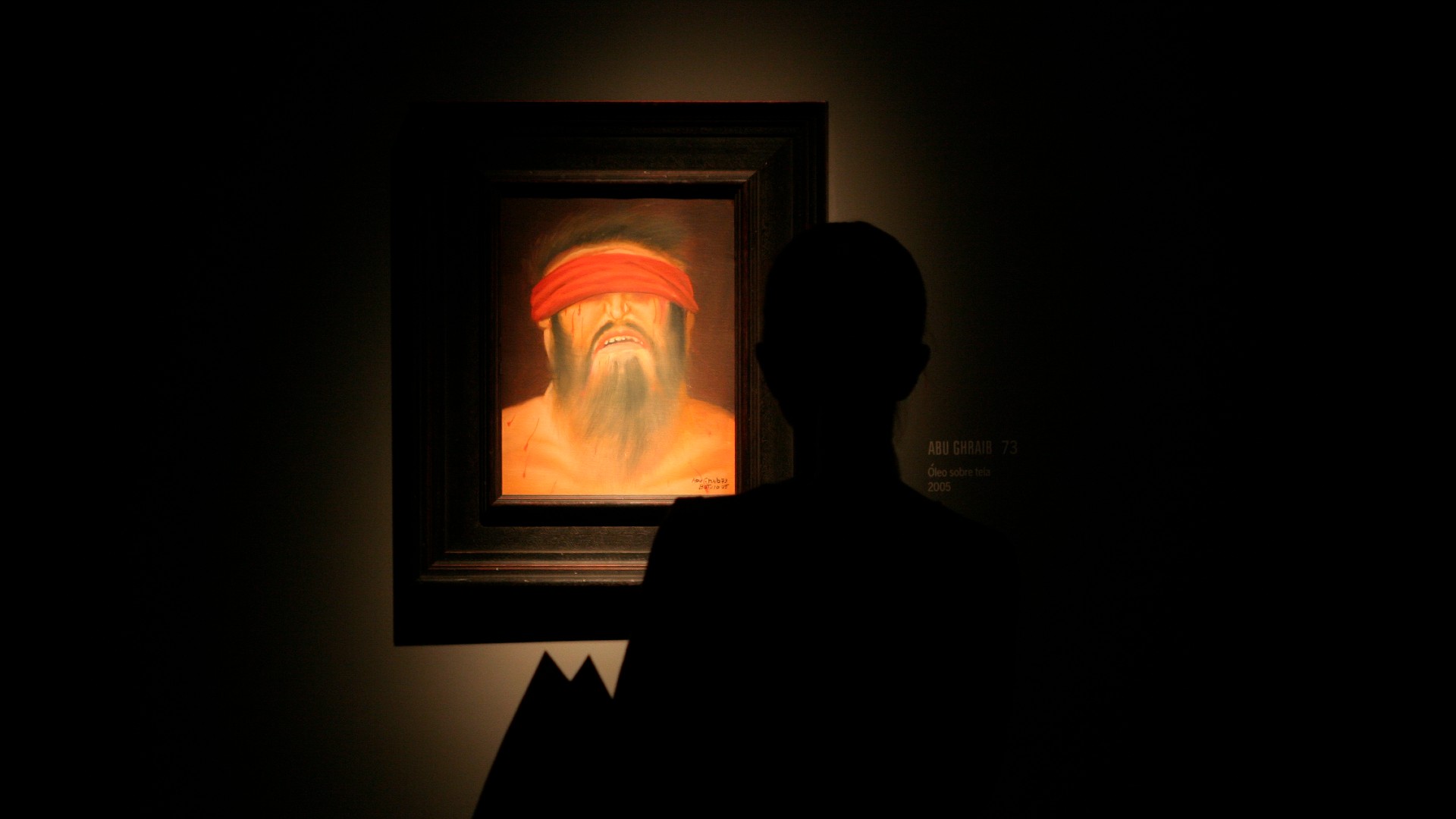

Ordinary language fails to convey that moral depravity, and thus soon major global artists began to look at the Abu Ghraib travesty more closely.

It was the Colombian figurative artist Fernando Botero who first put the visual evidence of the US's Abu Ghraib torture chambers to work as a world-renowned artist. I recall when I first heard of Botero’s Abu Ghraib series and saw them; I thought it was too soon to seek to aestheticise that terror.

I thought those ghastly snapshots (depicting the depth of human depravity) showing American imperialism in pure practice for the whole world to see should not be decipherable so quickly; theorised, archived, or in any other form normalised, and thus distanced from their repugnance to any decent human being.

These images were raw and brutal, the same way that American invasions and occupations of faraway lands have always been so. I then remembered the painting that Picasso had done of American atrocities in Korea, or German Nazi brutalities in Guernica, or what the Iraqi artist Dia Azzawi had done about Sabra and Shatila.

Be that as it may, there was something raw and brutish about those snapshots of American thugs in their military uniforms torturing and humiliating Iraqis who were in their custody that demanded to remain unreadable, precisely in their ghoulish nakedness.

These pictures to me were America, its entire history, the underbelly of its false claims to civilisation, to Christianity, to American culture in practice.

Botero, and any other artist who came near these naked pictures, created an aesthetic distance between what these snapshots showed and what the world thinks of the military logic of colonialism that had defined the history of European conquest of the Americas - and was now extended to the rest of the globe.

The pair of shoes that an Iraqi journalist threw at George W Bush summed up the feelings of millions of Iraqis

These pictures were reminiscent of the brutalities of the Conquistadors when they landed in the Americas, as best captured by the Spanish Dominican friar Bartolome de las Casas in his 1552 A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies.

As years went by other artists joined Botero. Susan Crile, a deeply cultivated American artist, did her version of Abu Ghraib. But the key issue was what Iraqi artists themselves made of these pictures. Last year, there was a report that a group of Iraqi artists had withdrawn from the Berlin Biennale in protest of an artwork depicting prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

But if Abu Ghraib symbolised the terror Americans perpetrated on Iraqis, the pair of shoes that the Iraqi journalist Muntadhar al-Zaidi threw at George W Bush during a 14 December 2008 press conference in Baghdad summed up the feelings of millions of Iraqis: "This is a farewell kiss from the Iraqi people, you dog," al-Zaidi said as he threw his first shoe towards Bush. That historic shoe later became the object of a work of art by Laith al-Amari, honouring the Iraqi journalist and the pride of Iraqi people.

What were those original snapshots for – what sort of moral depravity will first make someone do that, then stage the atrocities for fun and make a record of their deed? Once the prison guards snapped those shots, who were their audience - friends and families "back home"?

The final audience of those pictures was and remains posterity, to see in what particular ways this was an emblematic American war - a war Americans waged based on the false claims that Saddam had anything to do with 9/11 - a blatant act of state terrorism that targeted millions of innocent Iraqis.

Resorting to cliches about the "nature of war" will diminish the moral horror of the event. No doubt others have done similar atrocities: the Russians, the Chinese, the Myanmar military, etc. But it is only by mapping the details of one particular evil - in this case, an American evil - that we can better understand the universal terror of that evil.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.