How Mohammed bin Salman and Sisi abuse the Islamic concept of clemency

Ramadan is known as a generous month, but this year was especially generous to a couple of the most notorious murderers in the Arab world: Mohsen al-Sukkari and the killers of Jamal Khashoggi.

Sukkari is a former Egyptian state security officer turned hitman, hired by Egyptian billionaire real-estate tycoon Hisham Talaat Moustafa to murder the latter’s ex-lover, Lebanese singer Suzanne Tamim, in Dubai in 2008. Both Sukkari and Moustafa were originally sentenced to death, but upon appeal and retrial, their punishments were reduced to life in prison for Sukkari and 15 years for Moustafa.

President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, exercising his presidential powers, commuted Sukkari’s sentence to time served this past Eid al-Fitr. Moustafa, who was part of the inner circle of Egypt’s National Democratic Party at the time of the murder, received the same favour from Sisi three years earlier.

A bitter concession

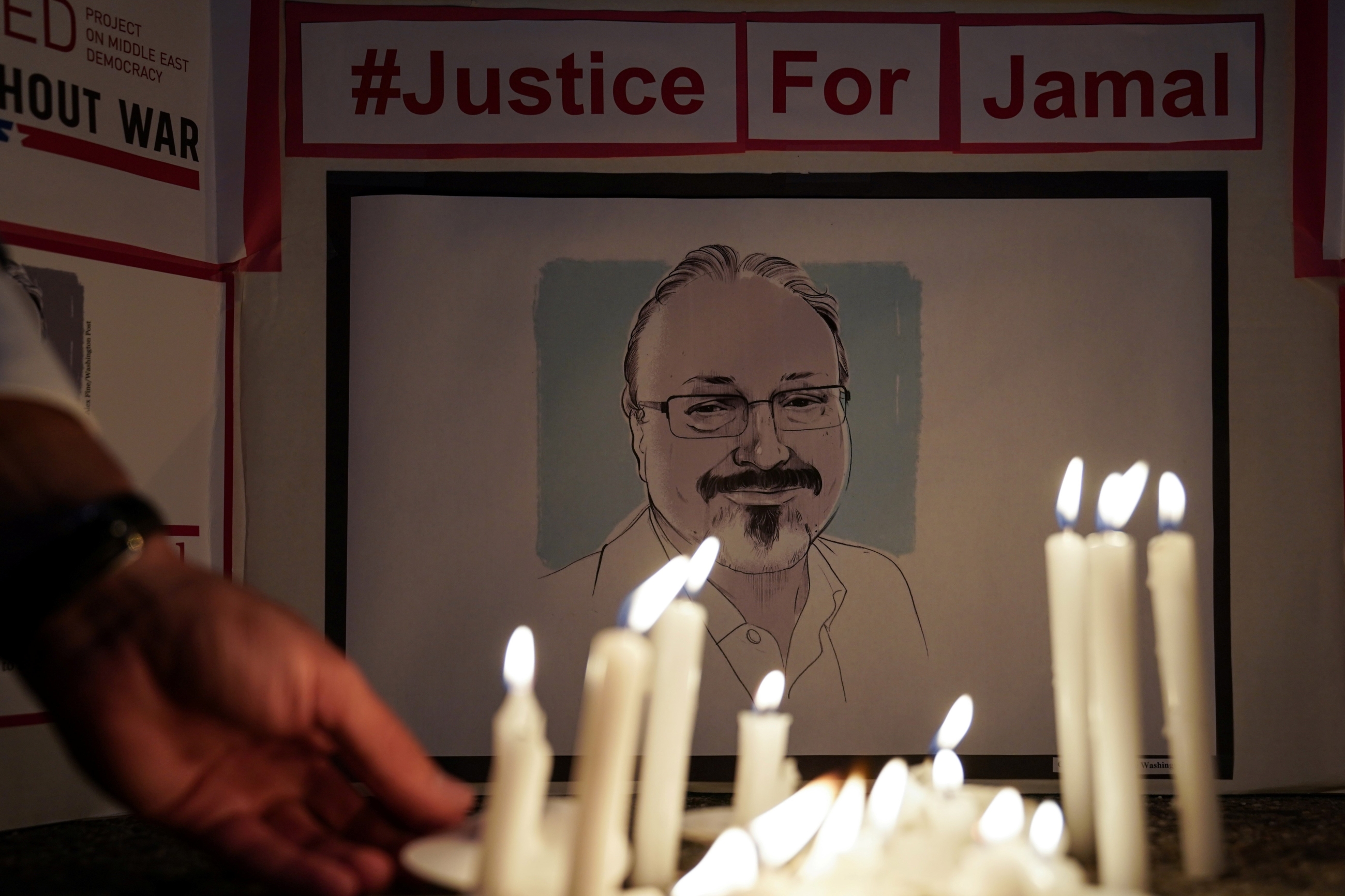

While many readers might have forgotten the death of Tamim, the brutal and brazen murder of Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018 received widespread international coverage and had far-reaching consequences.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Numerous intelligence agencies and international organisations, including the United Nations, linked Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman directly to the killing, even concluding that he ordered it. Yet, the sons of Khashoggi announced during Ramadan that they forgave their father’s killers, which would be decisive in sparing the killers’ lives.

In authoritarian societies, where rights are routinely violated, we should be especially sceptical when clemency is extended to the strong for violations against the weak

In 2010, after the Egyptian Court of Cassation overturned the death sentences initially imposed on Moustafa and Sukkari and ordered a retrial, the Tamims agreed to drop their civil suit in Lebanon against Moustafa. It was reported that he paid the family the princely sum of $750m in exchange. Upon retrial, their punishments were reduced to life imprisonment for Sukkari and 15 years for Moustafa. Sukkari and Moustafa, then, were the double recipients of clemency: first from the victim’s family, and then from Sisi.

Forgiveness is undoubtedly virtuous in certain circumstances, but because the strong can naturally use their power to extort forgiveness from those weaker than them, "forgiveness" may amount to nothing more than bitter concession to the perpetrator’s impunity.

In authoritarian societies, where rights are routinely violated, we should be especially sceptical when clemency is extended to the strong for violations against the weak. Without a strong and effective legal system that defends the rights of all, we should not be surprised to see the weak routinely professing forgiveness of their oppressors.

Weighty values

The law mitigates the natural advantage of the strong by vesting in the victims the right to prosecute those who violate their rights. Islamic law seeks to reconcile the values of justice, mercy and forgiveness by permitting, and even encouraging, the next of kin in murder cases to spare the life of the killer, but only after giving the next of kin clear authority to seek full justice.

Yet, even in Islamic law, the value of justice is sometimes deemed too weighty to permit the private virtues of mercy and forgiveness to prevail. For many Muslim jurists, the next of kin in a cold-blooded murder case do not have the authority to absolve a defendant of punishment by forgiving him, as they might in ordinary homicide cases.

It is not surprising that many Muslim jurists make this distinction. There is a difference between an incident in which a quarrel gets out of hand, leading to the victim’s death, as compared with the depravity of a defendant who with premeditation plans a killing down to its gruesome details, lures his unsuspecting victim, and plots his escape. All of these elements were present in the murders of Tamim and Khashoggi.

It would be bad enough in such cases if the guilty parties escaped punishment simply because of their positions. It is much worse when the law is used to achieve illegal ends.

In the case of Moustafa and Sukkari, the timing of the settlement with the family suggests a potential link with the reduced sentences they received upon retrial, even if the private settlement played no formal role. The fact that Sisi gave them the additional benefit of a reduced punishment reinforces the notion that the strong in Egypt are above the law.

Picking and choosing

Meanwhile, the absolution of Khashoggi’s killers under the guise of “forgiveness” is even more devastating for the rule of law in Saudi Arabia.

The Saudi Ministry of Justice and the Saudi high court had on prior occasions stated that in cases of cold-blooded murder the next of kin’s forgiveness of the guilty party is legally irrelevant. Yet, in this case, the government is contradicting its long-standing understanding of its own law in order to extricate the crown prince and his cronies from criminal responsibility for the killing of Khashoggi.

This makes the next of kin’s "forgiveness" look like little more than a sham, even if Saudi authorities can rightly point to authoritative opinions within the Hanbali school of law - which as a general matter is applied in the kingdom - that do allow the next of kin in a cold-blooded murder case to forgive the guilty party.

Picking and choosing among different legal opinions in a self-serving manner, particularly to advantage the strong and oppress the weak, however, has long been condemned as a ruse used by the unjust.

As the 13th-century Egyptian Maliki jurist Shihab al-Din al-Qarafi wrote:

“It is not appropriate for the mufti, in cases where there are two opinions, one of which is stern and the other lenient, to provide the stern response to the common folk while providing the lenient response to the elite who constitute the political class. That is almost the essence of immorality, betrayal of true religion, manipulation of the Muslims, [and] proof that his heart is empty of reverence for God.”

The arbitrary acts of clemency in Egypt and Saudi Arabia reveal the moral bankruptcy of these regimes, and make a mockery of their claims of modernisation and “moderation”. Their abuse of the ideals of clemency and forgiveness, moreover, contributes to the destruction of the moral resources necessary to preserve any decent society - and that is not forgivable.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.