How the West helped remove Islam's tradition of limiting state tyranny

Political scientists and media commentators have long pored over the question of why authoritarianism is a feature of Muslim societies, suggesting that Islam, however defined, is inherently given to tyranny and intolerance.

The argument has always been specious in that authoritarianism has been a feature of most parts of the world, with nothing restricting it to Muslims - as well as being a variation on the humble brag, in that it perpetuates the familiar discourse of the West as the world’s model for progress.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, there was intense western pressure to roll back ulama influence

But it also misses a point that has been obvious to some historians of the Global South for some time: that the hasty destruction of the Islamic juridical system under western imperial pressure contributed as much as anything else to the creation of despotic regimes that plague the Middle East region to this day.

Contrary to the popular view, Islamic religious authorities for centuries served as a check on the power of rulers, be they sultan, khedive or dey. This protective function performed by the ulama as judges, muftis and preachers was a distinctive feature of the Islamic model of governance, in which the ruler was left “sitting on top of society”, as authors Patricia Crone and Martin Hinds put it in God’s Caliph.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, there was intense western pressure to roll back ulama influence on the basis of the Enlightenment theory that everything deemed to be religious must be banished from the public sphere. The domain of sharia courts steadily shrank, and the educational and other prerogatives of the ulama were rolled back, except in outliers like Saudi Arabia.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Filling a vacuum

But the power of the political rulers who controlled armies and taxation only expanded - not only through this de-Islamification of society, but via the new forum for negotiating relations with various social classes: parliament. Constitutional assemblies of various forms and lifetimes began in Tunis in 1861, Istanbul in 1876 and Cairo in 1923, and while at first they were seen as a threat, ruling elites soon worked out how to manipulate them.

Mounting ineffective challenges to this transformation, the ulama and their supporters rarely found the time to step back and theorise about what was happening to the shape of the state through modernity’s dismantling of the Islamic system.

One such rare case is that of Mustafa Sabri, the Ottoman grand mufti who fled Turkey in 1922 after failing to stem the rise of secular nationalism following the Young Turk revolution of 1908, but who spent his last decades observing the advance of the same ideas in Egypt, his place of exile.

Writing in the 1940s, Sabri said that Muslim governments wanted to free themselves from the Islamic justice system and ulama supervision simply to impose their writ with only the superficial restrictions of parliamentary democracy. The result, he predicted, would be militaristic regimes of surveillance in which “religion and everything else is under the absolute authority of the government”.

Sabri argued that while European positive law was an evolving corpus that changed according to social and economic conditions, in Muslim societies, its imposition - filling the vacuum left by the dethroning of the Islamic system - was only one more lever in the hands of tyrannical rulers.

Sabri’s critique, first published in 1943 and then again in 1949, came at a time when the phenomenon of military castes seizing power through coups was just taking off, first in Syria in 1949, Egypt in 1952 and Turkey in 1960.

Repressive systems

German political theorist Carl Schmitt also wrestled with the predicament of the modern state after the historical downsizing of religious and monarchical power. During the Weimar period, he argued in Politische Theologie and other works that German constitutional democracy was so weak that figures acting in the name of the state were bound to step in, claiming exceptional powers to save it from collapse.

Exceptional power has been a feature of the Middle East political arena since the decolonisation period, reducing elected assemblies to rubber-stamp bodies. Egypt has used emergency laws to formalise the massive security powers of the state for most of the period since 1958, while Turkey’s system of military tutelage frequently overthrew elected governments until it was subverted by the AKP under leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan, when he was still the darling of the western commentariat.

Western entanglement with many of these authoritarian regimes has become even more sinister in recent years

Rather than the ad hoc condemnation of dictatorships and police states from the likes of Thomas Friedman in western media, any close historical analysis needs to focus on the speedy dispatch of one system and its replacement with another in the shadow of European power.

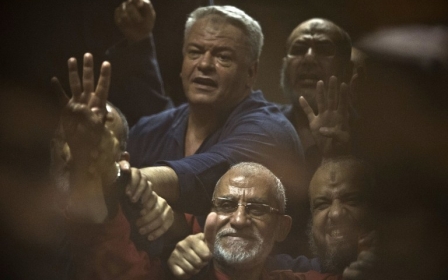

Western entanglement with many of these authoritarian regimes has become even more sinister in recent years. The Arab Spring uprisings were initially a grassroots movement to rectify the deformed states that governed with such brutality over millions of people, but now, draconian laws and surveillance technologies have created in the Middle East arguably the most repressive countries in the world.

In these Frankenstein polities, the living embodiment of the Panopticon of 18th-century social theorist Jeremy Bentham, the motto for survival at this stage is just to keep quiet and consume - and to leave the western commentators to spin their schtick on the lost hope for a Muslim democracy.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.