Stories of Palestine: Humanity in the face of an unjust world

Where does one begin when it comes to Palestine? A 74-year-old injustice, if we start counting from the 1948 Nakba, and more than a century old if we start from the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement and British-French colonisation of the region. The latter is a more sensible calculation, as these historical events laid the groundwork for the tragedies that followed, enabling and strengthening the colonial presence.

The tragedy of Palestinians leaves one speechless, as we find ourselves in an obvious violation of humanity, should the principles of justice and conscience be applied. But our world is one of power, double standards and fraudulent narratives, all aggravated by the grotesque claim of the invaders to a “civilised” nature, along with endless sermons on liberty, democracy and human rights - turning these concepts into propaganda devoid of meaning.

Palestine is part of that 'other world'. It is a tragedy obvious yet concealed, loud yet silenced - a travesty often described as a 'complicated issue'

The world does not consist only of Europe and the United States. While both regions have enjoyed relative tranquility, peace and prosperity since the Second World War, maintaining their equilibrium through “humanitarian” bills and “international” laws, and a privileged global economic status, the same circumstances have not been extended to the rest of world, which has been left to languish under various forms of enslavement, oppression, foreign intervention and war.

The underlying meaning and implication of terms such as “superpowers” necessitates the existence of “lesser entities” in the sphere of the former’s control, not only within a political-economic-military framework, but also in the context of media, culture, language and narrative. Thus, the show of power is not confined to violence, but can be expressed in the form of imagined narratives.

Palestine is part of that “other world”. It is a tragedy obvious yet concealed, loud yet silenced - a travesty often described as a “complicated issue”. This reductive phrase gives a free pass to those who refuse to take a stand on an outrageously straightforward matter: that of a nationalist movement that evolved in Europe, founded itself on a religious mythos, and, within the context of British and French colonisation of the Arab world after the First World War, began to ethnically cleanse an entire region, destroying the local people, history and memories, and establishing through terrorism and war a colony atop the rubble.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Estranged from home

Palestinians cannot be blamed for European racism and antisemitism, which developed, grew and continue to exist in the backyard of the “beacon of civilisation”. Jewish Arab and Sephardi communities remained robust until the foundation of Israel, thriving at times when some of their members gained prominence in fields such as literature, politics, philosophy and trade.

Whereas Jews in Europe faced persecution for centuries, Jewish Arab communities enjoyed relative stability until the Zionist movement estranged them from their home communities in Yemen, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, thrusting them into a deep perplexity. Moroccan Jewish poet Sami Shalom Chetrit, who journeyed into and out of Israel, captures this with great sensitivity in a letter to Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish titled “A Mural With No Wall”:

I have no such homeland, neither in writing nor on earth

But do not pity me - that’s not it. When it comes down to it, I am the murderer

And a thousand petitions against the occupation won’t help me, I am the soldier

Who kills three pigeons again and again with a single shot

And it is a matter of habit -

It was me who shot the forsaken horse, alone beside the house that became my new home

And I who sealed its windows well against the keening of the yearning mourners

And I who sealed the well with armoured concrete

That I should not see nor hear life from within the water

…

I am a jailor-poet, do not believe a word I say,

I am the jailor of myself and of my words

Whose wings are clipped, and of my sleep that wanders,

With no exact address to rest within

Israel, this “city on a hill” east of the Mediterranean, did not emerge from a vacuum. It is merely a continuation of a bloody European colonial lineage that has wreaked havoc on the world. Its disastrous remnants echo to this day, manifesting in the refugee crisis on the Mediterranean, in the bodies swallowed by the sea and freezing to death behind fences exclusively welcoming “blue-eyed blondes”, those who “look like us”.

This racism was once a dormant beast, sleeping to the far right and witnessed in “individual” acts of lethal police violence against Blacks; but today, in the “civilised” 21st century, it expresses itself in the mainstream.

Colonial atrocities

The Palestine of today is the America of yesterday, where the Promised Land was barren and feral, waiting to be inhabited, its indigenous people reduced to elements of nature, monsters, shadows or ghosts. All the atrocities committed by white Zionist colonisers are written into Europe’s colonial past, and understood, accepted and normalised as such.

As is typical with Europe’s colonial history, its aftermath has been ignored - and even celebrated. This was most evident in Britain’s official celebration of the Balfour Declaration centenary - a declaration that has brought havoc, murder and displacement upon Palestinians.

In her speech at a dinner marking the centenary, then-Prime Minister Theresa May said Britain was “proud of our pioneering role in the creation of the state of Israel”, without the slightest reference to how Britain’s illegitimate colonial entitlement to rights that are not its own has greatly affected the destiny of many helpless people, destroying their lives. Palestinians, like their indigenous kin in European colonies, do not exist in colonial eyes, with no value or regard given to their strife or very existence.

Palestinians, like their indigenous kin in European colonies, do not exist in colonial eyes, with no value given to their strife or very existence

The “white man’s burden” is thus true and real. It is the burden of a history filled with murder and slavery, evidenced by the economically and culturally prosperous capitals of the Global North brimming with the blood and tears of the Global South, whose people have been left to rot - negligible byproducts of the battle for civilisation on lands looted, burned, shackled and encrusted with military bases, nuclear waste and impeded development.

Discourse on Palestine is a discourse on the history of white European colonialism and its consequences on its ex-colonies, as well as on the history of the invisible indigenous communities kidnapped and trampled upon for the sake of building western “civilisation”. Israel was born of that history and embraced its own independent settler-colonial project after 1948, one that remains active and effective in the 21st century as a result of - and here lies the tragedy and hope - the continuous indigenous resistance of generations who refuse to let their land go.

Were it not for that resistance, settler-colonialism in Palestine would have become a forgotten blemish on the face of a humanity that has shamefully come to terms with previous settler-colonial atrocities.

Classism and racism

Palestinians today are the sum of a long history in which they have partaken since the dawn of “civilisation” in Mesopotamia, the Levant and ancient Egypt, up to this very day. They are, like the rest of us, a result of extensive and collective human history. The diverse Palestinian existence of Muslims, Christians, Druze, Bahais, Jews and Kurds, among others, exposes the true scandal of Israel’s exclusionary nature, derived from white eurocentrism.

Classism and racism are key features of modern-day Israel; on top of the racial pyramid sit the Ashkenazi, white European Jews. They are followed by Arab Jews and those of “Oriental” backgrounds, and in the lowest ranks are Black African Jews.

Indigenous populations have been invisible ever since colonisers declared they were taking over a “land without a people, for a people without a land”. That is why the “landless people” have been actively eradicating this diverse, rich existence, in favour of their own exclusivist narrative.

This and countless other examples can be added to a huge pile of evidence disproving colonial claims about the founding of “civilisation”.

Literary creativity reveals a deep and entrenched steadfastness, survival and persistence - a historic accumulation of language, culture, society and literature, denying borders, boundaries, dividers, and religious, cultural and historical fences. Residents of Palestine, before colonisers arrived and forged the borders of “nation states” - later abandoning them, weak and dependent - are part of the fabric of the “Middle East”, named as such by Europeans with centralised views, as it falls east of their central continent but closer to them than the “Far East”.

Literature is proof of a life ongoing; a hand from the past, writing in the present, for the sake of the future. The activity of the oppressed is not restricted to political life, but manifests more deeply through innovation and creative writing. These perceived ghosts and savages exist in action and in practice, within historical happenings that connect them to human continuity, the base and essence of all art.

One hand touches another, and another, until all hands merge into one; for art, like justice, is a true universal value. It is open to all, a road that has called to many from outside of Palestine: activists such as Rachel Corrie, Tom Hurndall, Roger Waters and Susan Sarandon, and even to those who have shed the shackles of colonialism, such as Yoav Bar, Felicia Langer, Ariella Aisha Azoulay and others.

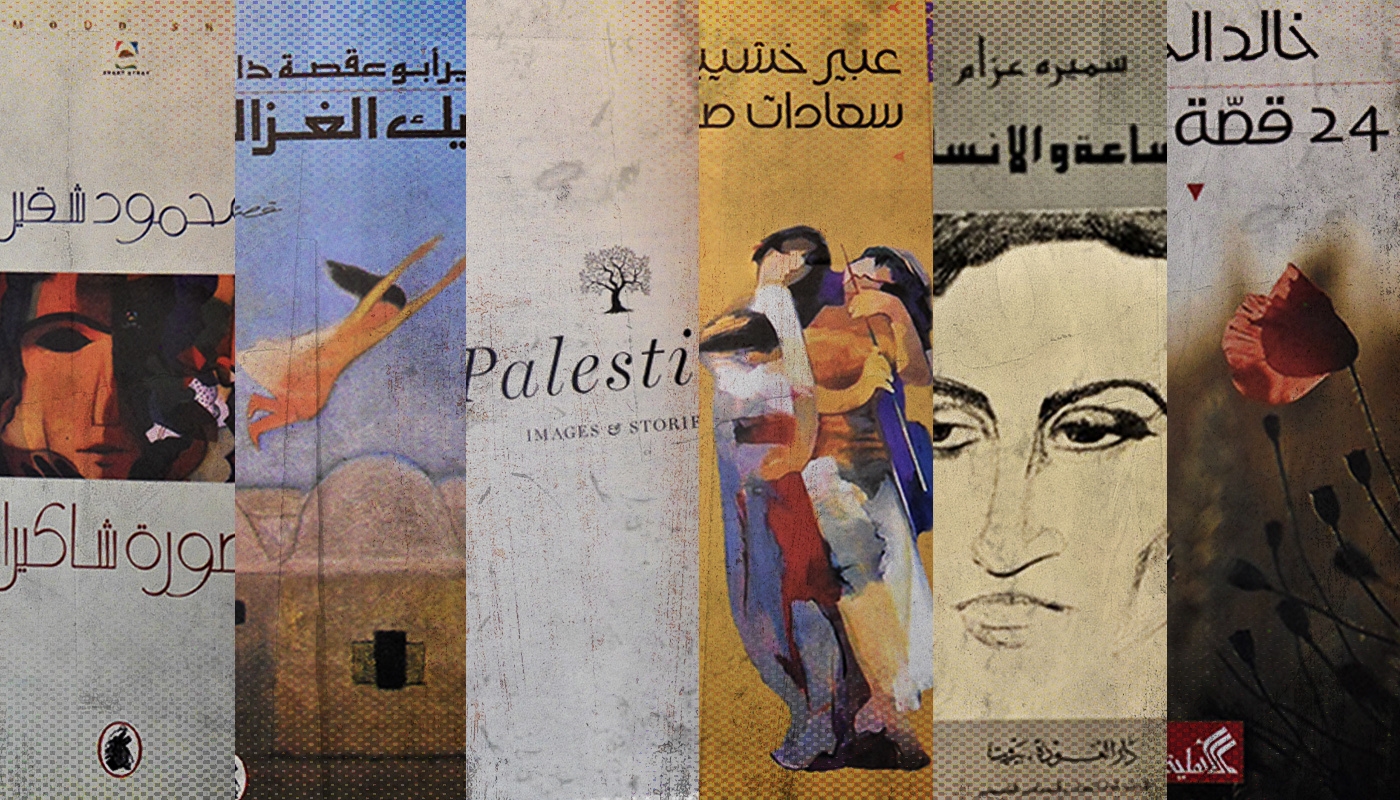

Stories of Palestine

Last year, I curated a special portfolio of short stories from Palestine for the Amherst College-based literary journal The Common. At the heart of this portfolio lies humanity and human contact, enveloped in delicate stories about the reality as it exists today: colonised areas of 1948 with their few remaining indigenous communities, who are seen as “minorities” on their own land; other areas undergoing an active occupation or suffocating siege, known as “the West Bank and Gaza”; and forcibly displaced Palestinians and refugees in all corners of the Earth, denied their right of return.

Samira Azzam’s story takes place in Iraq, where the author lived and worked as a teacher for part of her life after being displaced from her city, Akka, in the year of the Nakba. In her story there is an implicit, singular connection between the interwoven threads of colonialism in the Arab region, and power dynamics accompanied by misinformation.

The stories of Abeer Khshiboon, who lives in Berlin, and Suhail Matar, who lives in the US, exemplify the weighty effects of colonialism on Palestinians who have remained living on their own land, now dubbed Israel, at the heart of the colonial project.

Khshiboon’s story takes place in Amman and recounts a meeting between a ’48 Palestinian (a term that refers to the Palestinians who remained in Israeli-colonised land after the Nakba in 1948) and a Syrian during a concert of the Lebanese singer Fairouz. Looking at their passports, the protagonists are nationals of two entities in a state of war - but deep inside, they belong to one extended community, naturally united and refusing the erasure brought on by artificial borders. The story simply and organically recollects the daily practices of human unification in a region politically divided through colonialism.

Matar’s story describes another “forbidden” meeting of a '48 Palestinian and a Palestinian from Gaza - a meeting that can only take place in another country. While Khshiboon’s protagonists are brought together by joy, Matar’s are united by sorrow and a deep feeling of tragedy, thus fulfilling the cycle of shared circumstance and common human destiny.

Meanwhile, the stories by Khaled al-Jebour and Ziad Khaddash delve into problematic aspects of the daily lives of the colonised. Jebour’s text tells the story of Palestinian workers who are smuggled into Israel, to their occupied lands, to illegally construct Israeli settlements; they go into hiding every day in the basement and are eventually caught by a special Israeli unit that hunts down unauthorised workers.

Is this a narrative of stark contradiction and complex, surrealist structure? No; it is merely the daily lived reality of many Palestinian workers caught between the hammer of Israeli colonialism and the anvil of poverty and unemployment, the latter a direct result of the former.

Khaddash’s short texts increase the paradoxical complexity, exposing the implicit humiliation in a “peace” process that has turned the “Palestinian Authority” into a tool at the hands of the occupation - or, at best, a mere helpless observer to the occupation’s crimes. Another searches for a solution to a tragic problem: what to do about a student who flinches in pain every time he laughs, because of the burn scars he got in Israel’s shelling of Gaza?

Art and humanity

Izzat al-Ghazzawi’s story points to another tragedy among the many that Palestinians suffer through: detention in the occupation’s prisons, where more than 4,400 prisoners are held today, including 160 children. The protagonists are women, who play a heroic, central and active role in Palestine. This aspect is also reflected through Suheir Abu Oksa Daoud’s story and her heroines, wherein rainwater plays a vital role; and in Khaddash’s texts, with women portrayed as deeply rooted olive trees.

Mahmoud Shukair’s story calls attention to the failing role of the United Nations, controlled by the interests of superpowers and their vetoes in the Security Council when dealing with the plight of Palestinians. And Eyad Barghuthy’s story displays an intense struggle with the coloniser, expanding beyond the spatial sphere and into the temporal, as the celebration of Ramadan turns into an occasion for tyranny and land confiscation, alongside subtle allusions to differing human temperaments united by oppression and moving towards solidarity.

Finally, Sheikha Hussein Helawy’s story completes the circle of human existence through the tale of a woman trapped in a coma while her mind roams freely, observing the immediate world: the television, the curtains, the nurses, and the diminishing number of visitors. The mundane realities of a small hospital room morph into a changing and transforming world, with no room for deviation off course - inadvertently summarising Palestine’s bleak horizon in an unjust world governed by power dynamics.

Palestine might not exist on the political map of the world, in UN resolutions, or in the future plans of hypocritical superpowers - but it can be found in all of those who celebrate justice and equality as high universal human values and seek to achieve them.

It can be found in the child facing the coloniser’s tanks, rock in hand, called a “terrorist” by the “civilised” world; and in the persistence of Palestinians bound to humanity through art and literature, as expressed by the great Darwish: “Don’t ask the trees for their names / Don’t ask the valleys who their mother is / From my forehead bursts the sword of light / And from my hand springs the water of the river / All the hearts of the people are my identity / So take away my passport.”

This is Palestine as expressed in its rich, diverse literature. Welcome to Palestine.

This piece has been translated from Arabic by Nour Jaljuli.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.