In the Middle East our very memory of the world is through poetry

Does poetry need justification - definition, or a particular month of the year to mark and perhaps even celebrate it? April is evidently National Poetry Month in the United States.

Poetry is its own philosophy, its own justification, Azharo min ash-Shams, as we say in Arabic, brighter and more evident than the sun!

On this occasion the New York Times published a delightful piece in which Elisa Gabbert asks a very basic but poignant question: “What is poetry anyway?"

The answers, if anything, are, well, poetic: "The poem is a vessel," she writes; "poetry is liquid." I immediately remembered a poem by Ahmad Shamlou, perhaps the greatest lyricist of modern Persian poetry, where he writes:

I became a fruit on a tree,

And I became a stone in a child’s hand -

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Only a miracle can save me from myself -

Deadest as I am against myself!

Designation of a particular month, April or October or any other month on any calendar, or a day, a year, for poetry is a very strange proposition to my Persian ears. We dwell in the world poetically, as the German philosopher Martin Heidegger might have said. Someone once said what Muslims do is not memorising the Qur’an but Qur’anifying the memory.

Very true. In the same vein, our very memory of the world is poetic. Marking a particular month for doing poetry is a bizarre demarcation to take time from the regimented logic of capitalist modernity for the encapsulation of life in digestible pieces. Poetry does (should do) precisely the opposite of that.

Poetry for us needs as much a particular month as it does any dictionary definition, or a deep philosophical explanation, or some moral justification. Poetry is its own philosophy, its own justification, Azharo min ash-Shams, as we say in Arabic, brighter and more evident than the sun!

A destitute time

"What are the poets for in a destitute time?" Heidegger famously cites from Friedrich Holderlin’s poem "Bread and Wine", in an essay originally published in German in 1936. Neither Heidegger’s Nazi affiliations nor indeed Holderlin’s specific German provenance may leave room to ask the same question in other contexts - but still the issue remains: what is the point of poetry in the time of Donald Trump, or Vladimir Putin, or Bashar al-Assad, or Mohammad bin Salman, or the terrors visited upon Afghanistan, Syria, Palestine, Ukraine, or Yemen?

What is the point of poetry in the time of Trump, or Putin, or Bashar al-Asad, or Mohammad bin Salman, or the terrors visited upon Afghanistan, Syria, Palestine, Ukraine, or Yemen?

Trump, you may object? Isn’t his time over and done with? Obviously you don’t live in the US if this objection occurs to you.

The time of Trump was not over when, after an attempted electoral coup, he reluctantly left office - anymore than the time of Putin is over in Ukraine, or any other thug visiting vengeance on Palestine, Syria, Afghanistan, or Yemen.

In the US, as the most violent imperial force around the globe, the time of Trump and - after him - the era of Trumpism, has just begun. The man has tapped on and unleashed a violent subterranean force not publicly admitted since the American Civil War and all its racist white supremacist underpinnings.

What marks the epicentre of American Trumpism (there are plenty European versions of it too) is in fact a poem.

During the inauguration of President Biden, suddenly the name of a young poet, Amanda Gorman (born 1998), was catapulted to global fame. Her inauguration poem, "The Hill We Climb", was read and heard like a soothing shower of absolution after the vile and ugly presidency of Donald Trump.

When day comes we ask ourselves,

where can we find light in this never-ending shade?

The loss we carry,

a sea we must wade.

We've braved the belly of the beast,

We've learned that quiet isn't always peace,

and the norms and notions

of what just is

isn't always just-ice.

But before we knew it, the poet was the subject of the worst celebrity culture, was brought “to perform at the Super Bowl” and featured on Vogue and that was the end of her as a poet.

I have always considered the German philosopher Theodor Adorno’s famous phrase - "To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric" - at once painful and false. Pain of a people, and the obscenity of an injustice perpetrated on them is the purest and most real wellspring of their poetry - their defiance of that calamity and continuing to live their best poem.

"One day," I read in a photographed graffiti from war-torn Syria, "this war will be over and I go back to my poetry." The picture was of a bombed and destroyed street. The war was not over - and this line itself was a precious piece of poetry.

Traumatic moments

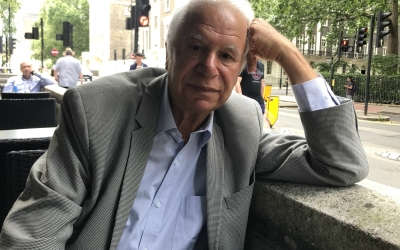

In both public events and private gatherings, I have seen two major poets, Ahmad Shamlou and Mahmoud Darwish read and recite their poetries. They were not performances. They were epics.

In the wake of the Iranian revolution of 1977-1979, a famous “Ten Night” of poetry recitation and speeches inaugurated the cataclysmic events that led to the downfall of the Pahlavis and the success of the revolution.

One of the first atrocities the revolutionaries perpetrated was to execute a poet, Said Soltanpour, for his political beliefs. The Shah before them had done the same, having a revolutionary poet, Khosrow Golsorkhi, executed.

In the most traumatic moments of a national crisis or uprising, poetry has remained definitive to multiple nations and cultures.

My generation was born and raised on a constellation of iconic poets who defined not just the fate of their own homelands but brought the best of those nations to global attention.

Who were these poets and why did they matter? Vladimir Mayakovsky from Russia, Pablo Neruda from Chile and by extension Latin America; Faiz Ahmad Faiz from Pakistan and by extension the entirety of the subcontinent; Nazim Hikmet from Turkey; Mahmoud Darwish from Palestine and by extension the entirety of the Arab world; Langston Hughes from the US, and by extension the entire history of tyrannised African Americans in the western hemisphere: they all came to enable us to understand our own national poet Ahmad Shamlou better.

When anyone of them recited a poem it is as if it was for all of them - as in this famous poem of Langston Hughes:

I am a Negro:

Black as the night is black,

Black like the depths of my Africa.

I’ve been a slave:

Caesar told me to keep his door-steps clean.

I brushed the boots of Washington.

I’ve been a worker:

Under my hand the pyramids arose.

I made mortar for the Woolworth Building.

I’ve been a singer:

All the way from Africa to Georgia

I carried my sorrow songs.

I made ragtime.

I’ve been a victim:

The Belgians cut off my hands in the Congo.

They lynch me still in Mississippi.

I am a Negro:

Black as the night is black,

Black like the depths of my Africa.

How, you may wonder, does Darwish sound in Persian, or Shamlou in Arabic, or Mayakovsky in Turkish? I can only judge by how they all sounded in Persian, or now English, and how they enriched and emboldened our reading of a global scene which they had made meaningful to us.

We never thought of these poets exclusively in terms of their progressive politics - that was given but not definitive to how we read their poetries. WB Yeats, TS Eliot and Maya Angelou would later enter this pantheon.

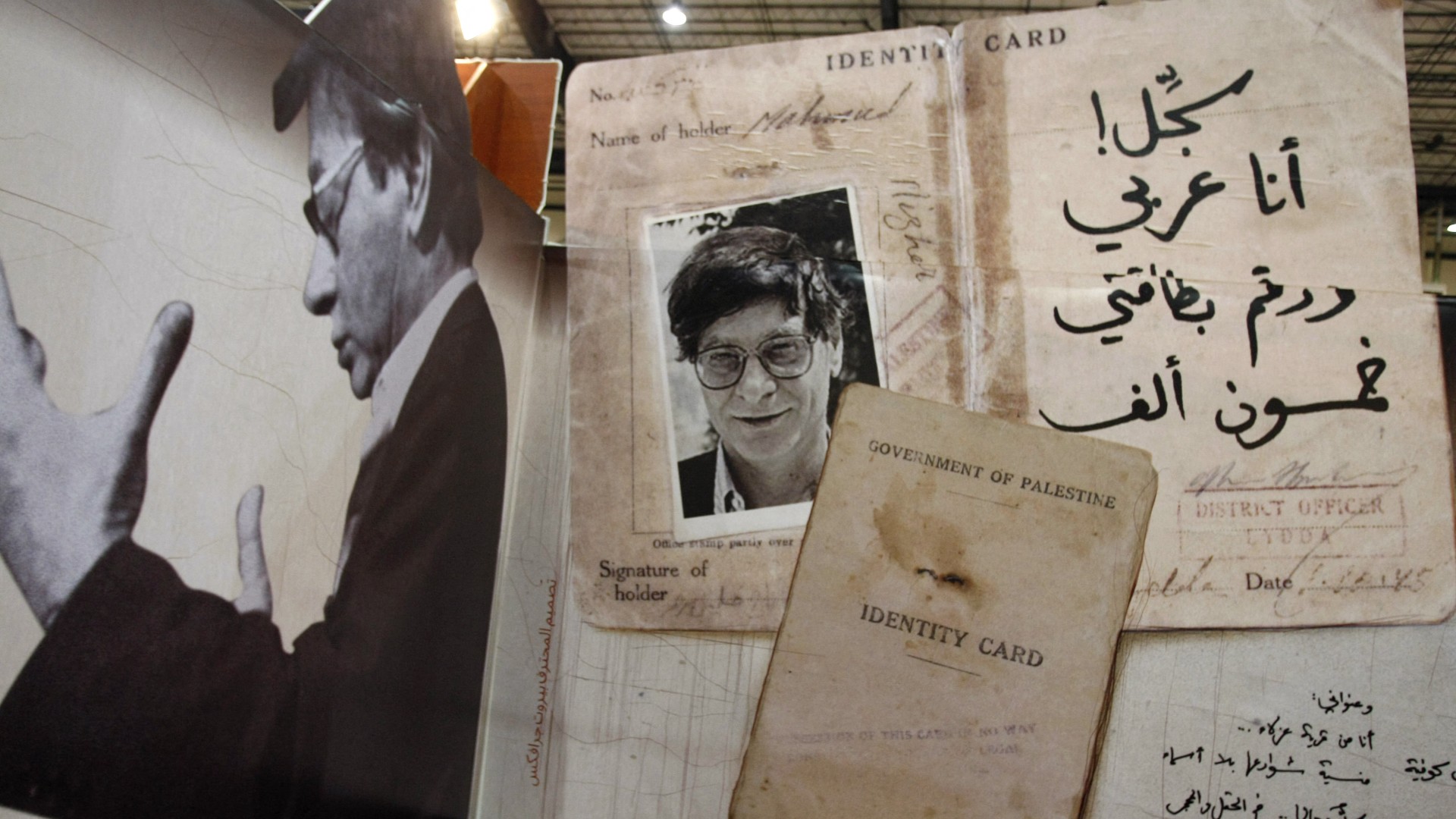

Their poetry was their politics, their politics their poetry. Take Mahmoud Darwish from the Palestinian cause. They would not know which way they are going - not just in the justice of their cause, but in the beauty of their vision.

سجل

Write down:

أنا عربــــــــــــــي

I am an Arab

ورقم بطاقتي خمســــــون ألف

And my ID number is 50,000

واطفالي ثمانيـــــــــــــــة

I got eight kids

وتاسعهم سيأتي بعد صيـــــف

And the ninth is due after the summer

فهل تغضـــــــــب؟

So will you be mad?

: سجل

Write down:

أنا عربــــــــــــــي

I am an Arab

These poets were our subterranean ways into the world and how people in our immediate and distant surroundings saw the world. When we read these poets not a single one of us had travelled outside Iran and throughout our lives may have never been able to read those poets in their own tongue.

For sure we lost much in translation but we also gained even more in precisely those translations.

In a famous part of his Masnavi, Rumi says:

Ey basa Hendu-o Turk-e hamzaban/

Ey basa do Turk chon biganegan/

How often it happens that a Hindu and a Turk understand each other/

And how often it happens that two Turks are like strangers to each other!

By virtue of the proximity of all these poets to each other in the hospitable Persian in which we read them, whatever we lost in translation we more than gained in a different dialogical positioning of these poets in the community of each other.

Years ago in Beirut, my dear late friend who recently passed away, Samah Idris, devoted a whole issue of his journal al-Adab to the Arabic translation of some seminal Persian poets. I remember I sat in a delightful restaurant with a Palestinian friend by the sea and we read the Arabic translations as I recited from heart the original Persians.

It was a strange and unchancy experience. Somewhere in the fresh breezes of the Mediterranean Sea the Persian and Arabic words were coming together to craft a tertiary space where poetry dwelled and defied their worldly habitat to intimate a world where poetry dwelled in pure undiluted form of breathing and feeling and being.

Our words between Persian and Arabic smelled of sea salt.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.