Boris Johnson must stand up to Sisi in defence of human rights

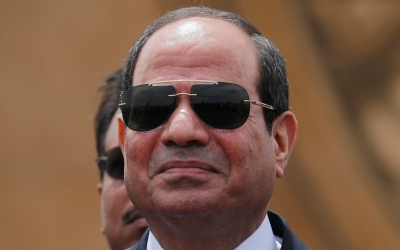

In September 2014, addressing the United Nations General Assembly for the first time as president of Egypt, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi swore to build “a new Egypt … a state that respects and enforces the rule of law [and] guarantees freedom of opinion for all”.

It has, to put it mildly, not worked out like that - but for six years now, Western leaders have played along, welcoming Sisi as a trading partner and ally, while expressing vague concerns about human rights abuses by his administration.

Suppressing dissent

Last April, as a US citizen convicted in a mass trial wasted away in an Egyptian prison - Moustafa Kassem, who died last week after a hunger strike - President Donald Trump praised the “great job” being done by Sisi.

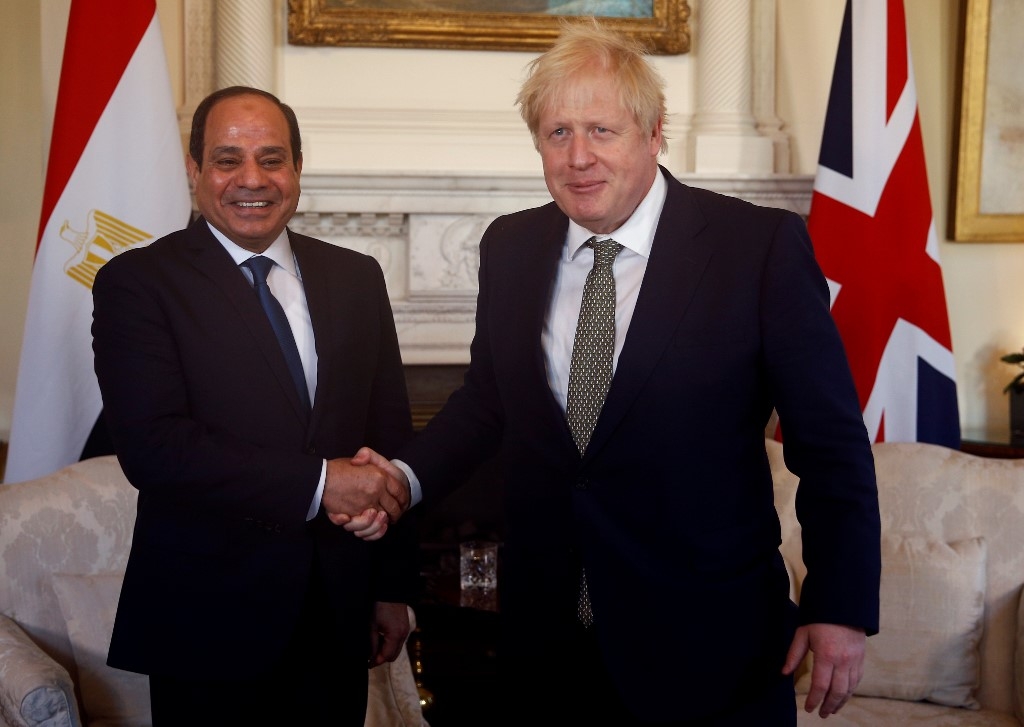

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson and other world leaders have shaken Sisi’s hand and been polite enough not to mention the enforced disappearances, torture and death sentences used to suppress dissent in Egypt.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Ammar was weak, filthy and broken, his eyesight permanently damaged from the beatings. He had not been allowed to bathe for four months

As Sisi touched down in London for the UK-Africa Investment Summit this week, Britain’s ambassador to Egypt extolled the “strong economic and political relations between the two countries”.

In the evening, Prince William welcomed the Egyptian president to Buckingham Palace, alongside other African heads of state. A bilateral meeting with the prime minister was also scheduled. The full red carpet, in short.

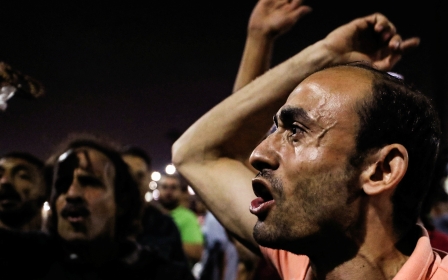

Meanwhile, a mass trial of 304 people, including several who were children at the time of their alleged offences and face potential death sentences, was reaching its conclusion in Cairo.

Reprieve’s Egypt Death Penalty Index found that around 2,500 people were sentenced to death in Egypt in the first five years of Sisi’s rule. A total of 1,884 of these preliminary death sentences were handed down in inherently unfair mass trials of 15 defendants or more.

Violating international law

It can be hard to picture these mass trials. Sisi’s Egypt is a black box, in which Western journalists operate under strict supervision and reporters critical of the regime are intimidated and arrested. While some images do emerge, showing groups of men in white prison uniforms locked in cages in the courtroom, independent reporting on trials is extremely difficult.

The sheer number of people involved can be hard to fathom: 529 defendants in one trial in Mattay and 683 in another in Minya, swept up under Egypt’s assembly law, which holds huge groups of people responsible for the actions of a few. Inevitably, children are caught in the net, detained and tried alongside adults - a grave violation of international law.

Speaking out is an act of great bravery in Egypt, and one fraught with risk. When the mother of one of the juvenile defendants currently on trial spoke with Reprieve’s caseworkers, she asked us not to publish her name. The story she told us was horrifying.

In December 2016, Ammar was getting ready for school when agents raided his home. He was 17. For the next four months, he was blindfolded and chained to a wall in a cell with 25 other prisoners at Egypt’s national security headquarters.

On his charge sheet, he was accused of joining a terrorist organisation and of criminal conspiracy to commit murder. There was not a shred of truth to these allegations. The real reason for his detention became appallingly clear when officers took him to a neighbouring cell where his father was being held.

Beatings and electric shocks

Ammar was stripped and hung from the ceiling. For three days, officers beat him and applied electric shocks to his genitals and his head, long after his father told them he would admit anything if only Ammar’s torture would cease.

When his mother was finally allowed to see him, she could hardly recognise her son, the promising student with beautiful handwriting who had memorised the Quran and wanted to study engineering at university. Ammar was weak, filthy and broken, his eyesight permanently damaged from the beatings. He had not been allowed to bathe for four months.

When Johnson sits down with Sisi this week, I urge him to raise Ammar’s case, rather than hide behind platitudes about building “a prosperous and democratic society” in Egypt.

Sisi says his regime should not be judged by “European standards”, but there is nothing European about the right to life, the right to freedom from torture or the right to a fair trial. These are universal human rights, and they are being violated every day in Egypt.

In principle, the UK government is opposed to capital punishment in all circumstances. Face to face with a leader who uses death sentences to silence political opposition, the prime minister must show the moral courage to oppose it in practice, too.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.