Syria war: Will detente with Jordan bring Assad back into the Arab fold?

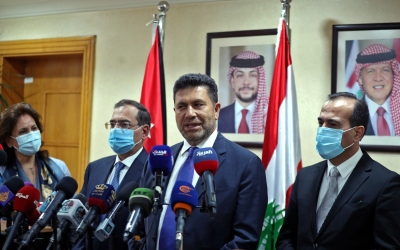

Jordan and Syria are officially friends again. After a decade of hostilities, prompted by King Abdullah II backing President Bashar al-Assad’s enemies in the Syrian civil war, the estranged neighbours recently announced a raft of measures to normalise relations.

The border will fully reopen to trade, and flights between the capitals will resume, as will security and water cooperation. Assad and Abdullah even spoke on the telephone for the first time in a decade. The king has also lobbied his ally, US President Joe Biden, to ease pressure on Damascus - quite the departure from a few years ago, when Jordan hosted American-armed Syrian rebels.

Both governments were conscious of the two countries' historical interdependence and wary of irreparably damaging the relationship

Yet, this reconciliation is unsurprising. Detente serves both leaders’ domestic and international agendas, and the warming of ties is driven primarily by pragmatism. This conforms to the historical pattern of Jordanian-Syrian ties. They may fluctuate between enmity and friendship every few years - often due to global and regional politics - but given the importance of these neighbours to each other, realism invariably triumphs and amends are made.

Jordan’s opposition to Assad was lukewarm at best. Unlike many Arab leaders, Abdullah never closed his embassy in Damascus, although staff numbers were cut. Jordan hosted the Military Operations Center, which facilitated the training and arming of moderate anti-Assad rebels, but it carefully controlled its border and did not allow rebels to come and go as they wished, unlike Turkey to Syria’s north. This contributed to the relative weakness of the southern rebels.

Similarly, Assad was careful in his hostility towards Jordan. Jordan was not as heavily criticised as some of Damascus’ other enemies, such as Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia and the US. Even at the height of Syria’s civil war, relations were not as strained as they might have been.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Political differences

It is likely that both governments were conscious of the two countries’ historical interdependence and wary of irreparably damaging the relationship. Historically, southern Syria has been more closely linked to northern Jordan than to northern Syria, being in the same Ottoman province.

Though British and French imperialists created separate countries, family and tribal ties straddled the border, particularly around the Hauran region. Indeed, early in Syria’s war, the first refugees were Hauranis crossing into Jordan to seek shelter with relatives. Such connections helped forge important trade links; southern Syria and northern Jordan are economically dependent on each other in different ways. In addition, Syria provides Jordan with access to the Mediterranean and overland routes to Europe, while Jordan offers Syria access to the Red Sea and overland routes to the Gulf.

Yet, despite this cultural and economic closeness, political differences have prompted tensions. Since 1963, Syria has been ruled by left-leaning, anti-western Baathist autocrats, seemingly the polar opposite of Jordan’s pro-western, capitalist Hashemite monarchy. They were on different sides of the Cold War and had different regional allies. In 1970, Syria even briefly invaded Jordan in support of Palestinian guerillas fighting a civil war with the Hashemites, while a decade later, Jordan was sponsoring Muslim Brotherhood militants trying to topple the Syrian Baathist regime.

In between these rounds of enmity came bouts of friendship, as the two states fought together against Israel in 1967 and 1973. Ties were then strained in the 1980s when they favoured opposite sides in the Iran-Iraq War, but warmed in the 1990s when both engaged with the Arab-Israeli peace process. They soured again in the mid-2000s when Jordan aligned with US attempts to diplomatically isolate Syria after its involvement in the 2005 assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, but warmed again a few years later when this isolation failed.

Throughout this stormy relationship, both governments have been willing to shift away from confrontation rapidly when their interests shifted. This has prompted the current reconciliation.

Influence over Damascus

For Jordan, it is clear that the campaign to oust Assad, to which it reluctantly signed up, has failed. Yet, unlike the other anti-Assad states that have lost interest, it is suffering the immediate effects of the conflict in the form of more than 650,000 Syrian refugees and a struggling economy.

Abdullah hopes that detente with Assad will open trade routes and create more stability in southern Syria, allowing some refugees to go home. By opening air links with Damascus and urging Washington to exempt Jordan from its harsh anti-Assad Caesar sanctions, which it recently did on a regional gas deal, Abdullah sees the financial benefits of Jordan becoming a conduit for outsiders dealing with Syria.

With Washington retreating, Jordan needs to find other ways of ensuring the peace and stability it craves

Moreover, geopolitically, Abdullah is adjusting to the shifting landscape. With Washington retreating, Jordan needs to find other ways of ensuring the peace and stability it craves, beyond relying on the former hegemon. Engaging Assad, it hopes, will allow it a degree of influence over Damascus, particularly on the presence of Iranian and Iran-aligned troops on its and Israel’s border, which could provoke an unwanted conflict.

Assad also clearly benefits. Full trade with Jordan and help bypassing the Caesar sanctions offer some reprieve to Syria’s flagging economy - although these measures are unlikely to have a transformative effect. More important are the geopolitical gains: Assad has not had to make any concessions to earn this rapprochement, so it serves to legitimise his cause.

Turbulent ties

Jordan is not alone in normalising ties with Syria, as Egypt also seeks to enhance links, and the UAE is leading a campaign to bring Damascus back into the Arab fold. Normalising relations with Jordan could be a stepping stone towards reconciliation with the wider Middle East, readmittance to the Arab League, and - Assad hopes, perhaps forlornly - much-needed reconstruction funds.

Detente, therefore, makes sense for now, but ties are more likely to be functional than friendly. The ideological differences between the regimes and a degree of mutual suspicion remain, as much as the deep structural reasons why they cannot stay estranged for too long.

It is highly likely that this current round of friendship will collapse into enmity whenever the next local or regional crisis pits Amman and Damascus against one another, but it is also likely that such hostilities will eventually subside, as they always do. Such is the cyclical nature of Jordan and Syria’s turbulent ties.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.