Lebanon: Is war coming?

Every year on 13 April, the outbreak of Lebanon's longest civil war (1975-1990) is commemorated with a flurry of writings, pronouncements, and the occasional public event.

At worst, worn-out cliches, like the need to preserve "civil peace" and the magic formula of "no victor and no vanquished," are invoked as a guarantor of co-existence. At best, apolitical accounts of the devastation of war are cited as a warning of its horrors lest it be repeated.

In both cases, the structural causes, political consequences and historical contingencies of war are obscured.

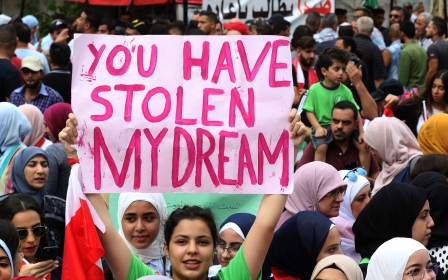

This year, commemorations were muffled. The country is facing unprecedented economic collapse and political paralysis. Social conflict is at an all-time high, and regional wars and geopolitical tensions are simmering.

This combination has historically been a recipe for war in Lebanon, so is war coming?

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Geopolitical considerations

So far, the prospects of an all-out armed conflict on the scale of what took place in 1975 are low. But civil wars don't have to be copycats of their predecessors. New conditions generate new forms of conflict.

Civil wars don't have to be copycats of their predecessors. New conditions generate new forms of conflict

In today's context, prolonged political instability and wide-scale impoverishment will offer a fertile ground for violent confrontation if regional and international factors become favourable.

Unlike 1975, there is no organised political movement carrying a progressive project of radical political and economic reform, so any confrontation will not hold the prospects of positive change. On the contrary, material need and social fragmentation divorced from class consciousness and political unity will fuel the cooptation of large social segments of the population for destructive ends. With inflows of capital further drying up, finance for war may become a welcome alternative.

In short, geopolitical considerations will trump domestic demands.

In Lebanon, geopolitical considerations are at present determined by foreign actors agitating for instability. These are the US, Israel, and Saudi Arabia. None is concerned about reforming Lebanon's political economy or system, except in as much as it impacts the only item on their agenda: Hezbollah's armed resistance to Israel and its regional interventions in Syria and Yemen against their axis.

Riding the wave of blaming Hezbollah for all the financial and political ills of Lebanon, aside from being false, is either naive, superficial, or a sinister attempt to instrumentalise the just demands for change in order to fuel regional confrontation and bring it to bear more directly on the Lebanese front.

The scope and shape of this confrontation on this front will be determined by the military balance of power and the rising role of diplomatic and economic warfare.

Military confrontation limits

Hezbollah is the most powerful armed group in Lebanon. It is the most highly organised, equipped, disciplined, sophisticated, and tried fighting force. Its interest in preserving the status quo has kept any large-scale fighting at bay. However, Hezbollah's ability to monopolise the start and outcome of a civil war is as exaggerated as its role in the current crisis.

Firstly, all factions in Lebanon harbour weapons, and, if foreign funding is offered, they can quickly restock. To compensate for Hezbollah's strength, a head-on confrontation may be replaced by undercover bombings or a street war of attrition, where Hezbollah's experience is not as effective.

The Lebanese army's role will also be crucial. The western media's obsession with, and antagonism towards, Hezbollah and Iran has meant that there is little coverage of US funding and support of the Lebanese army.

Since 2006, the US has provided over $1.7bn to the Lebanese army. In order to protect Israel, this aid is designed for internal security and its ideology is being altered to emphasise terrorism rather than Israel as the main threat. In other words, it's being fitted more for civil strife than foreign defence.

Despite these efforts, the army remains a lesser military foe. But military dominance is not sufficient to win a war. This brings us to the second, and perhaps more important factor limiting Hezbollah's role. Hezbollah may have the gun power to swiftly defeat internal paramilitary groups and opponents in the army, but holding ground is another business. Sectarian logic will prevent it from securing territory outside its current strongholds without willing allies among other sects.

If the army intervenes, it will not retain full loyalty to its leadership and will split along sectarian lines. Militarily, this is to Hezbollah's advantage. But internal divisions along sectarian lines will increase, not decrease, security threats.

Last but not least, all intense episodes of the Lebanese civil war involved direct foreign military intervention. Today, the main party capable - and willing - is Israel. However, the costs of ground intervention are much higher than in the past, thanks to a long history of resistance culminating with its most advanced incarnation, Hezbollah.

In an ironic twist of history, other Arab countries, like Iraq and Syria, have become more susceptible as sites for settling scores between the US-led axis and its opponents than Lebanon. The uncertainties, or riskiness, of these military scenarios in Lebanon have fuelled war by other means, namely diplomatic and financial.

Diplomatic and financial warfare

International diplomacy has been a persistent tool of undermining Hezbollah, particularly since the 2005 assassination of prime minister Rafik Hariri. The kangaroo court set up to investigate his killing and blame Hezbollah is a case in point.

Currently, efforts to internationalise the crisis are spearheaded by the Maronite Patriarch Bechara Boutros al-Rai, a defender of the political and financial system. He is calling for "active neutralism".

US banking sanctions, aimed at drying Hezbollah funding, have harmed US traditional allies through collective punishment

Traditionally, this was the discourse of the right-wing forces. It has always meant preservation of western hegemony and dissociation from the struggle with Israel. But in the melee of today's devastating and confusing regional wars, and due to Hezbollah's overzealous defence of Lebanon's political system against the uprising, and a growing regional push for further normalisation with Israel, this right-wing discourse has gained wider currency.

Local Lebanese and Arab media, as well as segments of civil society, have played a part in propping up al-Rai's proposal, partly. Many were driven by the agenda of their western and Gulf funders, which is a reminder of the pernicious - yet largely implicit - role of finance in the ongoing battle, including the other side of US aid: sanctions.

Contrary to claims by many supporters of Hezbollah and their allies, US sanctions on the banking sector are not the root cause of the current banking crisis. But they should not be ignored either. US banking sanctions, aimed at drying up the funding of Hezbollah, have exacerbated an already fragile system.

If anything, they have harmed US traditional allies through collective punishment, a grim reminder of the unreliability of the US as an ally. But these sanctions can also sow the seeds of future mayhem, or in imperialist terms, creative destruction. The impact of these sanctions is amplified by two factors: the refusal of Gulf states to pump any of their trillion dollars worth of surplus capital, and the sabotage, through local allies, of attempts to turn eastward or even seek economic support from other Arab countries like Iraq.

Just demands

None of the above absolves Hezbollah, and more so its two allies, namely the Amal movement and the Free Patriotic movement, from their complicity in Lebanon's current debacle.

Nor does it relieve social forces who genuinely believe in radical change from forming a solid front with clear objectives and a trustworthy leadership capable of protecting the just demands of the uprising from being hijacked by local and international counter forces.

The recollection of past violence and anticipation of future violence has been a mainstay in the lives of ordinary Lebanese

But all of the above reaffirms the regional dimension of Lebanese politics. Local actors seeking change ignore it at their own peril.

With or without a civil war, failing to solve the crisis along socially just terms will lead to increased forms of violence, ranging from petty crime to organised mafia-style management of scarce resources under sectarian protection.

Until a resolution or a rupture occurs, war will remain, as anthropologist Sami Hermez put it, a "structural force of social life". After all, as Hermez adds, the recollection of past violence and anticipation of future violence have been a mainstay in the lives of ordinary people.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.